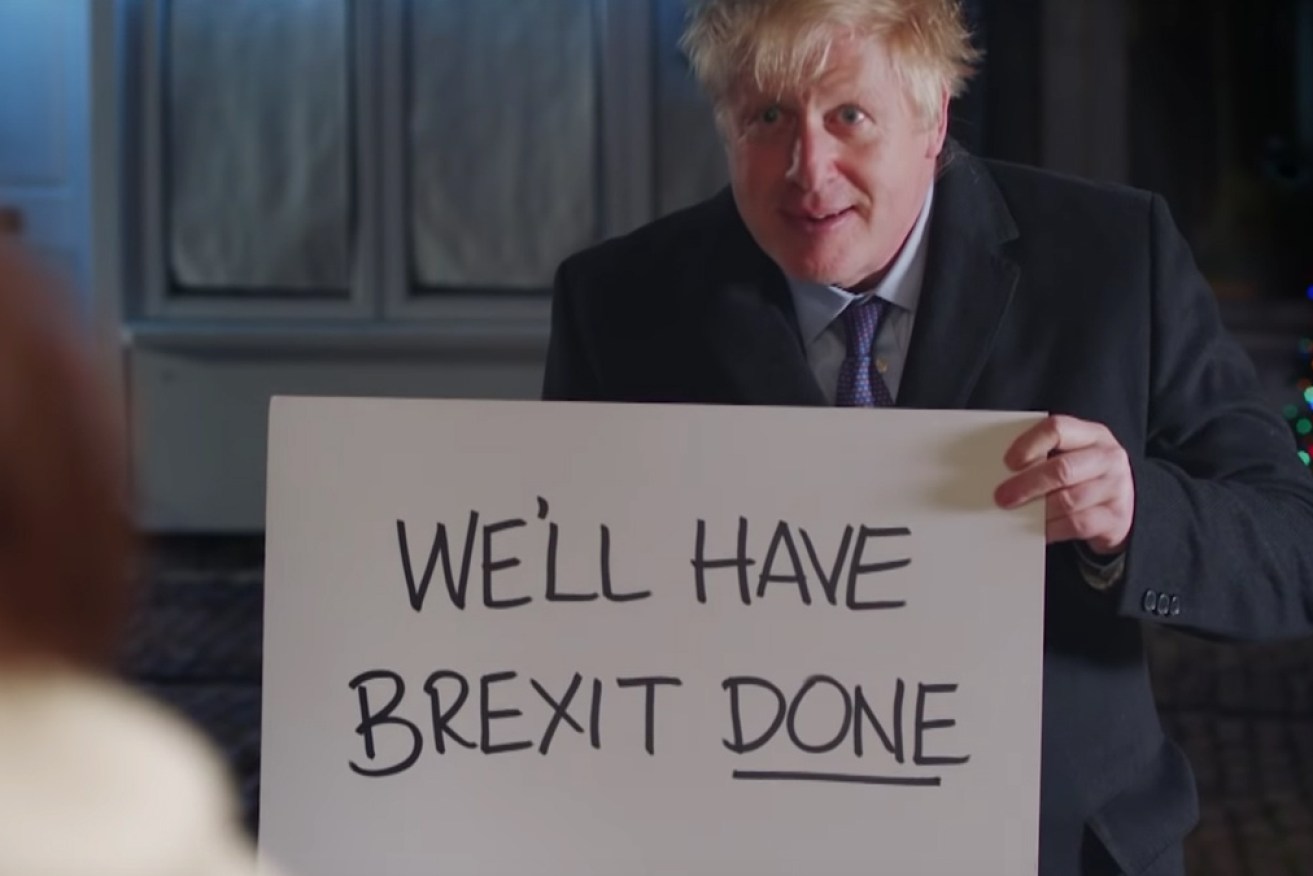

Brexit: How Boris Johnson didn’t celebrate a historic moment

PM Boris Johnson's promise to finalise the UK's divorce from Europe isn't going well. Photo: AAP

At 11pm in London (or 10am Australian Eastern time on Saturday), the United Kingdom finally left the European Union after a three-and-a-half year political battle that propelled the former journalist into 10 Downing Street.

But the Prime Minister’s no-show gave the event an air of anti-climax.

Aware that he has failed to unite his deeply divided country behind Brexit, Johnson ordered his ministers to avoid the sort of triumphalism that might inflame the feelings of the millions of Britons who still believe that ending the UK’s 47-year membership of the EU is a calamitous mistake.

So while a beaming Brexit Party leader Nigel Farage bounced around a stage outside Parliament, telling a few thousand cheering supporters that “this is the greatest moment in the history of modern Britain” and “we have got Boris singing our song”, the PM himself stayed out of sight at a private party in Downing Street.

Instead of the usual Address to the Nation that would be recorded by a major broadcasting service, Johnson pre-recorded a speech with his own video crew a day earlier and released it on social media, giving him complete editorial control as he acknowledged the “sense of anxiety and loss” felt by many Britons.

11pm tonight marks the point of no return.

Once we Leave, we will never rejoin the European Union.

