Feeling paranoid? It goes with the times we’re living in

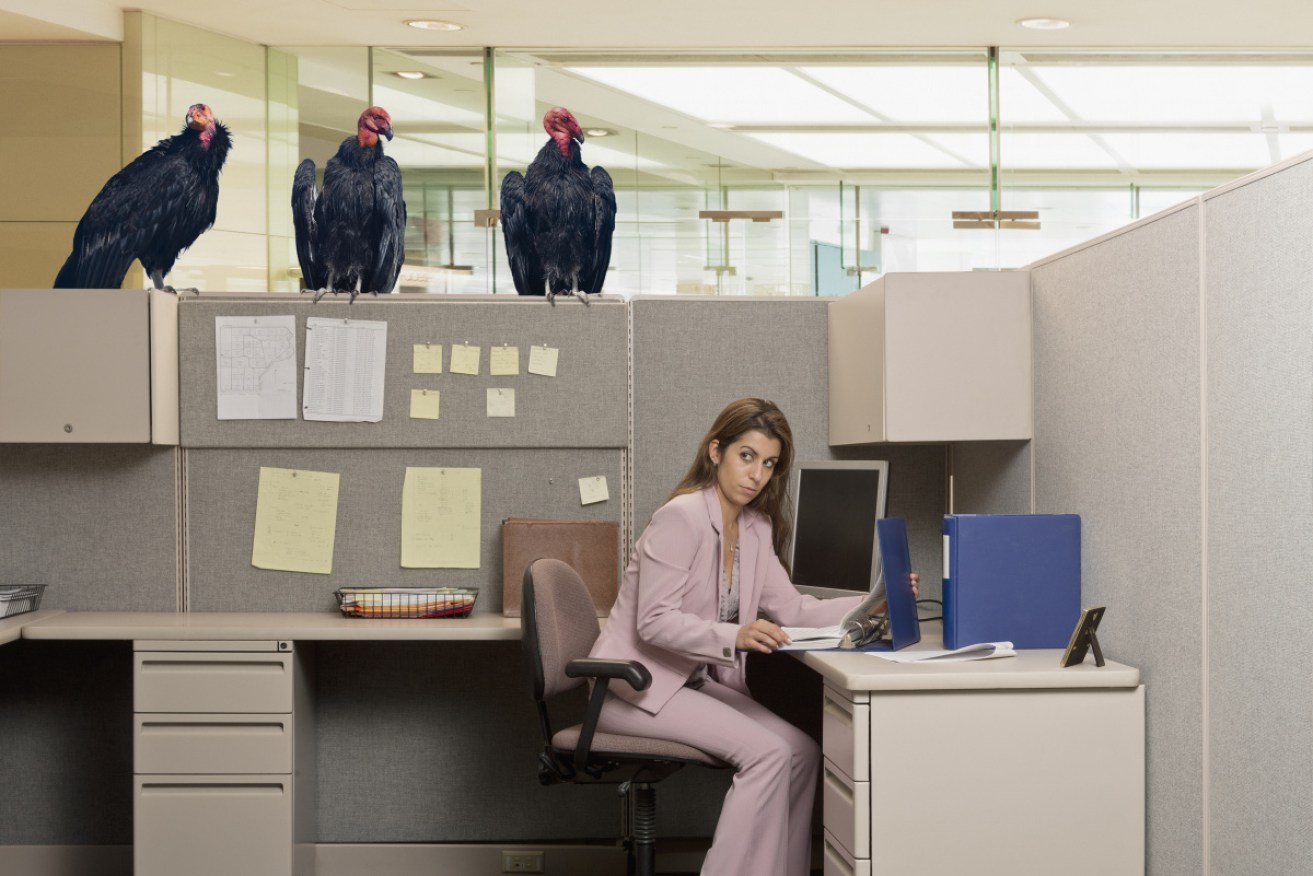

Feeling the world is out to get you? One in five people routinely feel this way. The rate goes up when there's greater uncertainty. Photo: Getty

New research from Yale University suggests that when society is rocked by unexpected uncertainty – as we are now, with the COVID-19 pandemic – ordinarily healthy people become vulnerable to paranoid thinking.

