How Baby Shark became YouTube’s most-watched video of all time

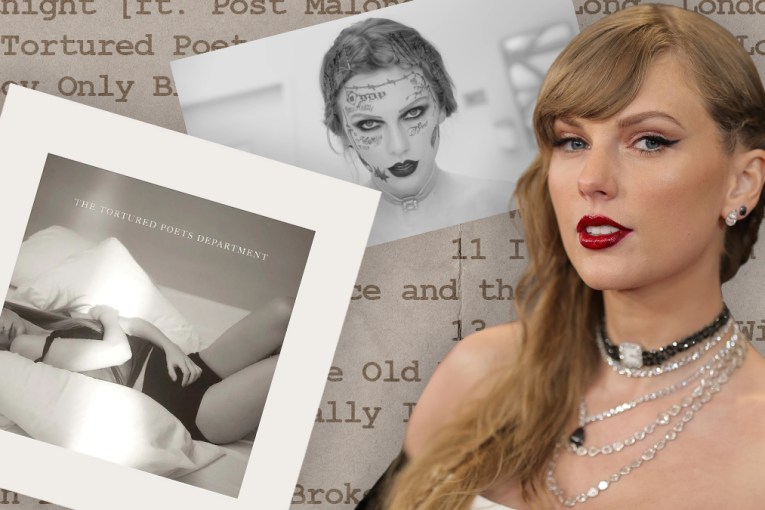

'Baby Shark's' impact has been felt far beyond South Korea's borders thanks to its viral social media success. Photo: Youtube

Four years after it exploded on the world stage, viral song and dance phenomenon Baby Shark has snatched the title of YouTube’s most watched video of all time.

The cute and innocent South Korean earworm this week overtook Luis Fonsi’s Latin pop hit Despacito to become the streaming site’s most watched video ever with more than 7.04 billion plays.

This means that if streamed back-to-back Baby Shark would now have played for more than 30,000 years.

Created by South Korean entertainment company Pinkfong in 2016, the children song’s success has reached astronomical levels globally, charting in the US Billboard Top 100 and also in the UK.

The song tells the story of a family of sharks, ranging from the baby up to its grandparents.

Pinkfong’s US CEO Bin Jeong told CNN the company saw immediate potential in the song’s performance.

“We saw it was going to be special,” Jeong said.

The viral hit has not been without controversy, though, with some experts warning that people were taking the ‘baby shark dance challenge‘ to dangerous extremes.

Pinkfong’s parent company SmartStudy has also been embroiled in litigation since 2019, with kids’ composer Jonathan Wright alleging the viral hit ripped off his 2011 arrangement of the nursery rhyme that inspired the song.

The case is currently being considered by South Korea’s Copyright Commission, with SmartStudy arguing that the wildly successful Pinkfong version was based not on Mr Wright’s arrangement but “on a traditional sing-along chant which has passed to public domain”.

K-Pop’s biggest stars driving influence in the West

Australian National University Korean studies expert Roald Maliangkaij believes K-Pop (Korean Pop) stars helped energise the song’s broader appeal as it started spreading internationally.

Idol groups like BTS and Blackpink began performing eccentric versions of the song on television to establish ‘aegyo’ – a cuteness factor akin to the Japanese concept of ‘kawaii’, Dr Maliangkaij said.

“It’s kind of this style which emphasises a child-like cute innocence, and using kids songs plays into it,” he told The New Daily.

“The idols who are engaged with the K-Pop world will perform on stage and in TV shows where they have silly conversations and kind of embarrass themselves, and one of the big things about being an idol is being modest.”

Dr Maliangkaij said Australian parents have become intrigued by K-Pop’s lack of sexualised and drug-fuelled lyrics, and the simple repetitive nature of Baby Shark helped the song gain fame far beyond Korea’s borders.

“I guess in Australia in particular, we do have a fairly strong second- and third-generation Asian population that is interested,” he said.

“For parents, it’s a dream come true. It’s like it was dreamed up by a parent, rather than industries.

“K-Pop has received a lot of support from younger generations because America seems to have collapsed as the place where pop culture is being driven.”

Social media’s role in Baby Shark’s success

Some have attributed the song’s social media success to the music video’s eccentric choreography and catchy lyrics.

It has inspired online dance challenges on recently adopted platforms like Tik Tok, instructional YouTube videos and covers reinterpreting the song’s childish appeal.

Tweet from @Zoes_Place

The craze hit fever-pitch levels when celebrities danced to the viral hit on American primetime television similar to their Korean counterparts, before the tune was covered on James Corden’s The Late Late Show in September 2018.

Deakin University digital anthropologist Crystal Abidin said there’s a major incentive for social influencers to participate before a viral trend disappears.

“With every other viral trend, there is a lifecycle of internet virality, and you see when something takes off, there’s a big incentive for others to cash in,” Dr Abidin said.

“The commercialism of the song, where the song extends beyond original corporate ownership to people like influencers, is how we know something has become mainstream.”

Dr Abidin said Western audiences, who may consider some of the song’s lyrics “gibberish and devoid of meaning,” helped its remixing potential.

“They’ve broken out of the east Asian market and broken into the mainstream for English language audiences,” she said.

“Popular Western media coverage expressed shock that [the song] infantilised east Asian culture, but Baby Shark represents the ‘exotic’ and young audiences coming together to produce this thing that’s gone viral.”