Why our low opinion of politicians lets them get away with rorting

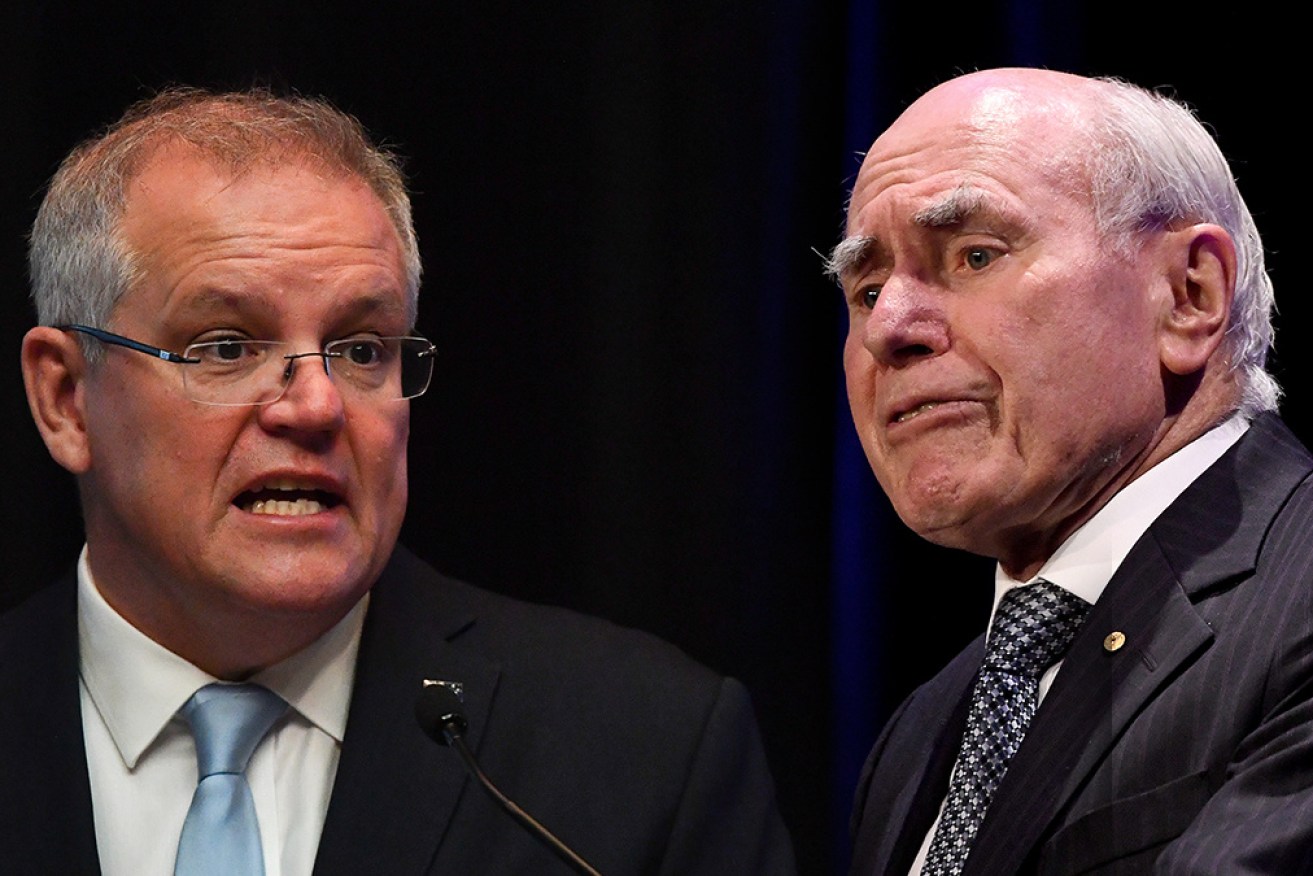

If Scott Morrison wants to know what not to do next, he can ask John Howard. Photo: TND

A lot of column inches have been devoted this week to the continuing sports rorts drama, with the most recent revelations making it very hard for the Prime Minister to deny his office was deeply involved in the malodorous affair.

