From witchcraft to mosquitoes: The mystery of flesh-eating ulcers solved

Flesh-eating Buruli bacteria needs to be diagnosed early. For one woman it took four months.

The mystery, for scientists, began in the late 19th century, when a missionary physician named Albert Cook described necrotising skin ulcers in patients in Uganda.

Some were more disabling than others.

This was the first evidence of the flesh-eating Buruli ulcer (BU), as caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium ulcerans.

From the 1960s, cases of the disease were reported from 20 additional African countries, where the major burden commonly falls on children aged five to 15 years.

According to a historical review of research and treatment, causes of BU disease “are commonly perceived by the local population as somewhat mysterious and are often associated with witchcraft or sorcery”.

But it’s also perceived that “insect bites, contamination of skin lesions, and contact with swamps and water bodies often connected with changes in ecology are considered risk factors for contracting BU”.

In other words, there’s an idea that a Buruli ulcer is a consequence of both natural and darkly magical agents.

The early stages of case study Sharm Dunlop’s infection. Photo: Supplied

This leads many African patients to first consult traditional healers or prayer camps to deal with the witchcraft side of things. And only then do they seek treatment at hospitals or health centres.

This explains why too many Africans turn up at hospitals with advanced large lesions. These often result in permanent disabilities.

Australians seeking treatment too late for a Buruli ulcer, in first-world hospitals, have suffered similar outcomes.

The painful mystery confronting Sharm Dunlop

In late June, Sharm Dunlop thought she’d been bitten by a spider, maybe a white-tail. She’d been bitten by white-tails before and the red, raised wound on her thigh looked familiar.

Sharm Dunlop didn’t get a correct diagnosis for four months.

“It looked like a red bite and I didn’t think much of it,” she told The New Daily. “But it started to form a head, like you get on a pimple. Then the skin started to go necrotic … and it got bigger and bigger.”

So she went to a GP, because it was getting painful. “They gave me some antibiotics and said I should be fine.”

Four times she returned to her doctor, because the infection, on the back of her right thigh, was getting worse, despite the antibiotics.

By late August, Sharm Dunlop couldn’t walk, couldn’t work.

“It had become quite infected.”

Her partner’s mother was a nurse.

“I asked her to have a look. She thought I had severe cellulitis. I went to the hospital and was admitted there.”

The hospital put Sharm on IV antibiotics and drained the wound, thinking it was an abscess.

“Another two months went by and it still hadn’t healed,” she said.

In October, she went to a specialist who took a biopsy around the site. Finally, she was diagnosed with a Buruli ulcer, and was on three months of antibiotics, two doses.

And how is it now?

“I have to wear a patch every day because it’s still not healed. I need to see an infectious disease physician because it seems to be getting worse. And I think I will have to get antibiotics again.”

The most frustrating part of this saga, she said, was not getting an accurate diagnosis for four months. And the doctors she saw were on the Mornington Peninsula, on Port Philip Bay.

Why is this significant? Because it’s where you’re more likely to develop a Buruli ulcer. It’s where doctors are more likely to see them.

This week, science came up with answers

Two questions have mystified Australian scientists for decades.

The first: How does the Buruli bacteria ulcer enter the body? That one has been a mystery since the discovery of the Mycobacterium ulcerans bacterium, by Australian scientists, in the 1940s.

Secondly: How did this flesh-eating bacterium found in tropical West Africa become endemic on the Bellarine and Mornington Peninsula in Victoria?

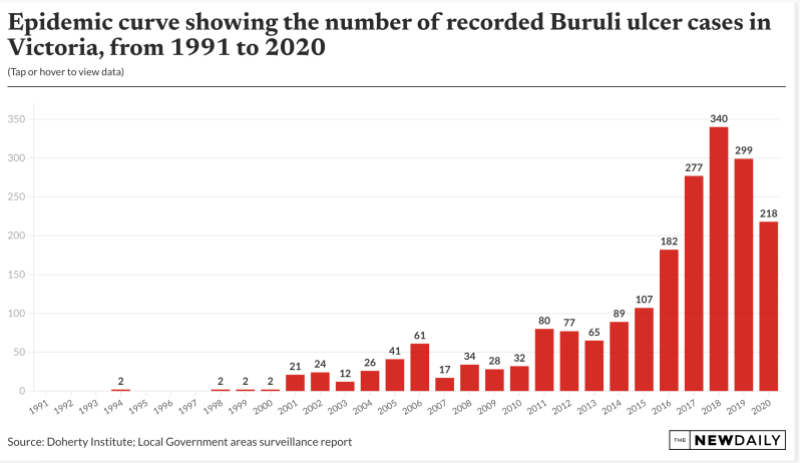

Since the turn of the century, there has been, as Doherty Institute scientists describe it, “an alarming and inexplicable surge in cases in and around Melbourne and Geelong”.

