The Stats Guy: How the pandemic transformed Victoria’s population patterns

No other state was reshaped as Photo: TND

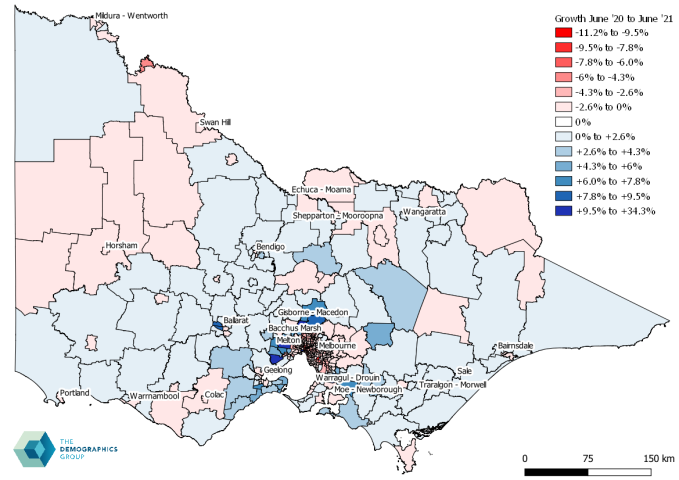

We finally have access to small area population estimates for June 2021. That means we can now see how 15 months of lockdowns – how remote work – reshuffled the Australian population.

Endless stories are hiding in this exciting dataset. Today we will explore how settlement patterns changed in Australia’s most locked-down state.

No other state was reshaped as strongly by the pandemic as Victoria.

Overall, the state lost population between June 2020 and June 2021 as (in net terms) 45,000 Victorian residents moved abroad or interstate. Current residents left locked-down Victoria, and potential residents decided against moving into a locked-down state. No surprises here.

Although Melbourne lost 63,000 people, the rest of the state gained 18,000. Pre-pandemic numbers looked very different. Between 2018 and 2019, 68 per cent of Victoria’s population growth took place in Melbourne.

Since the city was only home to 67 per cent of the state’s population, urban planners would speak of an intensifying centralisation of the population.

Victoria long wanted to decentralise, but these policies never eventuated. The economy just kept adding highly skilled knowledge jobs to the inner city and workers moved as close as possible to the Central Business District (CBD) to minimise the soul-destroying commute.

The clustering of office jobs required an army of service workers to look after hospitality, cleaning and maintenance. Everything in Melbourne evolved around the CBD – at least until the lockdowns hit.

Within Melbourne, the biggest losers were the job and education clusters around the CBD and Clayton (Monash University and adjacent precinct).

These markets were dominated by international students and skilled workers on temporary visas. Both groups were almost exclusively renters, which allowed for a quick exit once tertiary education moved online and temporary working visas ran out.

To better understand population movements, let’s grab a map and draw a few concentric circles around the CBD. The innermost area, within five kilometres of the CBD, lost 21,000 people between June 2020 and June 2021.

That translates to a massive loss of 5.1 per cent of the total residential population. The next ring segment, between five and 15 kilometres from the CBD, lost 36,000 people.

Since this area is densely populated, this “only” translates to a loss of 2.5 per cent of the total population. The 15-to-25-kilometre segment lost 25,000 people, or 2.1 per cent of all residents.

You see the pattern here. The closer to the CBD, the more markets are dominated by renters and temporary visa holders, and the more population loss occurred.

Once we reach the urban fringe – areas that are still technically within Melbourne, but further than 25 kilometres from the office towers of the CBD – the population increased significantly. A total of 18,000 net new residents moved to the urban fringe of Melbourne. That’s a strong growth figure of 1.3 per cent.

There are still plenty of boom regions within Melbourne, but this time the action isn’t in the CBD.

So why is there growth on the urban fringe? Basic demographics.

The largest population cohort in Australia, the Millennials, reached the family formation stage of the lifecycle just as the pandemic hit. Even without the pandemic, Millennials would not have left their one-to-two bedroom apartments in the inner suburbs behind.

