Michael Pascoe: Housing catastrophe worsens as Falinski failure exposed

Rising rents and tighter vacancy rates is creating even more pain for those who can least afford it, Michael Pascoe writes. Photo: TND

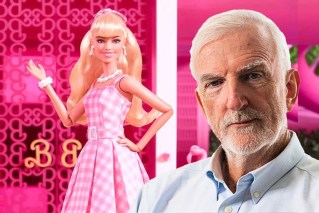

How badly did Jason Falinski maul and distort the housing inquiry he chaired at our expense? So badly the secretariat took their names off the final report.

In Parliament House public-servant-speak, that’s about as strong a condemnation as you can get short of a career-ending burning of the document in the forecourt.

In the various parliamentary committees’ reports, the secretariat – the people who do the mountain of work that goes into an inquiry and know the submissions better than anyone – are listed under “members” of the inquiry along with the politicians.

Not for Mr Falinski’s perversion of the process along the ideologically pre-judged lines he was chosen to deliver. The secretariat didn’t want to be associated with it.

The secretariat have avoided any association with Liberal MP Jason Falinski’s housing affordability inquiry.

I’m reporting their pointed silent protest as Australia’s housing catastrophe measurably worsens.

On Monday Alan Kohler explained what an economic and social disaster the housing market has become for Australia, undermining our future.

“Education and hard work no longer determine how wealthy you are; now it comes down to where you live and what sort of house you inherit,” he wrote.

And the rental market – the catastrophe – is worse and worsening.

Also on Monday, real estate website Domain released its March rental vacancy statistics – the worst since Domain started collecting the figures last century and another step down from the February data.

The further tightening of an already tight rental market predictably occurs as the international borders are opened for the workers, students and tourists the country seeks.

From a net migration loss of nearly 90,000 last financial year, last week’s budget is forecasting a net gain of 180,000 next year and an extra 213,000 needing somewhere to live in 2023-34.

Sydney and Melbourne vacancy rates have fallen sharply in the first three months of this year to 1.4 and 1.8 per cent respectively – Sydney’s lowest rate since Domain started counting.

But it’s the smaller cities and regions that are faring much worse, where there effectively is no rental market.

Adelaide hit the lowest vacancy rate ever recorded for a mainland capital – just 0.2 per cent.

Hobart improved the barest fraction, from 0.2 to 0.3 per cent, but in a market that small and tight, such a fluctuation from near-zero is meaningless.

Canberra and Perth remain at record lows of 0.5 per cent and Brisbane fell to 0.7 per cent.

Of course, from a landlord’s point of view, these are wonderful figures – a landlord’s market with rising rents and pressure on tenants not to complain.

While the Sydney and Melbourne vacancy rates aren’t as eyewatering as the other capitals, they are the cities that traditionally have to absorb the most foreign arrivals. The numbers are only heading in one direction.

An indication of particularly acute pain can be gleaned from the areas in greater Melbourne and Sydney with the worst vacancy rates.

In greater Sydney, the Blue Mountains 0.2 per cent, Camden 0.3 per cent and Wyong 0.4 per cent are all areas that attracted people for cheaper housing despite the lengthy commutes from the fringes.

In greater Melbourne, Yarra Ranges, Cardinia and Sunbury all recorded vacancy rates of 0.4 per cent.

Around Brisbane, Strathpine, Southport and Gold Coast North were just 0.1 per cent. To use a technical term, stuff all. Even the Caboolture hinterland was down to 0.2 per cent.

In chockers Adelaide, Playford, Onkaparinga, Marion, West Torrens and Tea Tree Gully were all 0.1 per cent.

In regions invaded by domestic tourists and COVID sea- and tree-changers wealthy enough to snap up second homes, the situation is dire.

Pick a reasonable country town and “we literally don’t have anywhere to live” is commonplace.

(And that particular one is for mother and daughter fortunate enough to be able to afford to pay for holiday rental accommodation.)

This disaster, both the society-changing macro failure spelt out by colleague Kohler and the individual trauma of people in rental and mortgage stress, is the result of decades of dud policies by governments of both stripes and at both state and federal level.

It is more than a little amazing that with such a crisis, housing isn’t front and centre of the election campaign.

In typical style, the Coalition announced a Band-Aid or two with the rhetoric aimed at first-home buyers while the Opposition carefully offered to do a bit more for public and social housing.

Neither comes near to dealing with the crisis, the narrow neoliberal nonsense of Mr Falinski’s report merely a raised middle digit to the people in crisis now and into the future.

And Mr Frydenberg’s bribery budget promises it will indeed get worse.

The sugar hit of the $2.1 billion HomeBuilder scheme – money that mostly went to people who didn’t need it – will have passed by the end of this year, leading to a decline in housing investment.

That’s one of the reasons GDP growth will drop to just 2 per cent in 2023.

Like rental vacancy rates, we are at a very low ebb.