Alan Kohler: Interest rate pundits hedge their bets

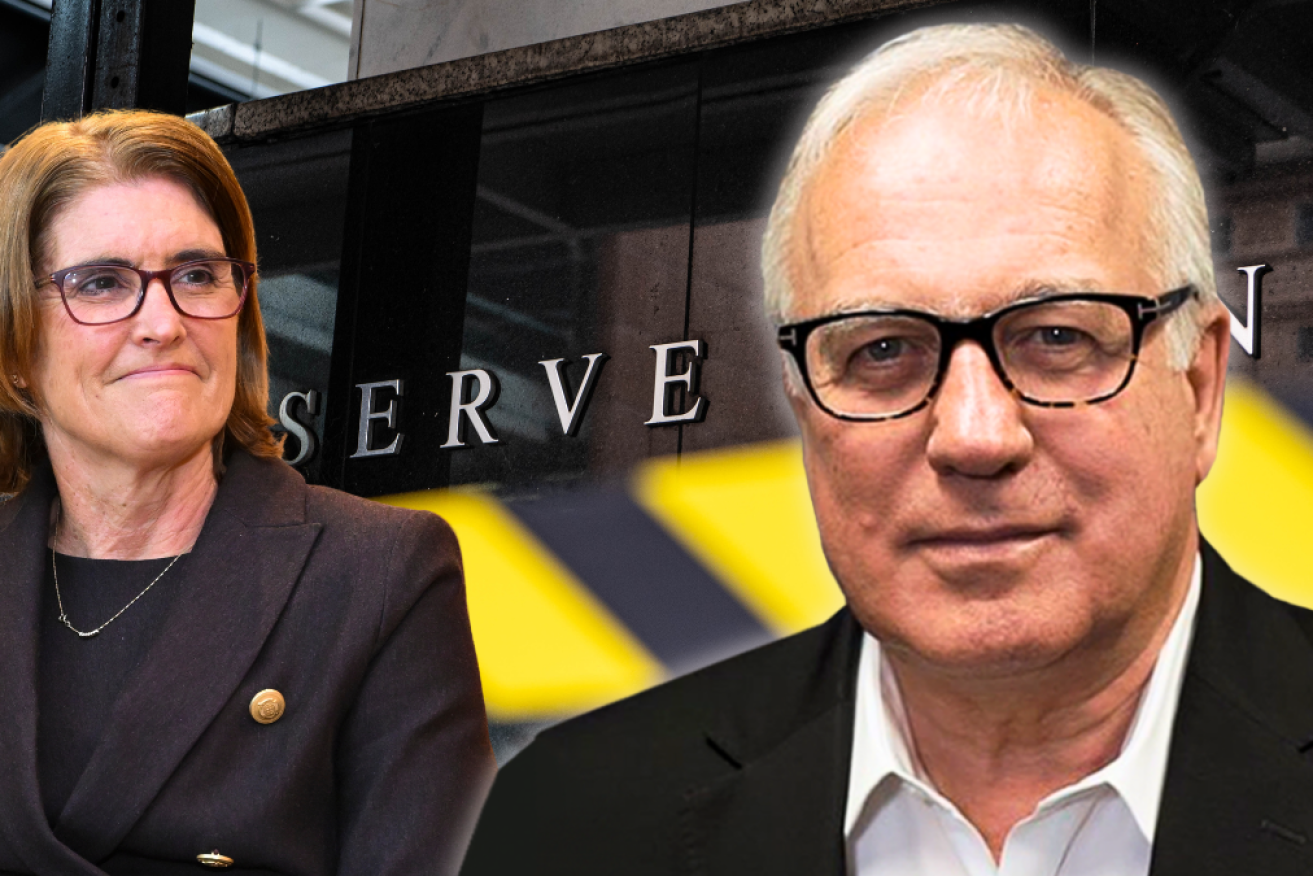

Photo: AAP/TND

There is often something for everyone in a Reserve Bank statement announcing its interest rate decision, especially when the decision is to hold.

