Malcolm Fraser: a political giant

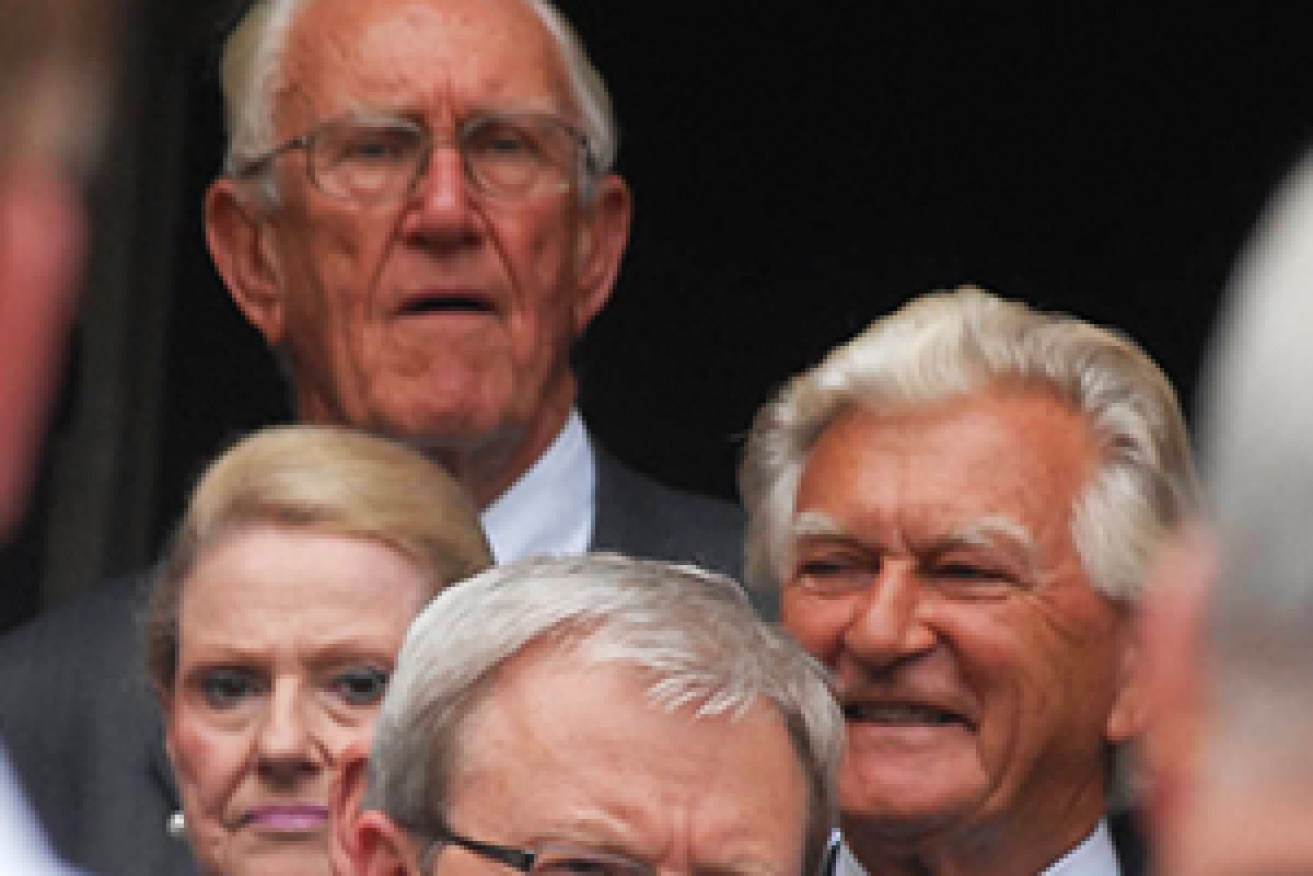

Malcolm Fraser stood out both politically,and physically. Photo: AAP

By any measure Malcolm John Fraser was a giant.

He, along with Gough Whitlam and Sir John Kerr, will be forever remembered for the earthquake of the 1975 dismissal, during which he displayed the resolution and toughness of the partisan politician.

He had the numbers in the senate and his opponent Labor’s Gough Whitlam had given him every excuse to use them.

• Former PM Malcolm Fraser dead at 84

• Six ways Malcolm Fraser changed Australia forever

• In pictures: Malcolm Fraser’s life and career

Few could disagree that the loans affair was “reprehensible” – an Australian government prepared to use a dodgy Pakistani money man outside the purview of the loans council.

No one could blame him for blocking supply, while many are less forgiving of a duplicitous governor general who did not deal frankly with the duly elected prime minister.

Those arguments still divide, but now that the last actor of that crisis has departed they will lose much of the bitterness of the past forty years.

Indeed, one of the legacies of the sacking of the Whitlam government was the emergence of a consensus that the Senate should not act in that way again.

To ensure this, the electorate has developed the habit of voting one way for the House of Representatives and another for the Senate.

But Malcolm Fraser’s method of victory forever tainted his term in office, even though he won overwhelming support at the ballot box in the two following elections and a handsome victory at his third.

Fraser, despite the emotions he aroused at the time, was no right wing ideologue.

Malcolm Fraser towered above history, and many of his political peers. Photo: AAP

His government was cohesive and middle of the road. He was fiscally conservative but socially inclusive. He resisted the urging of business and party conservatives to take on the industrial relations club and deregulate financial markets.

This frustrated the more militant right wingers because he had control of both houses of parliament for two terms. His reluctance to go down the path of a ‘Workchoices’-style assault on the unions had more to do with his sense of fairness than anything else.

In December 2009 he quit the Liberal Party of which he had been a member for sixty years, claiming it was no longer liberal but conservative. His anger was spurred by the rolling of moderate Malcolm Turnbull and his replacement by the right wing warrior Tony Abbott.

Just five weeks ago, he told ABC radio that it is Abbott who should resign rather than Human Rights Commission President Gillian Triggs.

He was first and foremost a humanitarian who rejected racism and was a champion of the oppressed. For example, he enacted Whitlam’s proposed Northern Territory Land Rights Act.

I have fond memories of him talking to a group of us journalists at a reception in Kuala Lumpur in 1989 during the Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting. Bob Hawke was backing him to be Secretary General of the organisation. After a while he ended the conversation saying “there are no votes here” and walked off to unsuccessfully schmooze delegates.

Malcolm Fraser had a vision of a big and generous Australia. He successfully settled 100,000 Vietnamese refugees during his time as prime minister. He like many others lamented the demise of that compassion as evidenced by our treatment of boat people.

Vale an Australian giant.