The Stats Guy: How Australia’s ‘business model’ guarantees our wealth into the future

Welcome to the last column in our five-part mini-series about the next 10 years in Australia.

What the future holds for a country very much depends on broader global developments and the viability of the national business model.

In Australia we create wealth by doing four things very well: Mining, agriculture, international education and tourism. That’s it. That’s what we export.

That’s how we achieve a positive trade balance and bring foreign capital into our country.

Our simplistic but lucrative national business model guarantees a continuation of the high migration approach, slows efforts of economic diversification, and delivers general wealth and prosperity (at least as soon as we fix housing).

In the next 10 years, will our national business model continue to work?

Let’s start our analysis by looking at global population data.

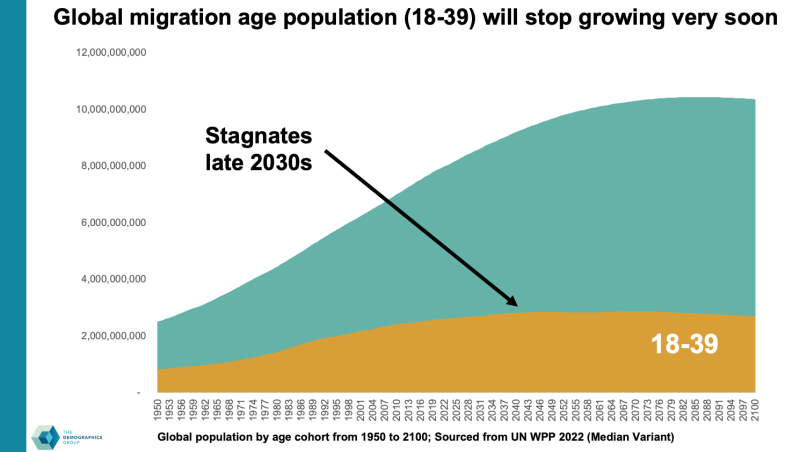

Depending on who you listen to, global population will peak in 40 to 60 years, global working age population will peak 20 years before that, and population of migration age (18 to 39) will already stagnate by 2033. This suggests that global competition for migrants to balance out ageing demographics and shrinking workforces will intensify.

We might already be in the last decade where countries charge visa fees.

Free visas and even financial incentives will be the norm – at least for migrants whose skills are in demand. Easy global mobility is guaranteed for healthcare workers, tradies and highly skilled knowledge workers.

For the next decade we might take it for granted that we will find enough international migrants to fill our local skill gaps and attend our universities.

From the late 2030s the global source of migration-aged people will be so narrow that countries across the globe will be in strong competition to attract young talent. Continuing our migration-driven economic model will get harder from 2033.

Not all migration is voluntary though. Poverty, hunger, and war drive involuntary migration. These three drivers improved massively over recent decades. There is less poverty, less hunger and fewer war deaths now – even though the omnipresence of these issues in the news might mislead us into thinking the opposite was true.

In the coming decades climate change will be a major driver of involuntary migration. Whole regions will become barren as desertification intensifies, and they will become less liveable as heat and the frequency of extreme weather events intensifies. This will force many to pack up and seek a better life elsewhere – often they will not be welcomed with open arms.

The migrant waves across the Mediterranean that Europe experienced in the past decade will pale in comparison to what is to come. This global increase in involuntary migrants will affect European nations severely while Australia will hardly be impacted at all.

There is a fine line between the tyranny of distance described by Geoffrey Blainey (where Australia is too far removed from economic opportunities) and having a strong moat (Australian borders are easy to control). By sheer geographic dumb luck Australia will largely avoid having to deal with involuntary migration in the coming decade. That gives us a relative advantage compared to regions that must tackle these issues head on – like all of Europe.

The national business model

As mentioned above, we make money by selling four things to the world – mining products, agricultural products, international education and tourism. I would expect demand and prices for all four of our main exports to only go up in the next 10 years.

Mining will receive a complete image makeover very soon.

Our biggest industry is shifting in the public eye over next 10 years from an evil, dirty polluter to a green industry empowering the electrification of the global transport network. In the era of the combustion engine, you only needed steel and oil. That was easy enough.

Now that we will electrify the global transport network, we need about eight mining products to produce a car battery. These mining products aren’t evenly distributed across the globe and precious few can be found in stable democracies where the rule of law is guaranteed. Australia is one of the exceptions.

