On Merit: How Paul Keating fixed Labor’s women problem and the Liberals can address theirs

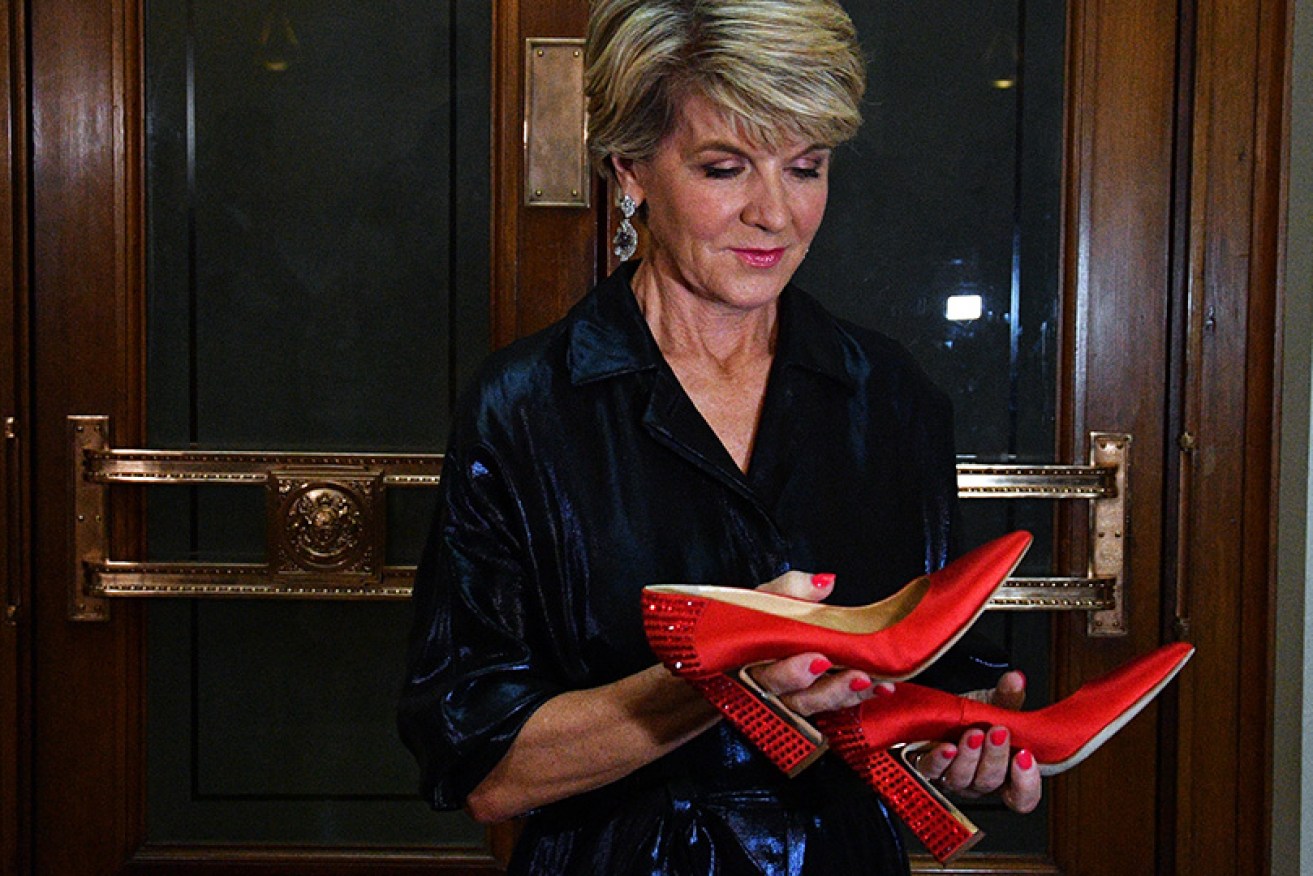

Former Liberal deputy leader Julie Bishop with the red shoes that spurred a movement. Photo: AAP

These days, it’s hard to believe that former Labor prime minister Paul Keating was a turnoff for women. Women voters, that is. Even though the Keating Government was returned at the 1993 election, the proportion of women who voted Labor that year dropped in comparison with men.

While any number of factors could have been the reason, Labor would have taken note that the Australian Election Survey held not long after the poll found that 26 per cent of women rated PM Keating at zero on a zero-to-10 scale of popularity.

That’s even after the PM had made a particular effort to placate the women of Australia by appointing the former head of the Office of the Status of Women, Anne Summers, to help his government develop a suite of policies that would benefit women.

The 1993 result made it clear that female-friendly policies were great, but they weren’t enough. Women in the community also wanted to see Labor supporting women by getting them into parliament.

In 1994, Labor and the Liberal Party had about the same proportion of federal MPs – just less than 15 per cent. Labor came to the realistic conclusion that ambitious Labor men weren’t about to hand over safe seats to talented Labor women out of the goodness of their hearts. So they imposed quotas.

Organisations like EMILY’s List were also created to identify and foster high-quality potential female candidates, so that the quotas would install ‘women of merit’.

Today, women make up 46 per cent of Labor’s federal party room and just 23 per cent of the Liberals’. Opinion polls also suggest that a higher proportion of women than men intend voting Labor at this year’s federal election.

It’s likely that after the election in May, the Liberals will be presented with the same realisation that confronted Labor in 1993. That is, they can’t win without the ‘women’s vote’.

However, Australian women want more than female-friendly policies from a Liberal government; they want to see the Liberals supporting women by getting – and keeping – them in parliament.

Yet without quotas – or some other mechanism to force the male-dominated Liberal Party factions from continuing to appoint men to nearly all the safe seats (not to mention the party leadership) – the number of Liberal women in the House of Representatives could drop to as low as five or six at the upcoming election.

Paula Matthewson’s book On Merit is out on February 5.

Something drastic needs to be done if the Liberals want to prevent sliding into electoral oblivion as the women of Australia desert them.

That drastic action includes denouncing the Liberal Party’s rhetoric about merit. Most Liberal candidates are determined by the party’s factions or leaders, just as they are in the Labor Party. Merit has little or nothing to do with it.

The most recent and stark reminder of that fact is Julie Bishop’s disappointing run for the Liberal leadership in September last year. Scott Morrison did not win the leadership on merit, but because of factional manoeuvring by Liberal men.

Time and again, the hyper-masculine culture of the Liberal Party – brought about by the diminishing number of Liberal women – has ensured the party’s men are predominantly preselected for safe seats, appointed to the ministry, and elected to leadership positions.

But following Ms Bishop’s ‘retirement’ press conference, where she wore those blazing red shoes, Liberal women showed a rebellious streak against that toxic culture that hadn’t been witnessed before.

They called out the bullying behaviour and intimidatory tactics that appear to have become normalised within the party. They even wore the colour red to express solidarity with each other.

The future of today’s Liberal Party could depend on what these women do next. Will they fall into line and continue to reject quotas in favour of the merit myth? Or will they maintain the red shoe rebellion and perhaps even adopt quotas in an effort to rescue the party from the conservative men whose bias against (mostly progressive) Liberal women could drag the Liberals to electoral oblivion?

Paula Matthewson’s first book, On Merit, will be available from 5 February. You can pre-order a copy from most book stores or directly from Melbourne University Publishing.