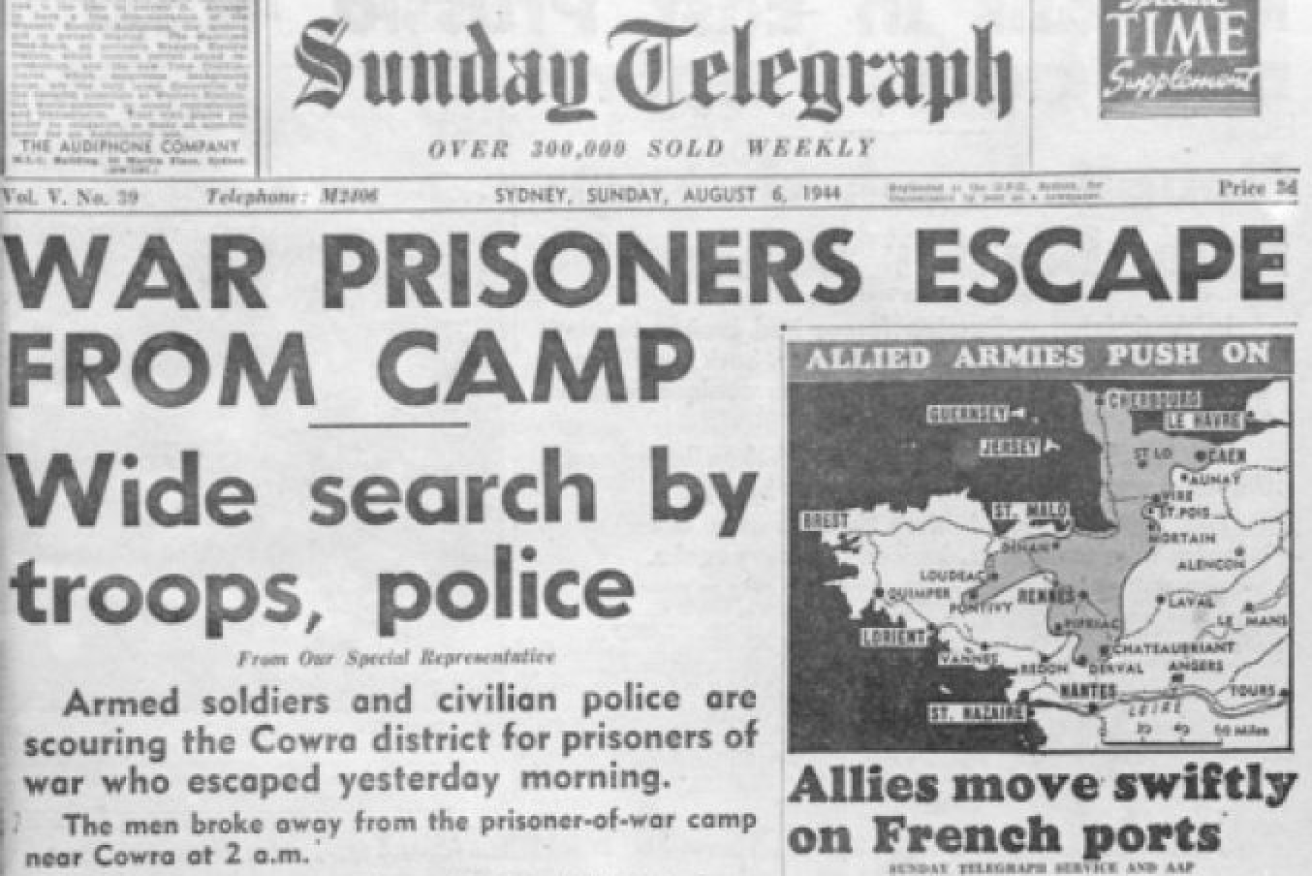

The bloody day rampaging Japanese POWs brought the war to Cowra

The POW uprising stunned Australians who had assumed the homefront was safe from the ravages of war. Photo: Trove/ABC

It started with a bugle blast and reached a crescendo of machine gun fire and death as hundreds of screaming Japanese prisoners armed with homemade weapons charged the wire and guards of their prison camp.

As the sun rose over Cowra, NSW, 75 years ago this month, bodies lay everywhere, the vast majority of them Japanese, many dead from gunfire.

Others had taken their own lives, some by hurling themselves into flaming buildings, some at the hand of fellow prisoners. In all, 231 (some references say 234) Japanese died in and around the camp.

Among the dead were three Australian camp guards. Two, Privates Benjamin Hardy and Ralph Jones, were overwhelmed and bashed and stabbed to death as they fired a Vickers machine gun into the charging Japanese.

