‘Child protection work is incredibly challenging’: Australia’s child protection services crisis

Experts say there's an ongoing crisis in Australia's child protection services sector. Photo: Getty

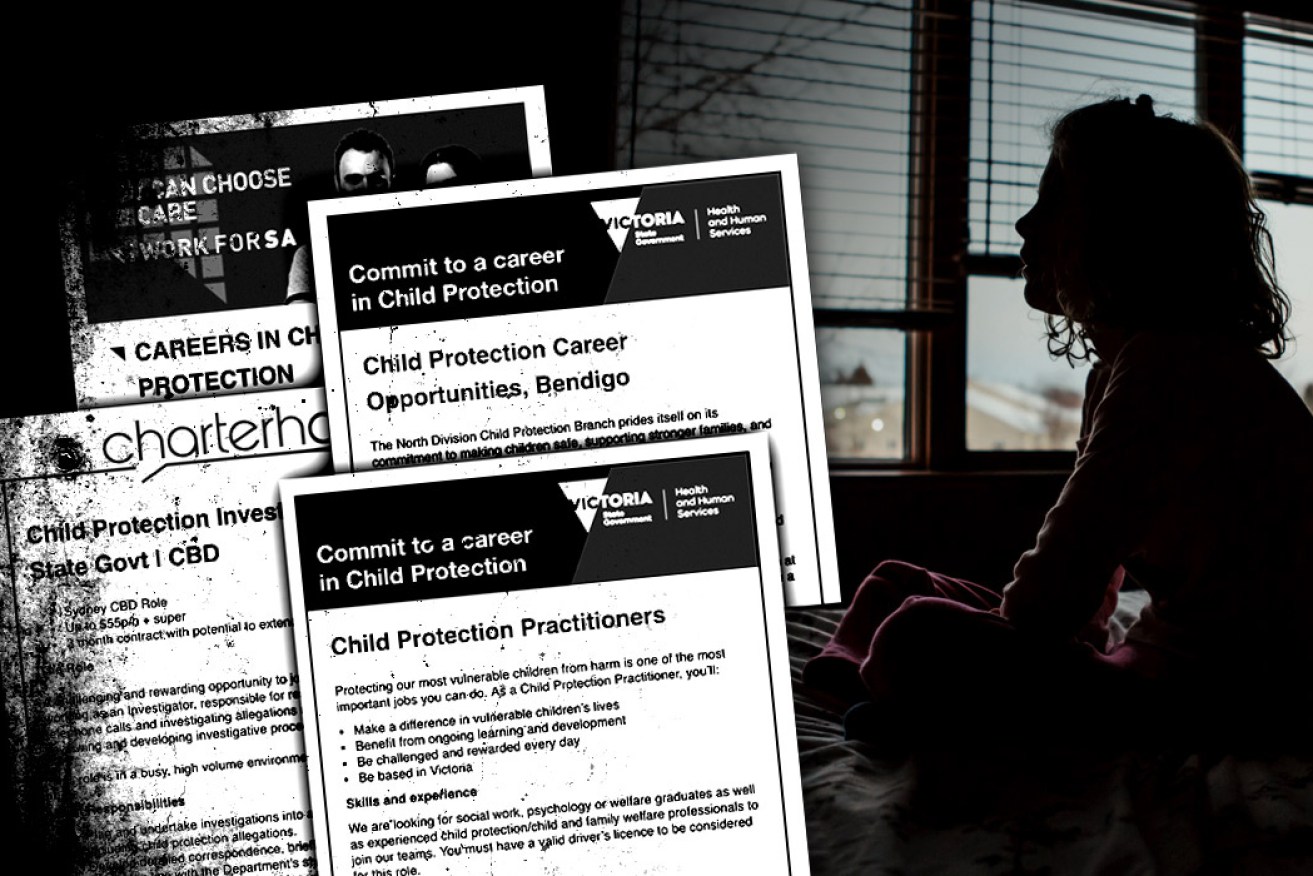

A “crisis” in Australia’s child protection services is forcing government agencies to resort to glossy advertising campaigns and mass hiring sprees in a desperate attempt to attract staff to key frontline roles.

An investigation by The New Daily has revealed child protective services across the country are battling to attract new talent and combat staff attrition in crucial positions.

From the gruesome discovery of a nine-month-old dead baby on a Gold Coast beach this week to the damning findings of the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, there’s a glut of evidence suggesting Australia is in the midst of a child abuse and neglect crisis.

Associate professor in criminology at the University of Western Sydney Michael Salter confirmed Australia’s child protection system is also facing a crisis as staff at the coalface struggle to cope with demand.

