Why pension reform is terrifying

When Assistant Treasurer Josh Frydenberg raised the prospect of a comprehensive review into retirement incomes last weekend he knew he was opening a big, complex can of worms.

Mr Frydenberg acknowledged that fact when he told Sky News:

“… you can’t look at any of these individual issues in isolation. You have to look at the broader system and how the superannuation system impacts upon the pension and is affected by the tax system.”

So while debate is already raging over the government’s tax reform discussion paper, the Coalition is bravely saying that while everything’s up in the air we might as well look at pensions too. This is admirable, but full of political risk.

• Artful dodgers: how tech giants are playing us for mugs

• Corporate tax avoidance ‘like Islamic State problem’

• Raising the GST will hurt families, say welfare groups

If the Coalition really does want to sort out this tangled mess, it will need a simple message to convince voters it’s doing the right thing because at present Australians seem genuinely confused.

For instance, this week’s Essential Report survey shows that 56 per cent of Australians do not expect the aged pension to be their main source of income in retirement – 25 per cent think it will, and 19 per cent just don’t know. That’s a pretty rosy view of the nation’s private finances, and one not borne out by the Abbott government’s Commission of Audit and the five-yearly Intergenerational Report forecasts.

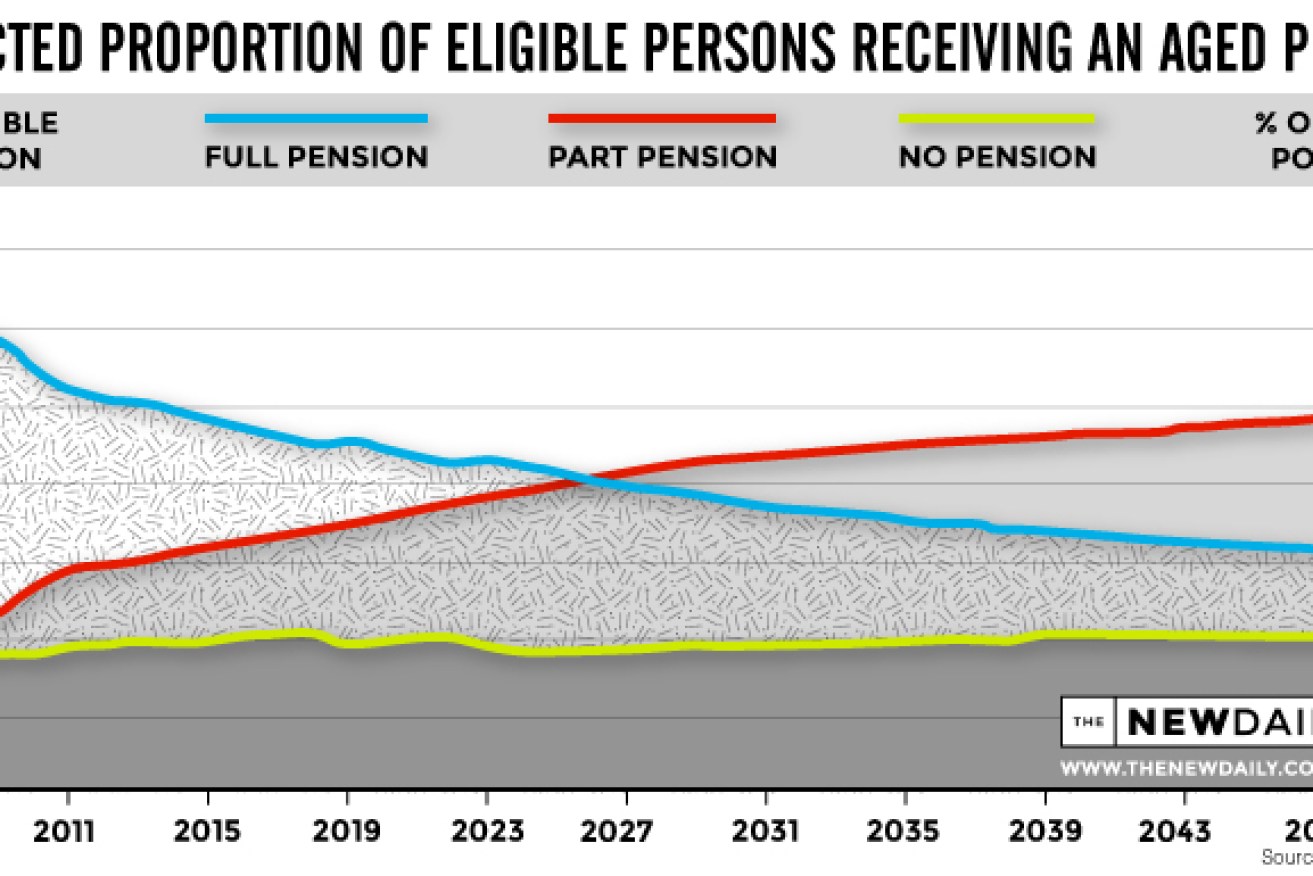

The chart below illustrates that pretty clearly. In 15 years’ time, the proportion of people on a full pension will be around 35 per cent, and another 45 per cent will be on a part pension.

When Labor treasurer Paul Keating set up compulsory super saving in 1991, the aim was to raise contributions over time to 15 per cent of a worker’s income. At that level, the aged pension really would become a safety net for people who for whatever reason didn’t earn much during their work-age years.

But two things went wrong.

First, there was a longevity blow-out. When Keating’s plan was unveiled, men were expected to pop their clogs at 75, and women at 81. Compare that to the 2015 Intergenerational Report forecasts: “In 2054-55, life expectancy at birth is projected to be 95.1 years for men and 96.6 years for women, compared with 91.5 and 93.6 years today.”

The second thing that went wrong was politicians breaking their promises.

Going into the 1996 election, both Keating and Howard promised to raise compulsory contributions from nine to 12 per cent over time. In power, Howard never got around to honouring that promise, and neither did Labor under Kevin Rudd. Only under Julia Gillard did Labor resume the steady increase in compulsory super contributions towards 12 per cent. And even that plan was ‘paused’ by the incoming Abbott government for six years. One has to wonder if there will ever be an increase above the current 9.5 per cent.