For their heroism, both were posthumously awarded the George Cross, though that wasn’t announced until 1950. During the war, Australian authorities wanted to do nothing which might invite retaliation against the 22,000 Australians in Japanese hands.

Also killed were Private Charles Shepherd, stabbed during the breakout, and Lieutenant Harry Doncaster, jumped and stabbed by a group of prisoners during the subsequent roundup.

A memorial honours Australians killed during the breakout. Photo: Australian War Memorial

Historian Mat McLachlan says this was the biggest battle on the Australian mainland during World War II. And it really had nothing to do with prisoners seeking their freedom.

“The Japanese plan was to launch a big riot, to break out of the prison camp, to take over the machine guns and then turn those machine guns on the Australians,” he said.

“And then they were going to attack the Army training camp…with the intention of killing as many Australian soldiers as they could before they were themselves killed in a glorious death on the battlefield.

“There was definitely huge amounts of shame that they had been captured but there was so much more to it than that. The breakout was their way of attempting to erase that shame with violence, with combat in battle.”

The prisoner of war (POW) camp at Cowra was created in 1941, initially to house Italians captured in the Middle East.

By August 1944, what was termed No 12 POW Group comprised four separate camps in a common facility, two housing Italians, one with Japanese soldiers and the other holding Japanese officers along with captured Korean and Formosan labourers.

Unlike POWs of Japan, those in Australia were treated fairly, with adequate food, accommodation and medical care.

Just a few of the homemade weapons collected after the mass attack. Photo: Australian War Memorial

On the eve of the breakout, the Japanese Camp B, held 1104 prisoners, mostly junior soldiers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs) captured in New Guinea, plus some pilots and sailors.

Unlike Italian POWs, who were on the whole happy to be well away from the war, the Japanese weren’t. Camp authorities were aware of growing unrest.

In June, a Korean informant warned a mass breakout was planned and various measures were taken to strengthen camp defences, including bringing in additional automatic weapons. It was decided to separate the officers and NCOs from their men

The precipitating event was the announcement that the officers and NCOs would be relocated to a separate camp at Hay, NSW with the move to take place on August 7.

Camp B leaders alerted to the move about 1.30pm on August 4 and that produced immediate and intense agitation – which erupted at 1.50am on August 5.

The trigger for the breakout was the sound of a bugle, apparently played by pilot Hajime Toyoshima, captured after his Zero fighter crashed on Melville Island following the raid on Darwin on February 19, 1942. That made him the first Japanese POW captured in Australia. He did not survive the night.

Many POWs took their own lives , like this prisoner who hanged himself in the camp kitchen. Photo: Australian War Memorial

Official historian Gavin Long described what happened: “A sentry fired a warning shot. More sentries fired as three mobs of prisoners, shouting Banzai began breaking through the wire, one mob on the northern side, one on the western and one on the southern,” he wrote.

“They flung themselves across the wire with the help of blankets. They were armed with knives, baseball bats, clubs studded with nails and hooks, wire stilettos and garrotting cords.”

Prisoners set fire to their huts. The guards, members of the 22nd Garrison Battalion, opened fire, mowing down charging prisoners and others – three of the four Australians wounded that night were hit by stray bullets.

Prisoners failed in their immediate objectives – freeing officers and taking over a machine gun. Many escaped the gunfire in a drainage ditch, emerging meekly once the shooting stopped.

Others fled into the surrounding countryside, surrendering without incident to searchers and even to local farmers who called up the camp to come and get them. No civilians were harmed but two POWs were shot dead by a farmer with a shotgun.

There was simply nowhere for them to go – they were immediately recognisable, were lightly dressed, had no food and it was the middle of winter. The last was recaptured nine days later.

Hajime Toyoshima, shown here after his capture in Darwin, is believed to have signalled the start of the revolt. Photo: Australian War Memorial

Others took their own lives. Searchers encountered some grim scenes – 11 were found hanging from trees and two had thrown themselves in front of a train.

McLachlan said for all the carnage of that night, Cowra transformed into a beacon of healing and reconciliation.

In 1960, Japan’s government decided to relocate remains of all Japanese killed in Australia during WW2 to Cowra where those killed in the breakout are interred. In 1971, Cowra proposed creation of Japanese gardens in the town which were developed with the help of the Japanese government and opened in 1979.

This weekend, Cowra will host a number of events marking 75 years since the breakout, with a commemoration timed for 1.50am on Monday, August 5 – when the breakout started – and wreath laying events later in the morning.

-AAP