Time to celebrate! pic.twitter.com/KXQ4f2hTDu

— Nigel Farage (@Nigel_Farage) January 31, 2020

Activists on either side of the bitter Brexit debate held parties around the country to jubilate or commiserate but the dominant mood seemed to be one of relief that the ugly parliamentary stalemate sparked by the narrow 2016 referendum vote in favour of Brexit had finally been resolved by Johnson’s general election victory in December.

Little will change in the lives of citizens and businesses until the end of a transition period on December 31, and the negotiations that will determine the extent of those changes have not even begun.

Boris Johnson was notably absent from the official Brexit moment, leaving revellers to make their own fun. Photo: Getty

But there was no hiding the significance of the UK formally abandoning the world’s largest free trade area and most successful effort at sharing sovereignty across borders.

“This is the moment when the dawn breaks and the curtain goes up on a new act,” Johnson said in his pre-recorded statement. “My job is to bring this country together now and take us forward.”

Political scientist Sir John Curtice spelled out the scale of that challenge, noting that Johnson’s election victory over the deeply unpopular Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn did not mean he had convinced the public of the merits of Brexit.

“Polls conducted during the campaign suggested – as they had done for the last two years – that there was a small but consistent majority in favour of remaining in the EU,” Sir John wrote for the BBC.

“On average, the last half dozen polls before the election put Remain on 53 per cent and Leave on 47 per cent.”

The public had become increasingly sceptical about the promises by Johnson and other Brexiteers’ of the supposed economic benefits of leaving the 28-nation EU, with one survey during the election finding that 56 per cent of respondents expected Brexit to hurt the economy and just 21 per cent predicting it would help.

The nation’s top business leaders, the Bank of England and most economists agree that Brexit will cost jobs, investment and growth so the current relief at the end of the stalemate could easily give way to anger if those fears are vindicated when the transition period ends.

Johnson’s call for unity will not be helped by the unusually divisive way he handled the Brexit debate, accusing opponents of “surrendering” and “collaborating” with Europe and ultimately expelling from the Conservative Party former Chancellors Ken Clarke and Philip Hammond for not backing his Brexit vision.

His “all or nothing” approach fuelled the Brexit rift which split many British families and workplaces and has left simmering tension between Remainers, who tend to be younger, wealthier, better educated and more internationally-focussed, and their Brexit-backing elders.

Nowhere are the Brexit divisions more obvious than in Scotland, where the departure from the EU was marked by “Missing EU Already” rallies and candlelit vigils under the title “ Leave a Light On”, urging the EU to save a space for Scotland to rejoin if it can break away from the UK.

While Downing Street was lit up in the colours of the Union Jack, Scottish Government buildings were lit in the blue and yellow of the EU flag.

A YouGov poll this week showed Scottish support for EU membership has risen to a remarkable 73 per cent, up from 62 per cent in the 2016 referendum.

There is no guarantee that Scottish voters will vote for independence if there is a referendum but Johnson faces a realistic threat that Brexit could see both Scotland and Northern Ireland eventually choose to leave the UK.

In the shorter term, the PM has to try to keep his own wildly optimistic promises of a booming post-Brexit economy and new global influence, and he will have no excuses if things go wrong.

His predecessors David Cameron and Theresa May campaigned against Brexit in the 2016 referendum but Johnson enthusiastically led the pro-Brexit campaign, personally promising goodies such as a new trade bonanza and a fanciful £350 million a week of extra spending for the NHS.

His government’s own forecasts suggest that the benefits of signing new trade agreements with countries such as Australia and the US will be heavily outweighed by new barriers to trade with its neighbours and largest trading partners.

The Brexit Celebration is underway! https://t.co/zFw0zEdLr8

— Reform UK (@reformparty_uk) January 31, 2020

Trade economists doubt the UK’s chances of getting a good deal from Donald “America First” Trump as a nation of 66 million rather than as part of the 512 million-strong EU.

Australia certainly has a wonderful opportunity to take the hardest possible line in its pending trade negotiations with the UK, given the British Government’s desperation to find new deals and prove to its voters that it has not led them into the trade wilderness.

Indeed the Australian government could take the opportunity to dust off some of the longer-standing items on its bilateral wishlist, such as the UK’s stubborn and unfair refusal to give British pensioners living in Australia the same annual pension increases that it gives to its pensioners living in countries such as the US and the Philippines.

If Canberra is ever going to enjoy leverage over issues like that it is this year, when the UK will be negotiating with Australia and others at the same time that it holds its most important talks of all, with the EU.

Johnson has hugely increased the pressure on himself by vowing to get a free trade deal with the EU by December 31.

The EU will spend February working out its own negotiating goals, and other procedural problems mean that there will actually be only about eight months of negotiations.

Johnson’s preferred model is a deal like the one Canada recently reached with the EU. For some context, that deal took eight years and Canada has nothing like the intricate ties that link the EU and British economies.

The new European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen says Johnson’s deadline is “impossible”.

By boxing himself in to that timetable Johnson has simply increased the danger of ending with no free trade agreement with the EU, leaving him more desperate than ever for a deal with countries like Australia.