World-first study links exercise and life expectancy for those with heart defects

Testing the limits for people with half a heart: Dr Derek Tran and Sarah West at work on the new study.

Until the 1980s, many children with congenital heart defects died in the first months of life, and those who survived to adulthood tended to be wrapped in cotton wool along the way.

There was fear that putting a young person under any strain, such as exercise or playing sport, might cause damage or even kill them.

Until recently, that advice was given to young people born with structural defects, where functionally a child had only half a heart to keep them going.

Exploring the limits

That approach has changed, and many young people, threatened lifespan notwithstanding, are chasing after as much life and adventure as they can.

Sarah West, 26, is one of these people.

Recently, she signed up to a world-first exercise trial – run by the Heart Research Institute (HRI) – that hopes to improve the life expectancy of those born with congenital heart disease.

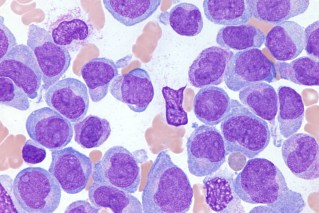

The two major arteries of Sarah West’s heart were connected to the right ventricle.

“I signed up because I wanted to know what I was really capable of,” Sarah said.

“Until now I’ve always been too scared to find out my full potential.”

Sarah’s story

Sarah, from Campbelltown in New South Wales, was born with a rare congenital heart defect known as Double outlet right ventricle (DORV).

This is where the pulmonary artery and the aorta – the heart’s two major arteries – were both connected to the right ventricle.

At 18 months Sarah had a shunt inserted to help the heart grow.

At the age of eight, she underwent open heart surgery.

Sarah underwent open heart surgery when she was eight.

“I was a member of the zipper club,” she said.

“Being a little older, I remember it well. We just didn’t know what the future would hold for me.”

Sarah West has explored the world, but didn’t know how far she could push her body.

At school, she played representative baseball and netball, but “I could never play soccer or do cross country”.

Although there were limitations, “they never stopped me travelling the world”.

Sarah is in her last year of a Masters degree in speech pathology and will be busy in the months ahead with placements and clinical exposure to patients.

The exercise trial

Sarah recently began the exercise trial, which she discovered online.

For the next four months, three times a week, she’s undergoing progressive weight-resistant training under the supervision of HRI exercise physiologists.

“Previously I was always using light weights,” she said. “I didn’t know what I could safely do. On a leg-press machine I’d only do 30 kilos.”

But at an early session, where she was taught how to use the machines and tested for maximum effort, Sarah pushed 130 kilograms.

“I wasn’t doing reps, just seeing what the maximum I was able to do,” she said. “I was so surprised and happy.”

From here on, “we’ll actually start much lower and built it up over time”.

Participants needed

Dr Derek Tran, senior exercise physiology fellow with the Heart Research Institute, is the co-ordinator of the trial.

The exercise program “will look at whether aerobic and resistance training can improve heart function, lung growth, fitness, and ultimately life expectancy for people with congenital heart disease”, Dr Tran said.

Dr Derek Tran is co-ordinator of the trial.

The trial was about improving the quality of life for participants, he said.

“It’s also about giving people the confidence of knowing they can exercise on their own,” he said.

So far 40 people have signed up for the trial in NSW.

The researchers want to recruit 400 participants between the ages of 10 and 55 years of age, from across the country.

Why it’s important

Eight babies are born every day in Australia with congenital heart disease (CHD).

This refers to a suite of problems with the heart’s structure. These can lead to abnormal heart rhythms, blue-tinted skin, shortness of breath, difficulty feeding and/or swollen body organs.

Serious cases occasionally require a heart transplant.

Leading HRI cardiologist Associate Professor Rachael Cordina said emerging research suggests exercising could be more important for people with even the most complex types of CHD, because it has special effects on the circulation.

“People living with half a heart have no heart pump to push blood up through the lungs, so they rely heavily on the exercising muscles in the body – but there is hardly any research to understand the true impact of exercise on these special circulations and how to safely implement exercise training,” Associate Professor Cordina said.

If you’re interested in signing up to the Congenital Heart Fitness Intervention Trial (CH-FIT), please see here.