Should the world be more open to Russia’s Sputnik V COVID-19 vaccine?

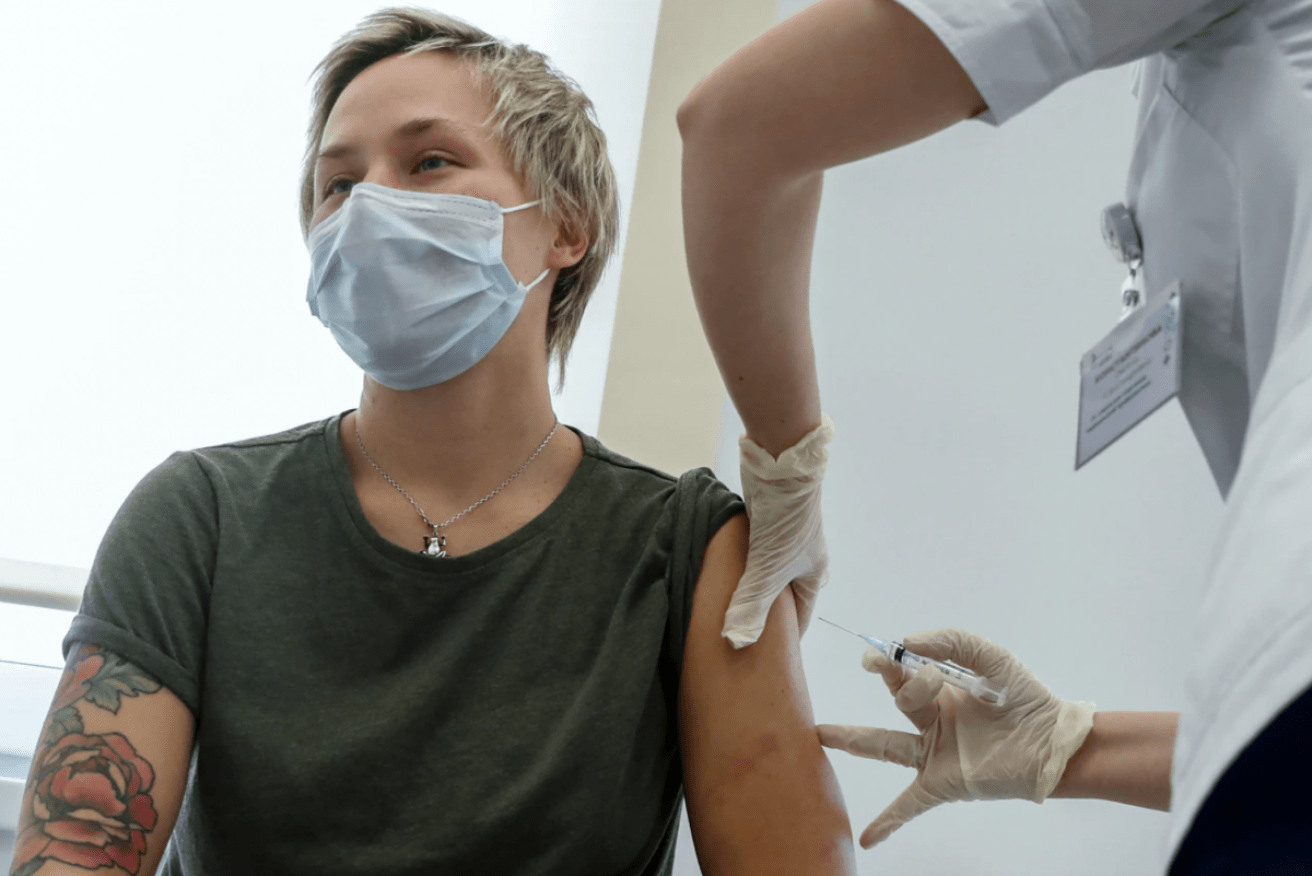

The Sputnik V vaccine was first approved in August last year and rolled out in Russia in December. Photo: AP

Russian President Vladimir Putin should have had his first dose of a locally made COVID-19 vaccine by now.

The Kremlin announced he would be vaccinated by the end of Tuesday, Russian time.

Yet the president, who is ordinarily not afraid to pose shirtless for the cameras, won’t be getting his jab publicly.

“As for vaccination under the cameras, [Putin] doesn’t like it,” his press secretary Dmitry Peskov told reporters.

The Kremlin declined to say which vaccine Mr Putin would receive, but Mr Peskov insisted it would be Russian-made.

“All three Russian vaccines are absolutely reliable and effective,” he said.

Russia has granted emergency approval for two locally made vaccines, EpiVacCorona and CoviVac.

However, Russia’s ‘Sputnik V’ is by far the most promising.

The vaccine was widely criticised during its development for a rushed rollout and “questionable” early data.

