Almost missed it: Citizen scientists discover rare new planet

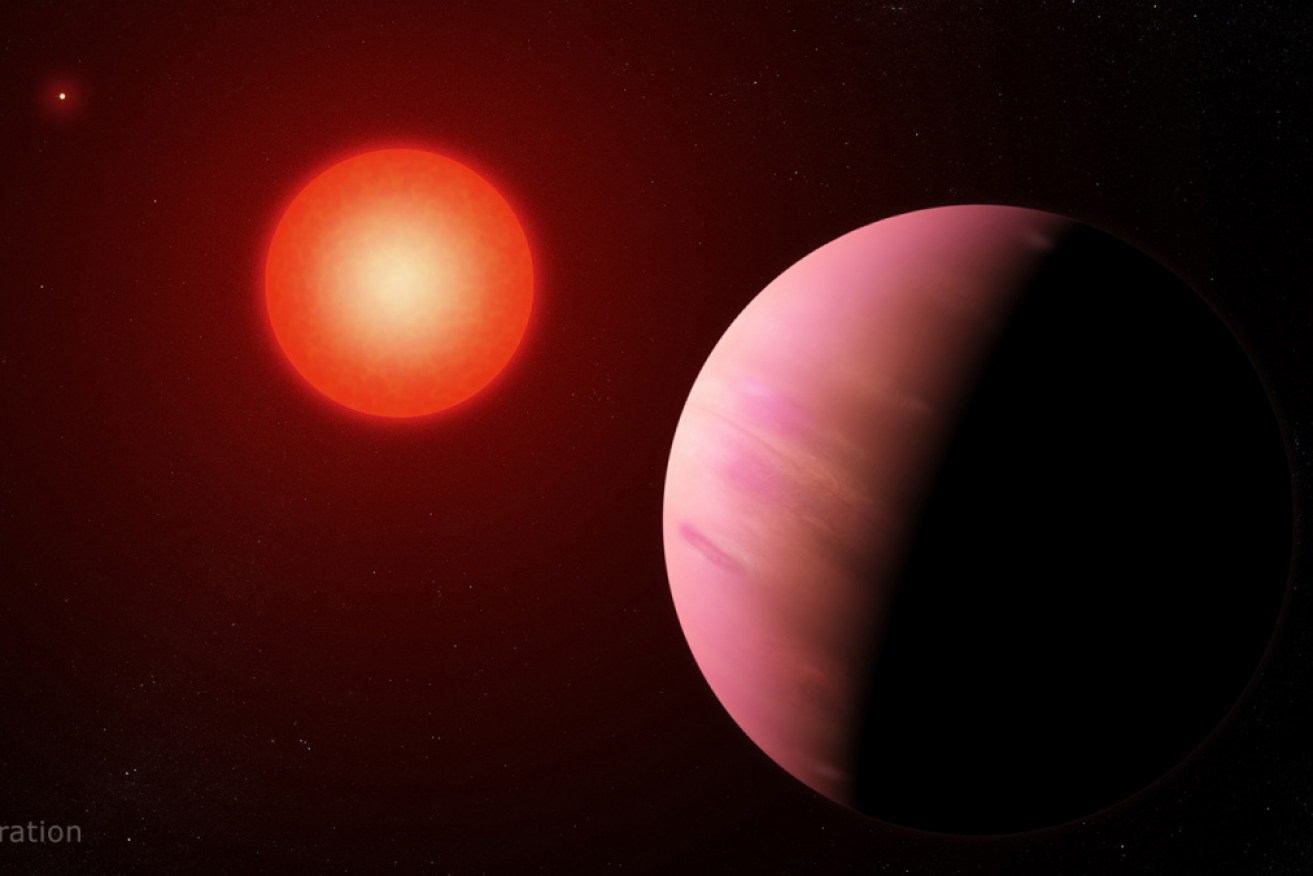

Almost twice the size of Earth, the new planet sits in the habitable zone of its star, a small red dwarf in the constellation Taurus. Illustration: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center/Francis Reddy

Citizen scientists have discovered a new planet using data from NASA’s Kepler telescope – information that the professional astronomers had initially disregarded as unreliable and not worth examining.

The new planet, known as K2-288Bb, is almost twice the size of Earth, and sits within its star’s habitable zone – close enough to contain liquid water on the surface, but not so close as to have it evaporate as steam.

It was found 226 light-years away in the constellation Taurus – and is possibly a rocky planet or rich with gas, like Neptune. It’s a rare find, because few planets of its size have been found to occupy an orbit that could sustain life.

A rare find … in the way it was found

“It’s a very exciting discovery due to how it was found, its temperate orbit and because planets of this size seem to be relatively uncommon,” said Adina Feinstein, a University of Chicago graduate student and lead author of a paper describing the new planet accepted for publication by The Astronomical Journal.

She was speaking on Monday at the 233rd meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Seattle.

According to a statement from Nasa’s Jet propulsion laboratory at the California Institute of Technology, the planet lies in a stellar system known as K2-288, which contains a pair of dim, cool M-type stars – commonly known as long-living red dwarfs. The stars are separated by about 8.2 billion kilometres, roughly six times the distance between Saturn and the Sun.

The brighter star is about half as massive and large as the Sun, while its companion is about one-third the Sun’s mass and size. The new planet orbits the smaller, dimmer star every 31.3 days.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about the planet is how it was discovered.

Dodgy data was discarded

Two years ago, Adina Feinstein and undergraduate student Makennah Bristow were working as interns with NASA astrophysicist Joshua Schlieder – with the cool job of looking for planets.

They did this by searching Kepler telescope data for evidence of transits, the regular dimming of a star when an orbiting planet moves across the star’s face.

They found two transits suggesting the existence of a planet, but needed evidence of a third transit to confirm the discovery. They couldn’t find it.

By this time, Kepler was on its K2 mission, which ran from 2014 to October 2018, when it ran out of fuel and essentially died. During the K2 mission, the spacecraft carrying the telescope repositioned itself to search a new patch of sky every three months.

The problem was, repositioning the spacecraft caused tiny changes in the shape of the telescope and the temperature of the electronics – and these systematic errors rendered the first few days of data in the new spot unreliable.

So the data was discarded – including that containing evidence of the third transit.

They fixed the data, but failed to look it over

To deal with this, early versions of the software that was used to prepare the data for planet-finding analysis simply ignored the first few days of observations – and that’s how the third transit went missing.

Eventually, the astronomers learned how to correct for these errors and the data during repositioning was kept, but the early K2 data remained on the scrapheap.

Joshua Schlieder, a co-author of the paper, says in the NASA statement: “We eventually re-ran all data from the early campaigns through the modified software and then re-ran the planet search to get a list of candidates, but these candidates were never fully visually inspected.”

Inspecting, or vetting, transits with the human eye is crucial because noise and other astrophysical events can mimic transits.”

And this is where the citizen scientists come into the story. The re-processed data wasn’t investigated by the Kepler project, but rather posted to Exoplanet Explorers, a project where the public searches Kepler’s K2 observations to locate new transiting planets.

In May 2017, volunteers noticed the third transit, setting off much excited discussion – which in turn caught the attention of Adina Feinstein.

“That’s how we missed it – and it took the keen eyes of citizen scientists to make this extremely valuable find and point us to it,” Feinstein told the conference.

The existence of the new planet was confirmed by follow-up observations using NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, the Keck II telescope at the W. M. Keck Observatory and NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility and data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission.

This is the seventh planet that citizen scientists have helped discover.