The search for alien worlds is about to get much closer to home

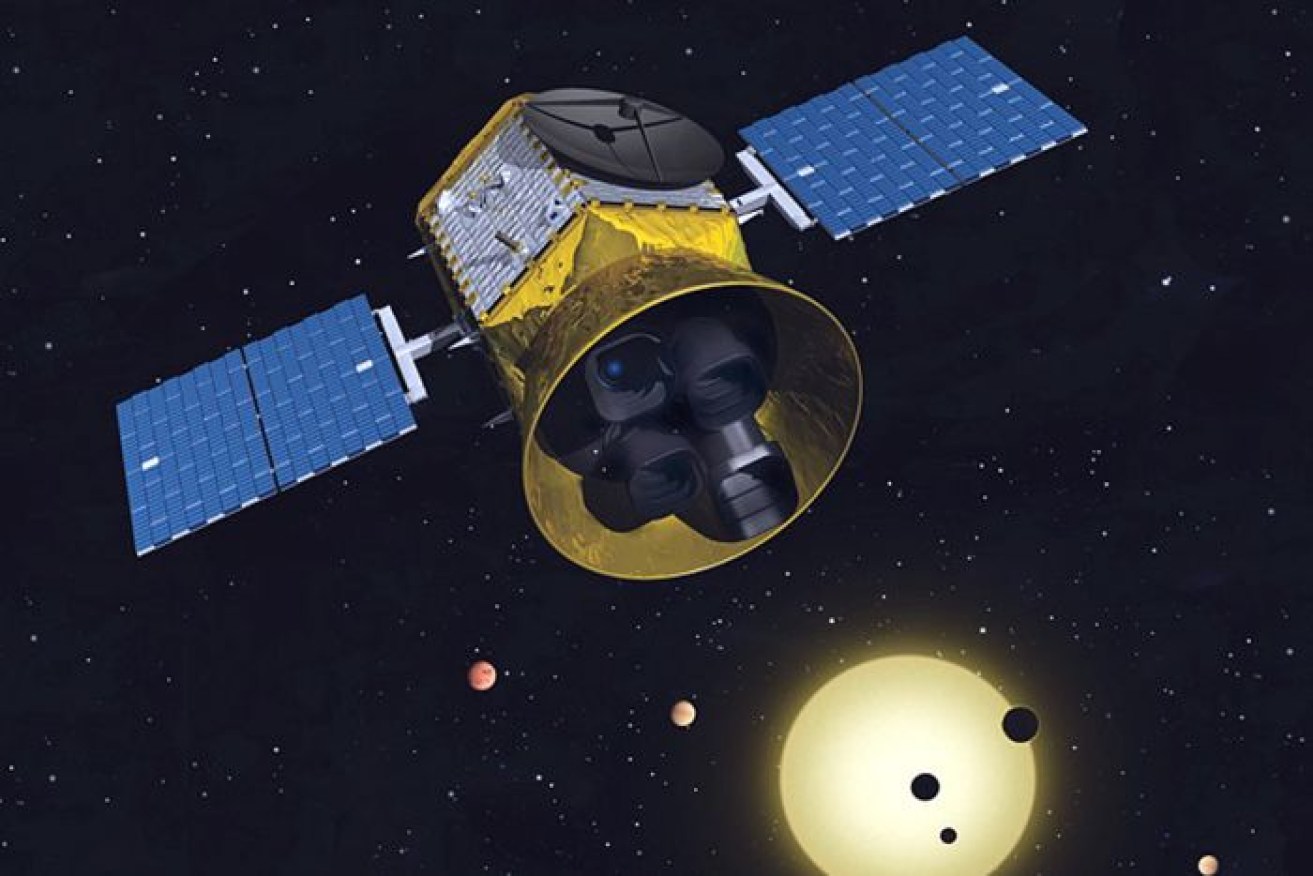

Astronomers hope the Transiting Survey Satellite (TESS) will find at least 20,000 new alien worlds. Photo: MIT

Just a decade ago, we had no idea whether worlds with qualities like our own blue planet existed around other stars in the Milky Way.

That all changed with the launch of the Kepler space telescope in 2009.

At last count NASA’s planet finder has helped identify 2400 alien planets of all sizes, including entire solar systems, orbiting faraway stars.

“It’s changed our view of planets, it’s changed our view of our solar system and how common exoplanets are out there,” Brad Tucker of the Australian National University said.

But even though Kepler has discovered a swag of planets, we still know very little about alien worlds because most of the ones we’ve found are too far away to be easily studied by ground-based telescopes for hints of life.

NASA’s new planet hunting telescope promises to change that.

The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS for short, is set to be launched at 8:30am AEST this Tuesday from Cape Canaveral.

“It’s going to be a discovery machine,” Dr Tucker said. “Our number of exoplanets is going to go through the roof.”

How to spot an alien next door

George Ricker, from the Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is leading the mission.

TESS will find planets that ultimately we hope will be reasonable targets for interstellar probes in the future,” Dr Ricker said.