That would be why Scott Morrison flat out refused to answer a question about the issue on Friday, ostensibly to keep the focus on the financial support the government is providing to keep the economy afloat as it is swamped by the twin effects of the drought/bushfires and coronavirus.

Let’s be clear – where political corruption exists, it should be exposed and cleaned out. The Labor Opposition and the media have every right – in fact an obligation – to apply the utmost scrutiny to the government’s corruption of its grant-giving processes.

Latest #SportsRort

Morrison calls a Global Pandemic before the rest of the world because his temperature is rising over scrutiny!

136 degrees of email could prove hazardous to his health.#auspol

— Teresa Randal💉x 5 😷 🦠x 0 (@RandaltsRandal) February 27, 2020

Australians need to know their government is spending taxpayer dollars for blatant political purposes, even if voters in some electorates are indirect beneficiaries of the largesse.

However, there is a second important point that needs to be remembered, one which can make it difficult to bring governments to account for such misbehaviour. Voters are frustratingly selective when it comes to becoming enraged about political malfeasance.

This selectiveness is based, in the first place, on our very low opinion of politicians. We expect them to lie and we’re not surprised when they rort the system. The only time we get angry is when the rorts only benefit the politician – such as the abuse of travel allowance.

In the case of ‘sports rorts’, there are hundreds of communities enjoying new or improved sports facilities, and they are probably finding it a bit hard to get angry about how that benefit was funded.

As I’ve written several times in the past, even though voters believed John Howard lied about the ‘children overboard’ affair, they still trusted him to do what was in the nation’s interest, particularly when it came to the economy. When that trust evaporated over Mr Howard’s WorkChoices policy, voters had no hesitation in turfing him out.

What a question time. @ScottMorrisonMP weazling his way to blame @senbmckenzie for very stinky #SportsRort revelations. Back dated approvals? Millions spent improperly during caretaker period? 73% of last round not recommended by Sport Aust? Dodgy as all hell. #auspol #qt

— Tanya Plibersek (@tanya_plibersek) February 27, 2020

Another way of looking at how voters trust, or don’t trust, politicians is explained in the compelling new book on the ALP Party Animals, by my colleague Samantha Maiden.

Veteran Labor campaign strategist Peter Barron notes in the book that Australian voters are notoriously risk averse, while former ACTU head, Chris Walton, argues that elections are usually won and lost on one question – who is the radical?

“Generally you will find whoever is able to paint the opponent as radical wins,” Mr Walton says.

So voters’ trust in politicians is not so much about who do we trust to tell the truth, but who do we consider the lesser risk, or who do have confidence in to do the right thing by the nation?

This knowledge is what gives Mr Morrison the conviction that he can get away with refusing to answer a question on sports rorts. Journalists might rightly seethe about the injustice, but most voters will remain comfortable and relaxed if they believe their trust in PM Morrison to manage the ‘risks’ remains well-founded.

The PM now realises this trust was shaken when he mishandled the summer bushfires. It’s been further eroded as the delivery of promised financial support for individuals and communities affected by the drought and bushfires has been interminably slow, adding to the active distrust of welfare recipients caught up in the robo-debt debacle.

PM just said Australians are ‘common sense people’. True dat. Common sense says 136 emails between you and Bridget Mackenzie is a #SportsRort.

— Dee Madigan (@deemadigan) March 3, 2020

With severe economic impacts of the coronavirus about to hit Australia, Mr Morrison knows this may be his last chance to prove he can manage the risks facing the nation. And no, that does not mean issuing a mandate for bigger supermarket trollies to cater for lemming-like toilet paper hoarders.

It will nevertheless be a tricky manoeuvre, requiring the government to relinquish the totem of its risk management superiority – the budget surplus – in favour of a new measure for doing what’s best for the nation. The Rudd and Gillard Labor governments tried to make ‘saving the economy’ the new measure, but it didn’t stick. Perhaps the second time’s the charm.

Failure to do so will permanently fracture voters’ trust in Mr Morrison. John Howard can tell him what happens after that.