This week, for example, the decision to hold was supported by the observation that “recent data are consistent with inflation returning to the 2 to 3 per cent target range over the forecast period”, which is late 2025.

“Rates have peaked” cooed the doves, which is shorthand for those who believe, or want, rates to have peaked.

But at the end of the statement, were these words: “Some further tightening of monetary policy may be required.”

“Aha, there is another rate hike coming,” said the hawks, which is shorthand for those who want, or believe there should be more rate hikes.

Common phrase

But something like those words are at the bottom of just about every governor’s statement that has ever been made. The exact phrase has been present in every statement of the past 12 months and when the RBA was in full hiking swing last year, the “may” was replaced by “will”.

So do we describe that as “tightening bias”, as many economists did this week, or just the pro forma sabre rattle in case we are inclined to relax? I’d say the latter.

Nevertheless, there were quite a few predictions after Tuesday of a rate hike on Melbourne Cup Day in November based on that so-called tightening bias, and the expectation that fuel prices would stay high.

Two problems with that, apart from the obvious one that saying some further tightening of policy may be required if inflation rises some more, is just a statement of the bleeding obvious.

First, the RBA pays little attention to fuel prices and mainly watches core inflation, which excludes them, and second, if fuel prices simply stay high, that will not result in higher inflation, which measures the change in prices; if fuel prices don’t keep rising, they won’t be inflationary.

That is not to say another rate hike is impossible – it depends on the data, specifically the employment data for September on October 19, and the September quarter CPI due to be released on October 25.

If unemployment falls, or doesn’t rise from the current 3.7 per cent, and inflation is shown to have increased (four months ago, that is), and if the US Federal Reserve has also hiked, then the RBA will probably hike.

Table mountain

I happen to think none of those conditions will be met and the RBA will not hike – not in November, or for a long time, and that we’re in for what some have called Table Mountain monetary policy, after the flat-topped mountain overlooking Cape Town in South Africa.

That is, after a rapid ascent, a lofty plateau. Philip Lowe left rates on hold for nearly three years after he took over in September 2016, but that was after a descent from 4.75 per cent to 1.5 per cent, so more canyon than plateau.

But as Yogi Berra wisely said, predictions are hard, especially about the future. As Federal reserve chairman Jerome Powell said, they are navigating by the stars under a cloudy sky, or as Governor Michele Bullock put it in her inaugural statement this week: “There are significant uncertainties around the outlook.”

And now there is another uncertainty around what the government means by full employment, and what it intends to do about it, if anything.

The definition in last week’s employment white paper that “everyone who wants a job should be able to get one without searching too long”, was actually plagiarised, word for word, from a speech by Michele Bullock in June.

But she also said that “our judgment is that we are at or even perhaps above estimates of full employment”, and that the RBA is predicting that unemployment will rise to 4.5 per cent next year and that this would be “not far off some estimates of where the NAIRU might currently be”, and “the economy would be closer to a sustainable balance point”.

What is full employment?

The NAIRU stands for non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment and is basically the RBA’s idea of full employment, or at least optimal unemployment – when it isn’t causing inflation to rise.

As I discussed here on Monday, last week’s white paper went to some lengths to tip a bucket on the NAIRU and made it pretty clear that the government’s definition of full employment does not mean unemployment of 4.5 per cent.

Does it mean the current unemployment rate of 3.7 per cent, or lower? They’re not saying, and it’s complicated.

And anyway, there’s nothing in this white paper, unlike the one in 1945, that says the government will actually spend money to achieve full employment, however defined.

So the only outfit with a clear plan to achieve full employment is the Reserve Bank, but they reckon that means more unemployment not less.

Over to you, Jim Chalmers.

Alan Kohler writes twice a week for The New Daily. He is finance presenter on ABC News and founder of Eureka Report