Former NSW premier Neville Wran dies

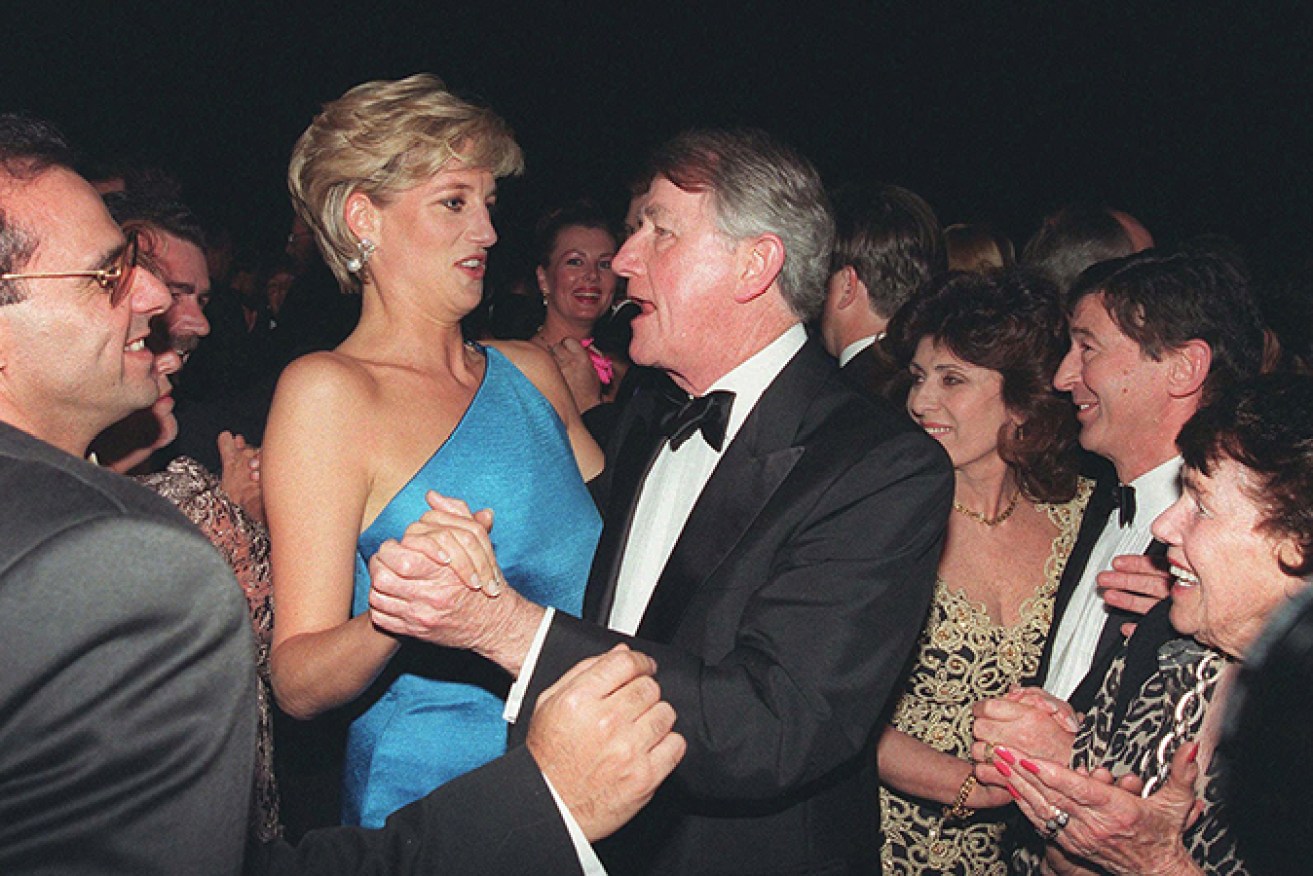

Wran dancing with Princess Di at the Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute dinner.

Long-time NSW premier Neville Wran has died after a long illness, aged 87.

His wife Jill Hickson said in a statement to AAP that Mr Wran died just before 6pm on Sunday evening.

Wran arrives at the memorial service for Margaret Whitlam in 2012.

Ms Hickson was with him and all his family close by.

Mr Wran has been suffering from dementia and has been under special care for the past two years.

“This is of course a very sad time for us all, but in fact a blessed release for Neville,” Ms Hickson said.

