Madonna King: Pandemic response leaves lingering distress for nation’s children

The pandemic response might be just as big an ogre as COVID-19 itself.

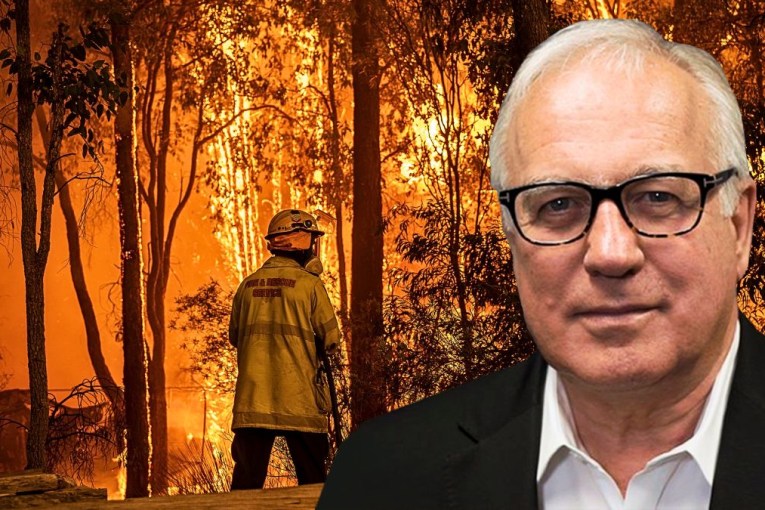

That’s a key takeout of Peter Shergold’s stellar report into how Australia handled the arrival of COVID-19 on our shores.

And his warning is clear: If we don’t assess what has been learnt from a pandemic that killed people, upended careers and provided new mental health challenges, we will make the same mistakes in the future.

We can’t afford that to happen.

For the past three years, I’ve interviewed teenagers as part of research for two books – Ten-Agers and L Platers. The former is targeted at parents of seven to 11-year-olds; the latter for parents of 14- to 18-year-olds.

And the heartbreak brought by COVID-19, and the uncertainty it created in their lives should be the subject of a commission of inquiry. It is raw and ongoing.

Anxiety in primary schools

School principals are seeing it in a new anxiety in primary school. Universities are seeing first-year students act more like 15-year-olds. And parents are seeing it in the hopes and dreams of their children.

“At the end of this pandemic, will life ever go back to normal again, and when family are sick, will they ever get better?” That child is just 11.

Others – in years 4, 5 and 6 – told me of being unable to sleep unless their mother lay in the same bed, how they cried because they missed their friends and school sport, and thought they might never see their grandparents and teachers again.

Others couldn’t define ‘coronavirus’, didn’t know the difference between internationally and locally acquired, and will not stay in a hotel ever, because that’s where the “sick people stay”.

Those children are now in years 6, 7 and 8. How are they faring?

Parents’ experiences

Parents saw the enormous impact too – despite it being largely ignored by government.

“She does not want us to use the word ‘corona’,” one told me.

“She keeps going over and over the problems (i.e. why would someone eat a bat?),” another said.

And another: “She is very sad and glum. It was the first time we have ever seen this characteristic in her. We asked if she wanted to talk to a friend, but she said that she had nothing to say.”

And this: “She was washing her hands so much they were cracking and bleeding.’’

Kids Helpline saw a spike in calls tracked directly to lockdowns.

“COVID has caused a lot of strain on my Dad. He lost his job. Normally he is an angry person but during the pandemic he got angrier and meaner,’’ one teen told me.

“COVID has made me lonely. I’m not big on social media. I felt so isolated,’’ another said.

“I’m more careful of the people I associate with. I’m not meeting any new people. There are no new people. If something happens it’s a much bigger deal,’’ a third said.

School principals have seen an escalation in anxiety in primary school children; some worry that something bad is looming, always.

In one school, those in year 5 were taught, explicitly after lockdown, how to look at someone. They’d forgotten how, after lockdown.

Uncertainty shadows children

In Melbourne, more than a dozen year 12 students – who had decided on degrees requiring top marks – have put off going to university.

“I just want to stop studying,” one told me.

Where are those bright, future leaders now? Others have still not returned to school; they just can’t.

Good stories popped up, too: Many children spent more time with the family breadwinner, usually their father, who worked at home during the pandemic. Students on the autism spectrum blossomed, based on anecdotal research. Bullying dipped.

But the uncertainty brought by COVID-19, perhaps more than the pandemic itself, provided an economic, social and health challenge that continues to shadow our children.

Shergold, the chancellor of Western Sydney University and former head of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, was joined by businesswoman and former chancellor of the University of Wollongong Jillian Broadbent, University of Queensland chancellor and retired diplomat Peter Varghese, and Isobel Marshall, the 2021 Young Australian of the Year.

This wasn’t a political inquiry, and that makes its findings all the more valuable. But it is the stories of excessive border control, domestic violence, isolation and trauma that many lived through that still needs to be addressed.

Hindsight provides wonderful insight. But we’ve got to do better next time. This report – Fault line: An independent review into Australia’s response to COVID-19 – provides the blueprint.