DNA sampling could determine if Tasmanian tigers exist, researcher says

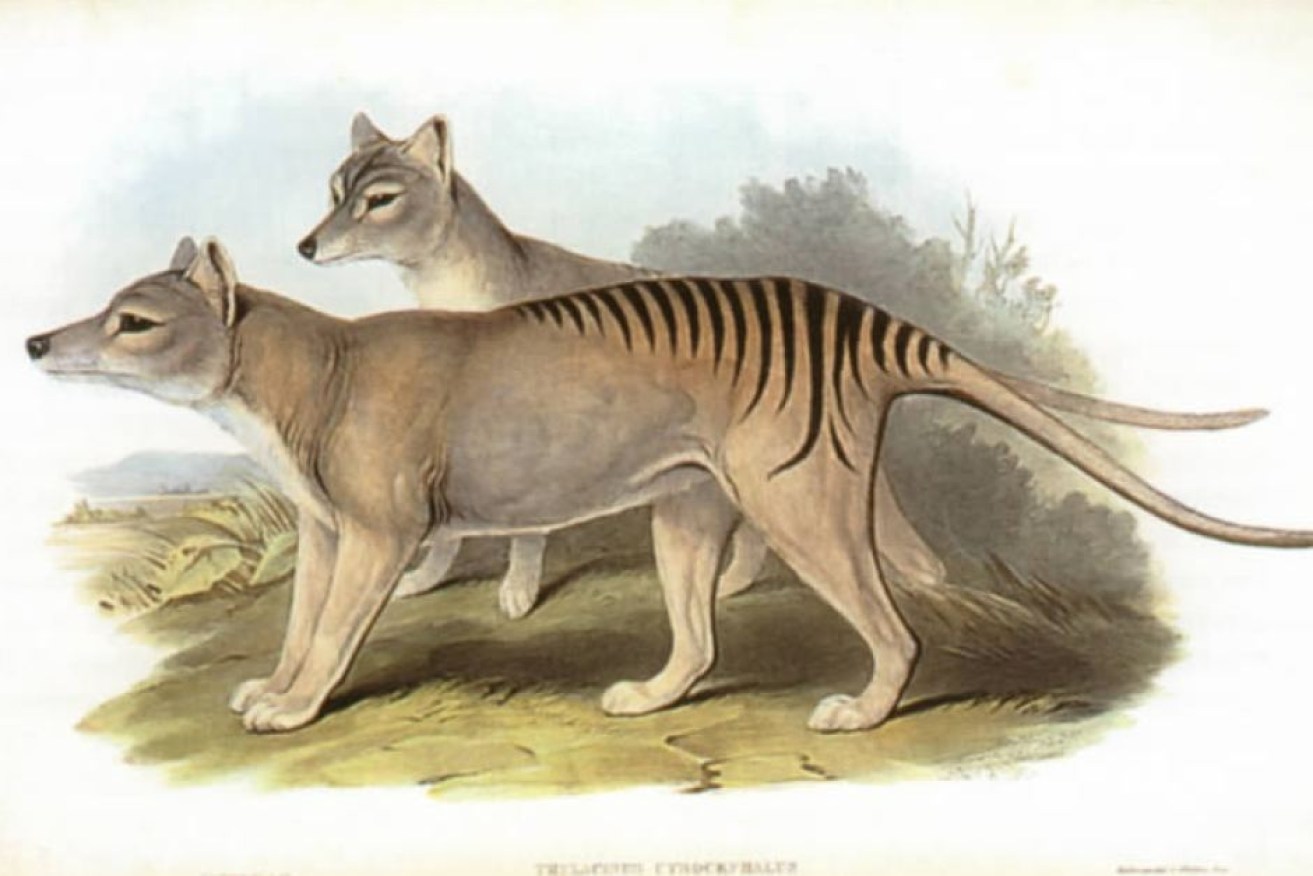

It turns out much of we thought we knew about the Tasmanian tiger simply isn't true. Photo: Wikimedia Commons: John Gould

Modern forensic science could be used to solve the mystery around the existence of the Tasmanian tiger, a lab researcher says.

Reports have regularly emerged of people who say they have seen one, with grainy photographs often presented. But now it is thought DNA sampling could help to provide a conclusive answer.

Tasmanian tiger enthusiast Col Bailey has spent much of his life trying to prove the thylacinus cynocephalus – which roughly translates as “pouched dog with a wolf’s head” – is still alive and at large.

He has written a number of books on the subject and maintains he saw one in southern Tasmania in 1995.

Bailey said it was in the Weld River Valley, near a creek among thick bushland.

“I went to walk towards it and it backed back, and then it turned a full circle and turned around and stood glaring at me,” he said.

“It snarled, with a hiss, and that stopped me dead in my tracks and then the penny dropped and it dawned on me that it was a Tasmanian tiger.”

Other than his own recollection, Bailey has no proof of the sighting, but new DNA sampling being conducted in South Australia to aid in a platypus hunt could provide a way of verifying similar encounters.

Senior manager of laboratory services for Australian Water Quality Centre, Karen Simpson, said if a tiger had either drunk or walked through a water sample, its DNA could be identified.

“We do have the DNA of the thylacine in our database,” she said.

“If there has been a Tasmanian tiger out there and we collect the sample that captures the DNA, we’ll be able to determine positively if it’s present or not.”

Danger DNA samples could dilute

Wildlife biologist Nick Mooney spent 30 years investigating many of the tiger sightings that had been reported to the Tasmanian government.

He said the DNA water testing technology could have helped him verify evidence, such as a cast of footprints from 2010.

“Somebody gave me a cast of some footprints that they claimed were taken near Lake Pedder,” Mr Mooney said.

Benjamin, the last thylacine in captivity, died at a zoo in Hobart in 1936. Photo: Wikimedia Commons: David Fleay

“I can’t vouch for them because I didn’t record them, all I can vouch for was that someone gave to me claiming they’re from there.”

Lake Pedder, in south-west Tasmania, is part of the largest dam and water storage system in Australia, and Ms Simpson said there was a risk any potential DNA could float away.

“Because it’s such a large water body, the issue becomes, I guess, dilution,” she said.

“You would really need to try and pinpoint what point of that body or lake (the thylacine) was interacting with to try and collect your samples from around that area.”

Ms Simpson said the best type of water to test in would be a small pond, meaning there was still a large chance any proof of living thylacines could slip away.

-ABC