“Dementia is a cruel fate and I have been grieving the loss that comes with it for some years. But I hope now, especially this political climate, people will join me in celebrating the life of a great man, a true political hero.”

A great man, a true political hero

She paid special tribute the nursing staff of Lulworth House who had been caring for the former premier.

“They really are angels,” she said.

He led the Labor government in NSW from May 1976 to July 1986.

Nifty Nev showed Labor how to win again

Nifty Nev, as he was known, was NSW premier from May 1976 to July 1986 and ALP national president for six years.

The worldly lawyer from working class Balmain, for whom winning was everything, never lost an election and was a political rarity in deciding when to retire undefeated.

His success was built on ruthlessness, authority in party and parliament, an unerring instinct for what the voters wanted and pioneering exploitation of television’s political clout.

Neville Kenneth Wran, was born in Balmain on October 11, 1926, the last and eighth child of Joe and Lillian Wran.

He died on Sunday, aged 87, after suffering from dementia and under special care in a nursing home for the past two years.

Although his memories of Balmain were warm – “Balmain boys don’t cry,” he famously said when under pressure many years later – he wasn’t much good at fighting or football, the most highly prized skills there.

“Balmain boys don’t cry,” he famously said when under pressure

But he was smart, winning a scholarship to Fort Street High, the school that’s helped launch the glittering careers of generations of working class kids.

From there he won a Commonwealth Scholarship to Sydney University to study arts and law, where he made his mark as a debater and – his first love – actor.

He considered an acting career, but decided the law would pay better. However his thespian talents served him well before juries and in politics.

Aged 20 and still at university, Wran married Marcia Oliver, a former Tivoli showgirl with a son from a previous marriage whom Wran adopted. They had two children.

He worked as a solicitor for 10 years, doing many workers’ compensation cases, which gave him contacts with important trade union officials, before going to the bar.

There he developed a reputation in industrial and negligence cases, regularly winning big damages from juries. He became a QC in 1968.

Wran joined the Labor Party in 1954, but for more than a decade was relatively inactive. However he was steadily developing firm links with major union figures. A case involving a union turf war brought him to the attention of NSW Labor boss John Ducker.

Wran and his wife Jill.

In 1970 Wran won a seat in the Legislative Council, the NSW upper house, then more a comfortable club for loyal party servants than a launching pad for ambitious young politicians.

Wran’s aggressive eloquence soon made a mark and he became Labor’s deputy leader in the council in a year and leader in 1972. It was a rapid rise, but in the wrong chamber.

Ducker decided Wran was the man to beat the Liberals – assuming, as he correctly did, that Labor leader Pat Hills failed against Premier Robert Askin in 1973.

But getting the factionally unaligned Wran the leadership involved enormous manoeuvering.

Ducker went first to his factional enemy, the Left. Its leader, Jack Ferguson (Martin and Laurie’s father), took some persuading but eventually agreed, while doubting the move would succeed. Ferguson was to become Wran’s trusted deputy.

Wran was shoe-horned into a safe lower house seat, Bass Hill, and after Hills lost the election, he challenged.

It couldn’t have been closer. On the second round Wran and Hills were tied at 22-each, with Wran controversially declared the winner because he’d received one more vote in the first round.

Wran was lucky. Michael Cleary, a Hills supporter, had lost his Coogee seat by 15 votes and appealed to the Court of Disputed Returns. A new ballot, which Cleary won, was ordered, but that was too late to save Hills.

The new leader was also lucky in the political cycle. The tough and wily Askin retired mid-term and was replaced by the bluff Tom Lewis, over whom Wran soon established ascendancy. After 14 months he was replaced by the more efficient Eric Willis, but by then it was the Liberals who seemed in disarray.

Wran, more than any Labor leader since wartime premier Bill McKell, worked hard on the bush – starting with the Mudgee Show where, after some coaching from a country-bred journalist, the quintessential city slicker did a decent job of handling sheep and cattle.

Wran dancing with Princess Di at the Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute dinner.

In Sydney he concentrated relentlessly on a few key issues – health, education and, above all, public transport.

He won over the NSW press gallery through friendliness, accessibility and generating excitement and used television more than any of his predecessors. He was the first to regularly give the cameras newsworthy backdrops for his crisp comments.

His long-time press secretary Brian Dale says he was the first Australian political leader to understand fully the power of television.

By the time of the May 1976 state election, Labor was in a melancholy state. Gough Whitlam had been thrown out and the party was in office only in South Australia and Tasmania. Some wondered if it would survive.