However, Sputnik V is proving to be a success.

Now, as European nations scramble to secure enough vaccines, some of Russia’s staunchest critics are considering using Sputnik V as well.

Russia’s vaccine was treated with suspicion

Russia’s vaccine is a source of national pride.

The name Sputnik V invokes memories of the space race during which Russia was pitted against the West. Sputnik was the name of a Russian satellite — the first launched by any nation into orbit.

The pace with which Russia approached the COVID-19 vaccination race triggered alarms bell around the world.

Russian President Vladimir Putin received his first dose of an unknown COVID-19 vaccine on Tuesday. Photo: AP

When Mr Putin announced the vaccine had been approved in August, before stage three human trials had been completed, he was accused of recklessness by many scientists.

The news that the president’s daughter had been given a jab did little to alleviate their concerns.

Ian Jones, a professor of virology at the University of Reading, said the scientific community’s early scepticism was understandable.

“The early suspicions about the development of the vaccine were that they were too fast and that there wasn’t enough data,” Professor Jones told the ABC.

By November, Russia had started vaccinating thousands of troops before the results of large-scale trials had been published.

“It suggested that there was some sort of dodging going on,” Professor Jones said.

However, he said the results of stage three trials tell a different story.

“This is clearly not the case,” he said.

“Whatever they chose to do beforehand is now swept away by the actual data from the phase three trial.”

Sputnik V boasts 92 per cent efficacy

The results of stage three human trials published in the Lancet, demonstrate efficacy of 92 per cent percent.

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine boats 95 per cent and the Oxford-AstraZeneca team reported 70 per cent efficacy based on pooled data.

A US trial of the AstraZeneca vaccine, published this week, suggested efficacy of 79 per cent and total protection against severe disease.

However, US health officials later suggested outdated information may have been used.

Professor Jones said that while he’d already received an AstraZeneca jab, he would have no reservations about getting the Sputnik V vaccine.

“I would certainly take it,” he said.

The Sputnik V vaccine works in a similar way to the AstraZeneca product.

It uses a modified version of a common cold-like virus as a “vector” to harmlessly introduce part of the coronavirus’s genetic code to the body.

This allows the immune system to recognise and fight the coronavirus, even without a previous infection.

Russia began vaccinating doctors, teachers and others in high-risk groups with Sputnik V in December last year. Photo: AP

However, Sputnik V uses different versions of these vectors in the first and second doses, which are given 21 days apart.

Professor Jones said it might give the vaccine a slight advantage.

“What this is supposed to rule out, is the fact that the first shot can raise immunity that might stop the second shot,” he said.

“It’s a theoretical concern more than a real concern, but it’s the only vaccine that does that.”

“The others use the same thing again and again.”

However, it requires two different versions to be produced which may complicate the rollout, he said.

The Russian government says more than 6 million people have received at least one dose of a vaccine, but a recent poll suggested 60 per cent of Russians don’t want the Sputnik V.

According to figures compiled by Our World in Data, Russia has administered six doses for every 100 people.

Germany has administered 13 doses per 100 people, the UK 45 per 100 and Australia just 1.4 per 100.

European nations turn to Russia

The Sputnik V is already being used in dozens of countries across the Middle East, Africa, Asia and South America.

Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro received the Sputnik vaccine earlier this month, joking that he could speak Russian after the shot. Photo: Twitter

However, its growing acceptance in the European Union is exposing divisions and threatening the bloc’s coordinated approach to vaccine procurement, which has struggled to secure enough doses for member states.

Slovakia and Hungary have already taken deliveries of Sputnik V, bypassing the European Medicines Agency which has placed the vaccine under a “rolling review”.

Austria and the Czech Republic have also expressed an interest in using it.

And there are plans to start producing the vaccine in Italy later this year.

“Despite the deliberate discrediting of our vaccine, more and more countries are showing interest in it,” Mr Putin said this week.

Relations between the EU and Russia are at low point due to disputes over aggression in Ukraine, cyberattacks on European institutions and the poisoning of Russian opposition figure Alexei Navalny.

Earlier this month, EU Council President Charles Michel publicly questioned Russia’s motives, accusing it of running “highly limited by widely publicised” foreign vaccination campaigns which he said amounted to “propaganda”.

But the Kremlin said on Monday that Mr Michel and Mr Putin spoke about the possibility of using Russian vaccines in Europe.

Even Germany – an outspoken critic of Russia – says it would be prepared to purchase the Sputnik V.

“I am actually very much in favour of us doing it nationally if the European Union does not do something,” German health minister Jens Spahn said last week.

However, the EU’s Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton dismissed suggestions Europe needed Russia’s assistance.

“We have absolutely no need for Sputnik V,” he told French television station TF1.

“It’s a strange statement,” Vladimir Putin replied.

“We’re not imposing anything on anyone.”

-ABC