The abdominal aorta is the largest artery in the body – roughly the width of a garden hose.

It supplies oxygenated blood from the heart to the abdominal organs and lower limbs.

Surprisingly, via research, it’s gaining traction as a reliable predictor of how poorly you might age.

When this heavy-duty blood vessel develops calcium deposits, we’re more likely to suffer a heart attack.

We might also develop late-onset dementia, and/or suffer falls and broken bones.

Can prediction translate to prevention?

With late-life dementia and cardiovascular disease increasing worldwide, scientists have been focusing on abdominal aortic calcification as a potential tool for identifying these issues in their early stages.

Abdominal aortic calcification (AAC) can be picked up in a bone density scan when it presents extensively.

But when there is just a sprinkling of calcium deposits – and scans of the artery are perhaps most useful for predicting and even preventing disease – the scans need specialist readers.

Edith Cowan University (ECU) in Perth – working with international teams – are among the leaders of this research.

They have developed an AI tool, using machine learning, that could make identifying AAC a simple matter of pressing a button.

Handgrip strength and falls

As we age, we lose muscle – and doing the simplest things, such as standing up and sitting down, become harder and then difficult without assistance.

This amounts to a loss of mobility and balance, and a greater risk of falls.

Studies have found that AAC is strongly associated with reduced handgrip strength, a measure of muscle loss. It’s also a measure of bone mineral density – and your potential for suffering a fracture.

A 2021 study from Edith Cowan found that AAC is linked with a 39 per cent higher risk of serious falls in older women.

By “serious falls”, the researchers meant falls with injuries that put you in hospital.

By the way, grip strength is regarded as a biomarker of your overall health. This includes overall strength, upper limb function, bone mineral density, fractures, falls, malnutrition, cognitive impairment, depression, sleep problems, diabetes, multi-morbidity and quality of life.

In May, ECU published a study that found losing muscle strength and slowing down our mobility could be evidence of late-life dementia.

The study examined more than 1000 women with an average age of 75. Those with the weakest grip strength “were found to be more than twice as likely to have a late-life dementia event than the strongest individuals”.

You can read more about that here.

What the researchers say

Josh Lewis is an associate professor of cardio-metabolic health in ECU’s Nutrition and Health Innovation Research Institute.

He is a co-author of several papers on abdominal aortic calcification and how it affects our health.

In an email, he told The New Daily:

“Healthy blood vessels are essential for the functioning of all of the organs in the body. We know as you age you get reduced blood supply to your muscles and bones resulting in poorer function, increased propensity to fall and fracture.

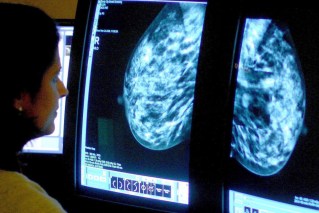

Calcification of the abdominal aorta, marked in blue, can predict how badly you might age.

“We have shown that abdominal aortic calcification is linked to poorer muscle function and decline as well as lower bone mineral density, as well as increased risk of falls and fracture.”

How can these associations be explained?

“We don’t know if it is because of AAC reducing the blood supply to the lower limbs, or because AAC is a marker of poorer blood vessel health in other sites such as the peripheral arteries, or because AAC is a marker of poor health overall.”

He said it was likely to be a combination of all of the above. The association between AAC and falls remains similar when adjusting for bone mineral density.

Heart attacks and stroke

In 2021, Associate Professor Lewis co-authored a paper that found people with AAC have a two to four times higher risk of a future cardiovascular event.

Further, the more extensive the calcium in the blood vessel wall, “the greater the risk of future cardiovascular events”.

People with AAC and chronic kidney disease were at even greater risk.

How is the damage done? Calcium deposits harden the arteries, block blood supply or can cause plaque rupture. This is a leading cause of heart attacks and strokes.

The factors contributing to artery calcification include poor diet, a sedentary lifestyle, smoking and genetics.

Associate Professor Lewis said at the time: “The abdominal aorta is one of the first sites where the build-up of calcium in the arteries can occur – even before the heart. If we pick this up early, we can intervene and implement lifestyle and medication changes to help stop the condition progressing.”

Late-life dementia

Abdominal aorta calcification doesn’t just damage the heart, it hurts the brain – and not just via strokes.

Associate Professor Josh Lewis. Photo: ECU

When ECU researchers examined 968 women from the late 1990s – and then followed their health status for more than 15 years – they found a link between AAC and late-life dementia.

The abdominal aorta doesn’t carry blood directly to the brain, but has a major role in regulating central blood pressure.

Aortic stiffness (including calcification) affects central blood pressure “which leads to damage to low-resistance organs, such as the kidneys and brain”.

The study, published last year, found that “one in two older women had medium to high levels of AAC, and these women were twice as likely to be hospitalised or die from a late-life dementia”.

This was independent of other cardiovascular factors or genetic factors.

Read more about that here.

New AI software for identifying AAC

AAC can be detected easily using lateral spine scans from bone density machines – routinely used to screen for osteoporosis. But finding AAC in these scans can require specialist readers and equipment.

As Associate Professor Lewis told TND: “Very extensive AAC is generally quite quick and easy to identify,” he said.

“However smaller areas of AAC can be challenging to identify and differentiate from imaging artefacts, such as overlying structures and bowel gas. You also need to assess these on specialised monitors in dark rooms.”

This can take between five and 15 minutes for each image.

To solve this issue, Dr Lewis and company turned to AI machine learning. More than 5000 images were used to train and test what’s known as a convolutional neural network algorithm.

This technology was first made famous in 2017. Thousands of images, taken from the internet, were used to train AI software to diagnose skin cancer. The algorithm reportedly did a better job than dermatologists.

A new ECU study developed software that is able to analyse about 60,000 images in a single day. The misdiagnosis rate was a mere 3 per cent – and the algorithms are a work in progress.

Associate Professor Lewis said: “Since these images and automated scores can be rapidly and easily acquired at the time of bone density testing, this may lead to new approaches in the future for early cardiovascular disease detection and disease monitoring during routine clinical practice.”