The election couldn’t have been closer. After a 10-day wait, and winning one seat by 44 votes and another by 74, he was able to form a government with the support of an independent.

According to Dale, Wran wouldn’t have stayed if he’d lost. As a QC he’d been earning $150,000-$200,000; as opposition leader $23,000. He was prepared to take the pay cut for only three years.

Shortly after the election Wran and his wife, who’d separated the previous year, divorced. Two months later he married Jill Hickson, with whom he had two children.

In government, Wran insisted on cabinet solidarity. Moderation, caution and stability were his bywords.

Journalists Mike Steketee and Milton Cockburn, in their unauthorised biography of Wran, say he usually got his way in cabinet by a mixture of subtle manipulation of the agenda, the use of committees to defuse issues, patient negotiation and, as his authority grew, foul-mouthed bullying and occasionally tantrums.

His authority was also increased through a strengthened Premier’s Department.

Helped by the Liberals’ failure to find an effective leader, the 1978 election was the first of two “Wranslides”, won under the slogan of “Wran’s our Man”. A second Wranslide followed in 1981, and although he lost some seats in 1984, he retained a big majority.

The 1978 election was the first of two “Wranslides”

He was considered so popular that in the 1980 federal election he and Bob Hawke joined Bill Hayden as a Labor leadership triumvirate.

He seriously considered going to Canberra and aiming for the top, but the circumstances were never quite right. He was also deterred by a throat operation that left him with a croaky voice.

Wran announced his July 4, 1986 resignation to a shocked Labor conference. He’d then held continuous power longer than any other NSW premier, though Bob Carr was to surpass his record.

At a news conference after the announcement, he said his main objective had been to keep beating the Liberals “and I’ve had amazing success at doing that”.

He also hinted that he was bored, saying “after a decade, there’s a certain repetitive quality about state politics”.

Wran’s legacy was considerable, though perhaps not as great as his authority could have achieved.

His governments reformed the upper house, greatly expanded the national parks, strengthened consumer protection, introduced a cautious system of Aboriginal land rights and brought in anti-discrimination laws.

Neville Wran in 2001.

He changed the face of Sydney – from moving hospital beds from the inner city to the western growth areas to developing Darling Harbour.

He reckoned his greatest achievement was enabling people to get a drink on Sunday.

Steketee and Cockburn, however, say he was rarely in the vanguard of change because of his concern for popular opinion.

It wasn’t until 1984 that he moved on homosexual law reform; his prison reforms lasted only as long as the public accepted them; he established the Anti-Discrimination Board, but was reluctant to act on its recommendations; and did nothing about freedom of information.

Yet to others, this constant benchmarking against community attitudes was a supreme virtue.

Graham Richardson, a key Labor machineman for much of the Wran decade, says he read the electorate with unerring instinct.

Wran and his government also became involved in damaging scandals.

In 1983 he stepped aside while a royal commission examined allegations he’d tried to influence a magistrate over a misappropriation hearing against rugby league boss Kevin Humphreys. He was cleared.

Prisons Minister Rex Jackson was jailed for selling early releases and Chief Magistrate Murray Farquhar was jailed for perverting the course of justice. Senior police were caught up in corruption scandals.

Wran himself was fined $25,000 for contempt of court after declaring his belief in the innocence of his old friend Lionel Murphy, the High Court judge facing a charge of attempting to pervert the course of justice.

After politics, Wran excelled in a third field, business. He ran a cleaning company and, with future federal Liberal leader Malcolm Turnbull, a merchant bank. He had a swag of company directorships.

He became a Labor icon, a regular at big party celebrations. With Hawke, he wrote the post-mortem on the federal loss in 2000.

Yet he remained an enigma.

A cabinet colleague said he was like a set of Chinese boxes: “Open one box and you will always find another box inside.”

He had many colleagues, but few deep friends. Some saw him as a chameleon, moving seamlessly from elegant, arts-loving sophisticate to beer-drinker in working class pubs.

His wife Jill once said: “When I first met Neville, he didn’t really like people, he didn’t like himself. He had few close friends. I think I can truly say I was the first person that he … unlocked himself to.”

Or, perhaps, to his much older brother Joe. One of Wran’s unpublicised habits, even at the height of his powers, was to pick up some fish on Sunday mornings and take it to Joe’s modest Balmain home for lunch.

Even his “Balmain boys don’t cry” had a qualification.

“But if you prick us with a pin, we bleed like anyone else,” he added.

-AAP