Alan Kohler: How Japan escaped neoliberalism and lived happily ever after

The Reserve Bank could learn a lot from Japan, writes Alan Kohler. Photo: TND/Getty

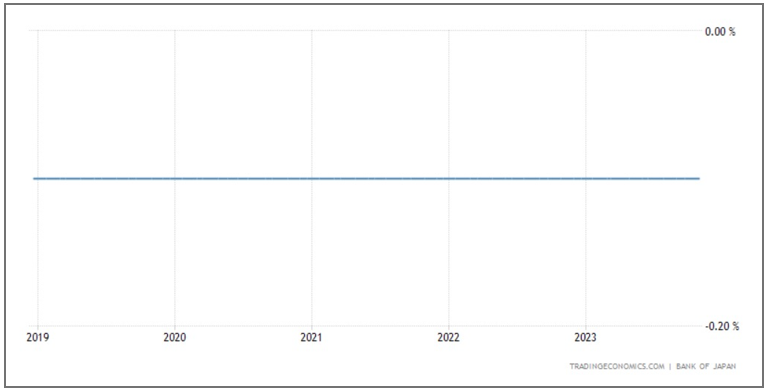

Here’s a graph of the Bank of Japan’s key interest rate over the past five years:

To be clear about what you’re looking at: Japan’s main interest rate was minus 0.1 per cent before COVID-19 came along, stayed there throughout the pandemic and is still minus 0.1 per cent. And no talk of a rate hike now.

We don’t need a graph of the Reserve Bank of Australia’s main cash rate to tell us what happened here: It was cut from 0.75 per cent to 0.1 per cent in 2020, stayed there for 15 months and then, in May last year, was increased rapidly to 4.35 per cent over 18 months, with the latest hike just last month to make sure, accompanied by warnings that there might be another one.

You probably think Japan has left interest rates unchanged at minus 0.1 per cent because it’s a basket case, in recession and deflation and can’t raise interest rates. But that’s not true.

Inflation has increased from minus 1 per cent (deflation) in 2021 to 4 per cent and although the economy shrank in the September quarter this year, growth has averaged 0.5 per cent per quarter since the start of last year – not a boom, that’s true, but not a recession either.

So what’s going on? How come the people of Japan get to have no rate hikes while we – and Americans and Europeans and British – get hammered with them?

Well, Japan is the crazy uncle at the economic Christmas barbecue, laughed at pityingly and ignored, while we all get on with discussing serious matters, like the Taylor Rule, which is the theoretical formula central banks use to calculate what interest rates should be for a given inflation and growth rate.

But the truth is Japan’s doing fine, and is not crazy at all. Everyone’s happy, unemployment is 2.5 per cent and has been under 3 per cent for five years, politics is stable and polite and there’s no shortage of infrastructure or housing – house prices have been fairly stable for 30 years.

But – and this is a pretty big “but” – Japanese government debt is 265 per cent of GDP, second highest in the world after Venezuela, which is definitely not the company you want to be in. Australia’s is 34 per cent and America’s 130 per cent, which is starting to get everyone worried.

Print it and buy it back

In fact, the Japanese government has owed more than 200 per cent of GDP for more a decade but has been happily running massive budget deficits the whole time, no pressure to balance the books, either politically or economically.

Why? Because the interest rate on that debt has fluctuated around zero, plus or minus 0.1 per cent – for the whole time, and has lately “soared” to 0.7 per cent, so repayments are negligible.

And that’s because the Bank of Japan buys most of it, using freshly created money, to keep the interest rate low.

The BoJ – owned by the government of Japan – owns 53 per cent of all government debt and is buying it every day.

The property crash happened more than 30 years ago, the GFC 15 years ago and the pandemic is over as well; these days the Japanese central bank prints money simply to support government spending while allowing taxes to stay low, and to ensure that interest rates for the government – and everybody – also stay super low.

How do they get away with that? Won’t the sky fall in?

Japan has simply stopped worrying about budget deficits because they figured out that the central bank can print money and buy the debt that results so it doesn’t matter. Needless to say, this is not orthodox economics.

Japan was not bitten by the neoliberal mosquito that infected most other Western countries in the 1990s, because it had a property bubble in the late 1980s, and then a devastating bust in 1990, so that free markets got a bad name in Japan, and economic orthodoxy was defenestrated.

Meanwhile progressive governments in America and Australia – Bill Clinton and Hawke/Keating – reacted to the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the discrediting of the command economy, with the assertion of capitalism: Privatisation, deregulation, globalisation and budget surpluses – called economic rationalism at the time, and now neoliberalism.

Japan couldn’t care less what other countries were doing because it was fighting for survival, battling chronic deflation and depression after the property collapse.

Endless deficits? No big deal

Fiscal and monetary policy were dialled up to 11, and while there was a budget surplus in 1990 at the peak of the property bubble, it has been deficits ever since, big ones.

Government spending has supported social services and infrastructure and there is simply never any shortage of money.

The Bank of Japan has been printing money and buying the government debt on and off since 2001, and Japan has become a model of Modern Monetary Theory, not to mention fiscal and macroeconomic sacrilege. The government spends what’s needed and doesn’t care about the deficit, and simply ignores the economic orthodoxy that says the budget must be brought back to surplus.

In a week or two, the Australian government will release the mid-year economic and fiscal outlook (MYEFO) statement and Deloitte Access Economics says it will be back in surplus.

Treasurer Jim Chalmers will bask in its warm glow, proud of keeping spending tight and having a surplus, the Opposition will struggle to find something to criticise, and economists will nod their approval.

And everyone will continue to ignore what’s going on in Japan.

Alan Kohler writes twice a week for The New Daily. He is finance presenter on the ABC News and also writes for Intelligent Investor