“What we know is child protection work is incredibly challenging work and it has a high rate of burnout and staff turnover because staff find the job so difficult,” Dr Salter told The New Daily.

“I’m not surprised that we’re seeing national advertising to try and fill staff placements because it’s a very difficult profession.”

Rising rates rates of child abuse and neglect cases are overwhelming the system, he said.

Last year one out of every 32 children received child protection services, according to an Australian Institute of Health and Welfare report.

Of children receiving child protection services in 2016-17:

- 119,173 were the subject of an investigation looking into allegations of abuse and neglect

- 64,145 were on a care and protection order

- 57,221 were in out-of-home care

Over the five years to 2016-17, the number of official notifications, investigations and substantiations of cases of child neglect and abuse increased dramatically in Australia:

- by 39 per cent for notifications (from 272,980 to 379,459)

- by 45 per cent for investigations (from 122,496 to 177,056)

- by 27 per cent for substantiations (from 53,666 to 67,968)

Government spending on child protection services – including out-of-home care and family support services – rose 8.5 per cent in 2016-17 to $5.2 billion according to a productivity commission report on government services.

According to Dr Salter, however, more needs to be done to support frontline workers and families before the situation becomes critical.

“We need a much better investment in early intervention and family support so that families aren’t at the point of crisis and so we’re not intervening after there has been a critical incident,” he said.

“For as long as [workers] are feeling helpless or powerless to make a real difference, we’re going to continue to see high rates of burnout and turnover.

“The crucial point is that we are waiting too late and there is a lot of nervousness on behalf of governments to put real money into family support and early intervention. And until we do that, then we’re going to continue to face a child protection crisis.”

Desperate times

Western Australia makes its pitch to would-be child protection workers with a slick, purpose-built recruitment website – parts of which read more like a travel brochure than a job advertisement.

“Child protection work is rewarding and fulfilling, but it’s not an easy job,” a role description on the website says.

“Workers need to be confident, resilient, aware individuals, who are open to change, and who can work collaboratively with families and other professionals.

“The department provides great support, career pathways, learning and development opportunities and competitive salary and benefits to our workforce.”

Child protective services job vacancies in WA (November 2018). Source: childprotectioncareers.wa.gov.au

While the department did not respond to The New Daily’s requests for frontline child protection services staff numbers by deadline, its child protection careers site reveals a sprawling list of more than 50 vacancies across 10 offices from Western Kimberley to the Pilbara and Perth.

In 2016-17 Western Australia’s Department of Child Protection and Family Support was contacted more than 85,000 times, with staff carrying out close to 13,000 child safety and wellbeing assessments.

In 2015, The Department of Family and Community Services (FACS) in NSW commissioned former senior public servant David Tune to review its out-of-home care system for children in need.

Immensely critical of the state’s “ad hoc” system, the Tune report was completed in 2016, but remained a secret until June 2018, with Liberal Minister for Family and Community Services Pru Goward accused of trying to “bury the findings”.

Despite this, the report led to a number of reforms, which FACS data shows have not only reduced the number of children being placed in out-of-home care, but have exceeded the predictions made by Mr Tune’s report.

The Department of Family and Community Services (FACS) in NSW employed a record 2203 child protection caseworkers in the 2017-18 financial year, keeping the vacancy rate for these roles at a historically low 3 per cent.

A spokesperson for Queensland’s Department of Child Safety, Youth and Women (DCSYW) told The New Daily it currently employs 1435 frontline child safety staff, comprised of 1148 child safety officers and 287 child safety support officers. And as with other states around the country, it is looking to expand that number.

“The Queensland government is boosting frontline staff and frontline support staff with a staffing increase of 365 full-time equivalent positions over two years from 2016-17 and with a further 93 in 2018-19,” the spokesperson said.

Plagued by scandals

South Australia began a royal commission into the state’s child protection system in 2014 following a series of abuse scandals.

The commission handed down its findings in August 2016, making 256 recommendations to the government on areas including staffing, call centres, child wellbeing practitioners, and ongoing training and best practice.

“The [royal commission report] describes a system in urgent need of reform, pushed beyond capacity and with critical matters slipping through the cracks. The current child protection system fails to tackle a number of interconnected challenges,” the then-Weatherill state government said in response.

In June 2018, the Marshall government released a progress report on the implementation of the royal commission’s recommendations, revealing that 76 of the 256 recommendations had been completed, 113 recommendations are being implemented, 51 recommendations are in the planning stage, and 16 recommendations are yet to begin.

In April, the ABC reported former and current Northern Territory government child protection investigators said the service was failing because staff were being forced to manage caseloads of up to 100 at-risk children.