Millennials will, bit by bit, be adding 1.7 kids to their households. That means Millennials are rapidly outgrowing their small inner-city apartments and need three- or four-bedrooms homes. The need for larger homes has only been turbocharged by the working from home (WFH) trend as knowledge workers demand a study in their houses.

Millennials’ family pressures

In the search for family-sized homes, Melbourne’s Millennials have left their Carlton, Fitzroy, or South Yarra apartments. They might well have stayed close to their current locations if affordable family-sized homes had been available.

Since Melbourne doesn’t have the family-friendly inner-city apartment market of European cities, Millennials essentially packed up their belongings, hit the road, and drove until they ran into affordable family-sized homes.

Millennials couldn’t buy into the middle suburbs because empty-nester Baby Boomers are still staying put. Boomers will only start selling at scale in the 2030s, when their health makes the family home a physical hazard.

The south-east, Cranbourne, and everything east of it did really well due to affordable house and land packages. In the west, Rockbank, Truganina, Tarneit and Werribee West boomed.

Areas with a high proportion of temporary visa holders (Hoppers Crossing, Werribee East) lost population. In the North, Mickleham grew by an astonishing 28 per cent in a single year, while Wollert added 18 per cent.

These suburbs made land available at scale at very competitive price points (by Melbourne standards). The major growth corridors face big problems in the years ahead as we risk allowing the population to grow at a faster rate than infrastructure. This problem isn’t easily fixed.

The private sector tends to provide housing at a faster rate than the public sector provides infrastructure. A solution to this could be to build infrastructure before the new population is allowed to settle on greenfield sites.

This is, of course, politically impossible in a city that grew by one Adelaide (1.3 million people) in the decade before the pandemic. Melbourne’s rapid population growth led to many bottlenecks (just ask the people of Point Cook as they attempt to leave their suburb via the one, traffic-chocked exit) that need to be fixed to allow for better traffic flow.

The voters of Point Cook would demolish any government proposing to add infrastructure for future populations rather than servicing long-ignored existing populations.

That’s the rough population pattern within Melbourne, but what happened in the rest of the state? What happened in regional Victoria?

All settlements outside of Melbourne combined added 18,000 people. The growth rate of 0.8 per cent might not sound impressive but in the context of a declining population in Victoria, that’s a major population shift.

Regional growth wasn’t distributed evenly though. Although towns within a commutable distance (let’s call this a two-hour drive) of Melbourne’s CBD boomed, towns outside of the gravitational pull of the state’s major job centre struggled.

Geelong and Warragul stand out as the main winners. Geelong especially will likely continue to be one of Australia’s most attractive growth regions. The commute to Melbourne is quick and will be even faster once rail upgrades are finished. The resurgence of manufacturing in Australia will benefit existing manufacturing hubs like Geelong.

As Millennials resettle, they seem to bet on the hybrid work model: work as much as possible from home, but be prepared to commute to the CBD a few times per week.

This rules out regional towns like Swan Hill, Shepparton, or Mildura as mass destinations for Millennials leaving Melbourne behind. Regional Victorian towns outside of a commutable distance to Melbourne need to become attractive destinations and job centres in their own right to attract population and soften the problems an ageing population brings.

These current settlement patterns will stay with Victoria for a while. There is still well over a decade worth of Millennials in the inner suburbs. They will continue to leave as they look for family-sized homes.

The next generation in the pipeline, Gen Z, is much smaller than the Millennials and, without a surge of migration from overseas, will be nowhere large enough to fill the apartments the Millennials left behind.

Also, now that the WFH genie is out of the bottle, Millennials will not go back to the office for five days ever again.

Once the Baby Boomers start downsizing (or dying) at scale in the 2030s, homes in the middle suburbs will flood the market and could potentially attract Millennials (then settled with teenage kids) back into Melbourne.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. We have urgent infrastructure upgrades to finish in the current urban fringe and regional growth corridors.