In the past decade, annual cases in Victoria have increased by 1000 per cent – with affected people often left with significant cosmetic, and sometimes functional, damage to limbs.

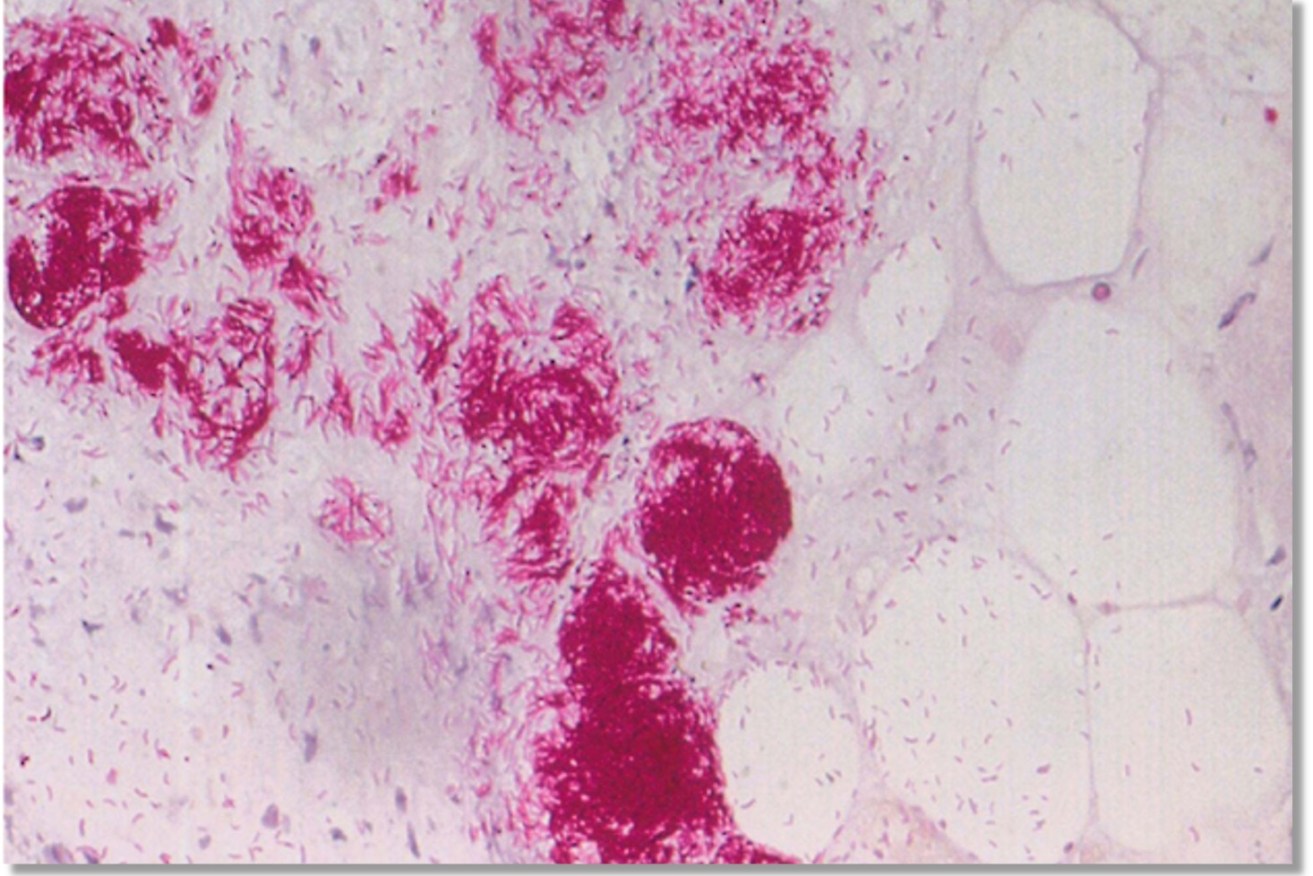

Buruli ulcer is an infection of the skin and soft tissue by Mycobacterium ulcerans. The bacteria’s toxins attack fat cells under the skin, causing redness and swelling or the formation of a nodule (lump) and then an ulcer.