But given all of that, let’s get back to the real story of the relationship between pensions, super, and taxation.

A hell of a lot of the complexity around these issues could be solved if firm targets were set for three things: the pension, which should be the minimum required for a dignified but frugal life in old age; the level of super savings that taxpayers should help one achieve for a more comfortable retirement; and the level above that at which your personal wealth doesn’t need a leg-up from fellow Australians at all.

The first is pretty simple. Both Labor and the cross-bench senators have refused to budge on the existing way of adjusting pensions for inflation, which effectively maintains the full pension at 28 per cent of average male earnings. The Coalition wanted that figure to be lowered over time, but the political hurdles to such a change are enormous – so let’s take the current system as a given.

The second, ill-defined benchmark, is what level of super you need to be incentivised to accumulate so as to take you off the pension altogether. This level is currently stated in absolute terms – that is, as the value of your assets, minus your family home (again, politically difficult to include in means testing) that allow you to still claim a part pension.

At the moment the cut-off is $1.1 million for couples which implies a tax free income of just over $50,000. If that doesn’t sound like much, remember that average full time weekly earnings across the economy is currently $76,800, taking home just $60,300. Some groups, such as the Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS) want to see the asset test tightened, so that couples lose their part pension when they are holding assets worth just under $800,000. The Greens look likely to support that kind of tightening, though it must be said that the Coalition would be very brave indeed to revise means testing so dramatically.

But even if that $1.1 million threshold were left in place, the final question to ask of the tax/super/pension system is how much should other taxpayers be giving in the way of tax concessions for people retiring with much more than that cut-off?

Actually, it’s a stupid question. Why should a young working family pay a cent more tax than necessary to allow a wealthy retiree to receive concessional tax rates on earnings within their super fun (15 per cent ) and zero per cent on distributions from that fund? There is no good answer to that question from left or right.

That’s why ACOSS, the Greens, the Commission of Audit, the Murray review – you name it – all think a total overhaul of the system is needed to return the incentives and concessions to middle income earners and stop ladling them out to the wealthy.

Just which side of politics can get that through without being booted out of office at the very next election is the real question.