New-look Oprah: Her prescription weight-loss drug explained

Oprah Winfrey has lost weight slowly and sensibly over the past two years. Photo: Getty

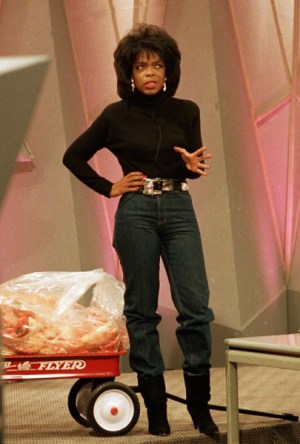

Back in 1988, for four months between seasons of her TV show, Oprah Winfrey ate nothing. That is, nothing that could be chewed.

She walked on to the stage of her talk show pulling a wagon loaded with 30 kilograms of fat – the amount of weight she’d lost by sticking to an all-liquid protein diet.

Dressed in a pair of much-loved size-10 Calvin Klein jeans, the star turned this way and that like a catwalk model, while the audience hooted and hollered.

Gosh. She’d really done it. Become sort of skinny. Clips of slim Oprah were played everywhere. However, in a short amount of time, the weight was back on, with some extra.

That was 35 years ago – and since then Winfrey’s weight has gone up and down, as she’s tried different strategies.

Has she finally cracked the code?

In the past year, a new class of drugs, primarily for treating type 2 diabetes, but found to be effective for weight loss, was fanatically adopted by chubby TikTok mums.

And boy, did the word get around.

Oprah Winfrey in 1988.

Their enthusiasm sparked a world-wide shortage, left many diabetics in the lurch – and launched a wave of speculation as to which (suddenly skinny) Hollywood stars were using these new drugs.

Meanwhile, Winfrey has dropped 20 kilograms over two years, since knee surgery.

She said the weight loss was a consequence of drinking a gallon of water, a lot of walking, and eating her last meal (healthy foods only) of the day at 4pm.

She’s now turning 70 years old. She looks very healthy, more than she did after drinking all that liquid protein decades ago.

This week, she confessed that she was, in fact, also using a prescription medicine, as a strategy to prevent her weight from yo-yoing.

She’d resisted this, she said, while reportedly recommending the drugs to friends.

She hasn’t named the drug but it is almost certainly semaglutide, marketed as Wegovy in the US, and Ozempic in Australia.

Where did these drugs come from?

US researchers trumpeted a new drug as a “game changer” in the management of obesity – and for once, a large, gold-standard clinical trial backed up the hype.

A single weekly injection of the drug semaglutide, for 68 weeks, saw an average loss of 15 per cent body weight in trial participants.

Those given a placebo, in tandem with a diet and exercise program, lost 2.4 per cent of their body weight.

Ozempic’s manufacturer is spending millions to ramp up production. Photo: Getty

More than a third of the participants who took the drug lost more than 20 per cent of their weight.

This prompted the ordinarily sober New York Times, citing the researchers, to write: “For the first time, a drug has been shown so effective against obesity that patients may dodge many of its worst consequences, including diabetes.”

As experts told the NYT, these results far exceeded the amount of weight loss observed in clinical trials of other obesity medications.

The drug is a “game changer,” said Dr Robert F Kushner, an obesity researcher at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, who led the study.

“This is the start of a new era of effective treatments for obesity.”

How does it work?

Semaglutide mimics a natural hormone called GLP1 – or glucagon-like peptide 1.

GLP1 is a gut hormone that is released in response to undigested food hitting the distal small bowel. Drugs mimicking the hormone make you feel full faster and longer.

At the same time, as your blood sugar levels rise, in response to you eating, GLP1 – and drugs such as semaglutide – trigger the body to produce more insulin. This helps lower blood sugar levels. This is why semaglutide is so useful for diabetics.

And it’s important to reiterate that semaglutide was primarily developed as a treatment for diabetes. Sustained weight loss protects against the disease progressing too quickly.

But the drug was hijacked by social media.

The controversy

Once the drug was approved – in the US and then Australia – a version of the Hunger Games ensued, with diabetics competing with overweight people to get prescriptions.

Within a few months of the drug being launched, there were localised shortages that blew out to global shortages.

In November last year, after GPs were advised to stop prescribing Ozempic off-label – advice that many doctors seemed to ignore – the Therapeutic Goods Administration warned social media influencers to stop promoting prescription medicines.

The ‘influencers’ in question were mainly overweight mums in pyjamas and slippers, and less of the high-profile glamorous persuasion.

The TGA warned these alleged pyjama-wearing influencers they were risking “jail time” – and criminal penalties of up to $888,000 for individuals and civil penalties of $1.1 million.

But the horse had well and truly bolted.

Meanwhile, the global market for novel weight-loss drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy is “poised to reach $100 billion by 2035 as patients start to understand the efficacy of the medications”, Fortune reported in September.

Common side effects

The most commonly reported side effects of Ozempic include:

- Abdominal pain

- Constipation

- Diarrhoea

- Nausea or vomiting.

Serious side effects

According to Healthline, serious side effects of Ozempic can include:

- Diabetic retinopathy (damaged blood vessels in the eye)

- Gallbladder disease, including gallstones or cholecystitis (gallbladder pain and swelling)

- Kidney problems

- Pancreatitis (swelling of the pancreas)

- Increased risk of thyroid cancer

- Allergic reaction

- Hypoglycemia (low blood sugar).

The US Federal Drug Administration (FDA) has put a boxed warning on Ozempic for an increased risk of thyroid cancer.

In July, the European Medicines Agency began investigating started GLP-1 treatments after reports of suicidal thoughts and self-harm from people who had been taking the anti-obesity drugs.

In September, the FDA ordered that Ozempic labelling include a warning about the potential to develop blocked intestines. This is a potentially fatal condition.

Drugs like semaglutide cause muscle loss, a side effect countered by exercise.

Muscle loss

Ozempic and other drugs mimicking GLP1 cause muscle loss.

According to one report, much of the weight loss resulting from GLP-1 agonists “is the loss of muscle, bone mass, and other lean tissue rather than body fat”.

What needs to be kept in mind, and GPs are no doubt aware of this, is that drugs like semaglutide are meant to be used in tandem with a healthy diet and exercise regime.

People who do weight training will be better at maintaining their bones and muscle, as well as their metabolism.

Ozempic face

One of the emerging horrors for Hollywood stars using Ozempic is an older, saggier face – nicknamed ‘Ozempic face’ by a US doctor.

An exaggeration yes, but losing weight tends to age the face. Photo: Getty

It’s a natural and common consequence of weight loss, especially in middle-aged people. As we age, and work to lose weight, we can end up looking gaunt.

The answer? Unfortunately, fillers or even surgery are required to fix your face while maintaining your new body.

A piece in The New York Times, detailing the horrors of ‘Ozempic face’, quoted the great French actor Catherine Deneuve: “At a certain age, you have to choose between your face and your ass.”

Finally, once you’re on semaglutide, it’s probably for life.

Participants in that 2021 trial rejoiced at their weight loss. But once they stopped taking the drug, the weight came back.

The same holds for Winfrey.