This week, scientists from the Doherty Institute and partners announced “a major breakthrough” as to what’s driving the surge.

The evil agent is the mosquito.

The reservoir of the bacteria, from which the mosquito sups, is the possum.

How did they find this out?

The project is led by University of Melbourne’s Professor Tim Stinear, director of the WHO Collaborating Centre for Mycobacterium ulcerans at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity.

The skin around Sharm Dunlop’s wound turns necrotic. Photo: Supplied

Published in Nature Microbiology, the team’s findings “categorically confirm mosquitoes as the primary vectors transmitting the ulcer-causing bacteria Mycobacterium ulcerans from the environment to people”.

The paper actually details how mosquitoes provide a transmission route between possums and humans, at least in bayside suburbs.

Focusing on the Mornington Peninsula, the project team trapped and tested more than 65,000 mosquitoes between 2016 and 2021.

Possums a factor

Since the inception of the study in late 2018, Stinear and his team systematically collected possum faecal material from across the Mornington Peninsula.

Antibiotics from a GP were no help to Sharm Dunlop.

They collected possum poo from more than 2000 sites between Portsea and Rosebud and tested these samples for Mycobacterium ulcerans.

“We are showing the clear, positive correlation between areas where possums are carrying the bacteria and humans are getting Buruli ulcer,” Stinear said.

The Beating Buruli in Victoria project includes researchers from the Bio21 Institute, Agriculture Victoria, Austin Health, Victorian Department of Health, the Mornington Peninsula Shire, CSIRO and others.

What the scientists say

Professor Stinear said: “How Buruli ulcer is spread to people has baffled scientists and public health experts for decades.

“So now that mystery is solved with our five-year study revealing that mosquitoes transmit (the bacteria) in south-eastern Australia, making mosquito bite prevention and mosquito control obvious forms of prevention.”

Dr Peter Mee, research scientist at Agriculture Victoria and one of the lead authors of the paper, described how forensic-level genomics were deployed: “Thanks to genome sequencing, we discovered that the genetic make-up of the bacteria M. ulcerans in mosquitoes was identical to that found in Buruli ulcer patients in the study area.”

He said this was “a key part of a compelling body of evidence pointing to mosquitoes as the transmission link”.

Dr Katherine Gibney, an infectious diseases and public health physician and one of the study leads at the Doherty Institute, said it was important to maintain wildlife and mosquito population monitoring:

“Maintaining this type of mosquito surveillance work could offer crucial insights into the epidemiology of Buruli ulcer in the region and inform public health interventions aimed at controlling the disease.”

Facing scepticism

Professor Paul Johnson, infectious diseases physician at Austin Health said the team had faced difficulties convincing others that mosquitoes were spreading Buruli ulcer.

“We long suspected mosquitoes were involved, but there is no precedence for a bacterial infection like Buruli ulcer being transmitted this way,” he said.

But the team “faced considerable scepticism, so we gathered irrefutable evidence to support our claim”.

Within a couple of months Sharm Dunlop couldn’t walk.

Further to this, Professor Johnson explained: “It is unusual for mosquito to transmit bacteria. Some other research mention that some subspecies of the bacterium Francisella tularensis, which causes tularaemia, have been found to be spread by mosquitoes in Scandinavia. However, Mycobacterium ulcerans is a mycobacterium, not an intracellular gram negative pathogen … This research is the first time that evidence shows that a mycobacteria can be transmitted this way.”

He said the research was significant “because we can all take simple actions, like applying insect repellent and removing stagnant water around the house, to protect the community and reduce the risk of Buruli ulcer”.

The Beating Buruli in Victoria team is new running a trial aimed at reducing mosquito populations in urban areas. Specifically: Brunswick West, Pascoe Vale South, Moonee Ponds and Essendon in Victoria, using state-of-the-art, environmentally friendly mosquito traps.