The aged-care crisis is not black and white – but we could learn a thing or two from Nan

My Nan was the grandmother every family deserves.

No Michelin chef could match her pavlovas. No therapist could match her comforting arms. And no scientist could ever disprove her theory that eating cheese before bed causes nightmares.

She was a woman who shone light into the lives of everyone she met. Yet her last few years were spent in a world of shadows and encroaching darkness.

Nan was 95 when she passed away in an aged-care facility; tired, frail, virtually blind and comforted only by the sound of a radio and the voices of constantly visiting family.

We hated seeing her this way.

She hated it, too. It hardly seemed a blessing that her hearing and mind remained sharp.

She heard every nursing home alarm. She knew the squeaking of trolley wheels outside her room meant the death of another resident.

Yet my grandmother was also lucky. In a nation where our treatment of the elderly is becoming increasingly scandalous, she was in a home that was run professionally and where the carers showed kindness and patience.

This week the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety heard how operators of a Queensland nursing home removed computer records, furniture and beds before bothering to call emergency services to have 68 elderly residents evacuated in ambulances.

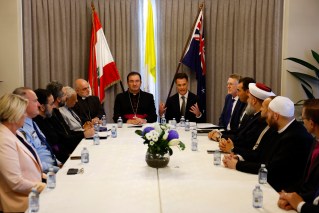

Garry with his beloved grandmother, Norma, who died two years ago. Photo: Linnell family

The inquiry, which is due to deliver its interim report later this year, has already heard an appalling series of stories about neglect and mistreatment in our aged-care industry.

Not that any of us are numbed or surprised.

But the commission’s recommendations may be our last chance to improve what is now nothing less than a national disgrace.

Our failure as a society is exposed in the photographs of microwaved frankfurt sausages served on stale bread, the constant examples of dementia sufferers left unattended for days in soiled beds, and the seemingly endless instances of physical, mental and chemical abuse.

Of course, we blame the government and regulators for decades of failure. But really, we are all failing.

How a society treats its elders – particularly its frailest and most vulnerable – reflects its values and empathy.

Can anyone recall the last time thousands gathered in the streets to demand greater care for those who gave us what we have today?

Would you eat this? The ABC gathered photos of food in aged care homes. Photo: ABC

The question confronting all of us is how we devise a way of coping with the coming wave of older Australians living longer lives.

It’s a complicated issue, but part of the solution lies in the more immediate dilemma facing the royal commission – how best to look after the infirm and helpless in our community.

Our current method, which has operator profit at its heart, clearly does not work.

The future, as if you didn’t know already, is completely grey.

In the mid-1960s almost one in two Australians were aged under 25. Within a few decades almost one in four of us will be over 65.

Many of us will continue working well past that age – and enjoy greater quality of life because of rapidly improving medical care.

Well, those of us who can afford to fund their retirement …

But there will be hundreds of thousands of us who will not get to enjoy the life depicted in those glossy brochures for aged care residential villages. You know the type – silver-haired couples clinking cocktails over candlelit dinners or smiling under blue skies on the golf course.

Many of us will instead go the way of my grandmother – beyond the care of immediate family and requiring ongoing medical care.

Think retirement will look like this? Think again. Photo: Getty

The royal commission does not have to look far for possible solutions.

The Japanese, who boast the world’s oldest population and its healthiest, are driven by the spectre of ubasute – the mythical practice of abandoning an elderly relative on a mountain top to die from dehydration or exposure to the elements.

Social changes have forced more Japanese couples to work full-time and abandon the traditional method of caring for ailing grandparents at home.

So for the past two decades, increased taxes on the wealthy and higher co-payments have ushered in a generational-changing care insurance scheme.

It has had its problems and placed enormous strain on the economy, but it has also defied widespread expectations of failure.

Other nations like the Netherlands have devised successful methods of providing greater care for dementia sufferers while reducing the pressure on nursing staff.

My Nan was a keeper of sayings and family lore; a bridge between eras who had grown up on a farm without electricity, walked to school for miles in bare feet, lowered food into a deep well to keep it cool and – in later life – managed to produce enormous family banquets on the barest of pensions.

Perhaps because of this she was also extraordinarily stubborn.

It ended up becoming a physical trait. Her body simply refused to surrender. The nurses who cared for her said they had never seen anything like it.

Right now we all need some of her doggedness and stoicism.

All of us – not just the royal commission – need to persevere and find a way to manage this growing crisis.

It won’t be easy. But if we don’t, you can forget those idyllic glossy brochures promoting retirement villages around the country.

Australia, instead, will become nothing more than a village of the damned.