“When our world changes unexpectedly, we want to blame that volatility on somebody, to make sense of it, and perhaps neutralise it,” said Dr Philip Corlett, associate professor of psychiatry and senior author of the study, in a prepared statement.

“Historically in times of upheaval, such as the great fire of ancient Rome … or the 9/11 terrorist attacks, paranoia and conspiratorial thinking increased.”

Maybe we’re all on a paranoiac continuum

Paranoia is generally cast as a symptom of serious mental illness. But episodes of paranoia – a state of mind marked by “the belief that other people have malicious intentions” – are relatively common in the general population.

For instance, a previous study found that one in five people believed people that somebody was against them at some time during the past year. Nearly one in 10 believed that others were actively out to harm them in some way.

And one in 50 believed there was a plot “to cause them serious harm.”

In that 2010 research, found various socio-economic factors were associated with paranoia, but also “stress at work, less social cohesion, less calmness and anxiety.

A 2009 study from Kings College London found a strong link between sleeplessness and persecutory thoughts. Indeed, “general population individuals” with insomnia were five times more likely to have high levels of paranoid thinking than people who were sleeping well.

Not to make you paranoid, but … how are you sleeping through the COVID crisis?

A new theory

The prevailing theory is that “paranoia stems from an inability to accurately assess social threats,” the Yale researchers say.

But in this new study, they hypothesise that paranoia is “instead rooted in a more basic learning mechanism that is triggered by uncertainty, even in the absence of social threat.”

Erin Reed is lead author of the paper, and PhD candidate at the Yale School of Medicine.

“We think of the brain as a prediction machine. Unexpected change, whether social or not, may constitute a type of threat – it limits the brain’s ability to make predictions,” she said.

“Paranoia may be a response to uncertainty in general, and social interactions can be particularly complex and difficult to predict.”

How did they reach this conclusion?

According to a statement from the university, the researchers conducted a series of experiments that essentially played with the minds of participants who were assessed to have “different degrees” of paranoia.

- The subjects played a card game in which the best choices for success were changed secretly.

- People with little or no paranoia were slow to assume that the best choice had changed.

- However, those with paranoia expected even more volatility in the game. They changed their choices capriciously – even after a win.

- The researchers then increased the levels of uncertainty by changing the chances of winning halfway through the game without telling the participants.

- This sudden change made “even the low-paranoia participants behave like those with paranoia, learning less from the consequences of their choices.”

Even animals can be driven crazy by these experiments

In a related experiment, rats were trained to complete a similar task where best choices of success changed.

Rats who were administered methamphetamine – known to induce paranoia in humans – “behaved just like paranoid humans.”

They, too, anticipated high volatility and relied more on their expectations than learning from the task.

A mathematical model was used to compare choices made by rats and humans while performing these similar tasks. The results from the rats that received methamphetamine resembled those of humans with paranoia, researchers found.

“Our hope is that this work will facilitate a mechanistic explanation of paranoia, a first step in the development of new treatments that target those underlying mechanisms,” Dr Corlett said.

Paranoia can be a self-fulfilling prophecy

A 2012 study found that work-place paranoia about negative gossip or being snubbed leads people to seek out information to confirm their fears. This ultimately annoys colleagues and increases the likelihood they will be rejected or subverted.

How to avoid such a trap?

“It may be best to ignore impulses that tell you that you’re the victim of office politics,” the University of British Columbia researchers advised.

They noted that it’s natural for people to wonder how others view them.

“However, our research shows employees should do their best to keep their interactions positive and ignore the negative. As the expression goes, kill them with kindness.”

One last thing

Just in case you’re scoffing at the idea that rats can be made paranoid, consider this 2011 study from the University of Liverpool.

The researchers found that male fruit flies experience a type of paranoia in the presence of another male.

This causes them to double the length of time they mate with a female, “despite the female of the species only ever mating with one male.”