Not only will there be elevated demand for our mining products, but we can also guarantee supply much better than a kleptomaniac dictatorship can. In a world where the US will increasingly step back from its role as global police force guaranteeing maritime security, supply chain sovereignty will be a bigger issue.

Our biggest trading partners are the three Asian powerhouses of China, India and Japan.

Between them they will find a way to ensure that ships can travel safely between ports. Remember that we are a double net exporter of food and energy while China as a double net importer is very dependent on a global network of trading partners.

As climate change impacts agriculture, rising global food prices will hit the bottom two billion people on the planet particularly hard. As a net exporter of food Australia stands to benefit here too.

Food will get much more expensive in the coming decade. Our local challenge will be to increase agricultural output while experiencing extreme weather events more frequently.

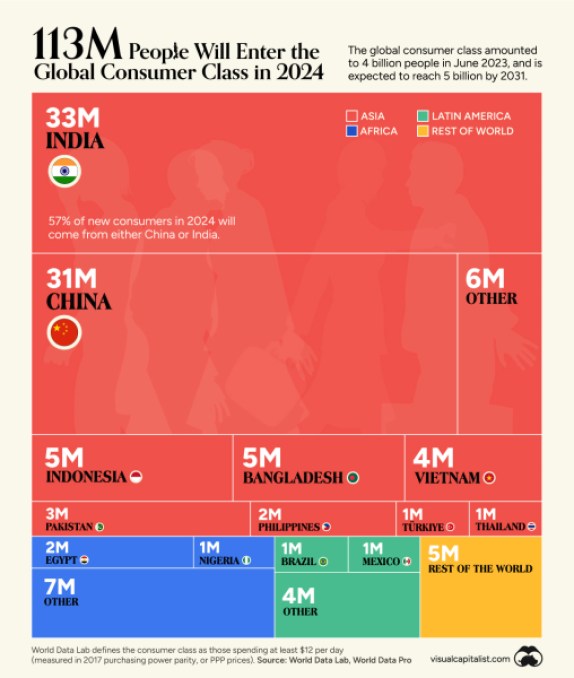

The Asian global middle class (people rich enough to travel, educate their kids and consume globally) continues to grow. In 2024 alone about 100 million additional Asian consumers will join this exclusive club. While the Chinese population is set to half by the end of the century, theoretically China could continue to grow its global middle class at the same time (currently about 200 million people strong).

International education and tourism will both be in high demand as long as Asian economies see growth.

As long as we rely on mining, agriculture, education and tourism we will be operating a high migration regime. I often hear people arguing that Japan managed to grow its economy while it aged rapidly and saw 30 years of population decline. Australia can’t follow Japan’s lead because our business models are fundamentally different.

Japan can grow its economy because Toyota, Mitsubishi, Honda, Sony, Nissan, Canon, and Fujitsu run factories across the globe utilising workers outside of Japan to produce their products.

Such high-tech manufacturing also lends itself to robotisation. Japanese banking, insurance, and IT businesses are scalable with relatively little input of labour. Japanese businesses don’t rely nearly as much on their local workforce as Australian businesses do.

Our Australian mining and agriculture businesses need people on the ground drilling and harvesting. These jobs can’t possibly be done outside of Australia. Obviously, these sectors will heavily invest into robots and AI to tackle the prolonged skills shortage. Mining only employs a quarter million of our 14 million workers in the first place.

Tourism also takes place exclusively in the country and necessitates a large local workforce. International education could theoretically be scalable through online programs and overseas campuses but at the moment all the money worth speaking of is created on Australian soil.

For the Australian business model to work we need local workers. A low migration scenario in Australia would necessitate a complete realignment of our national business model. I don’t think that is likely at all.

I would therefore argue that, looking 10 to 40 years (or even longer) into the future, the only plausible migration scenario for Australia is a high one. As always, I am happy to be proven wrong but continuing with our existing economic playbook is much more likely than a total overhaul of our economic system.

With high migration comes big challenges.

We need to grow our housing stock and infrastructure accordingly, we must integrate new migrants into our social fabric, and we must do all this in an environmentally sound way.

At least we know the challenges well in advance and can prepare to ensure we will be a prosperous nation in 2033.

Demographer Simon Kuestenmacher is a co-founder of The Demographics Group. His columns, media commentary and public speaking focus on current socio-demographic trends and how these impact Australia. His latest book aims to awaken the love of maps and data in young readers. Follow Simon on X (Twitter), Facebook, LinkedIn for daily data insights in short format.