Bogong moth and ‘megabat’ grey-headed flying fox struggling to survive

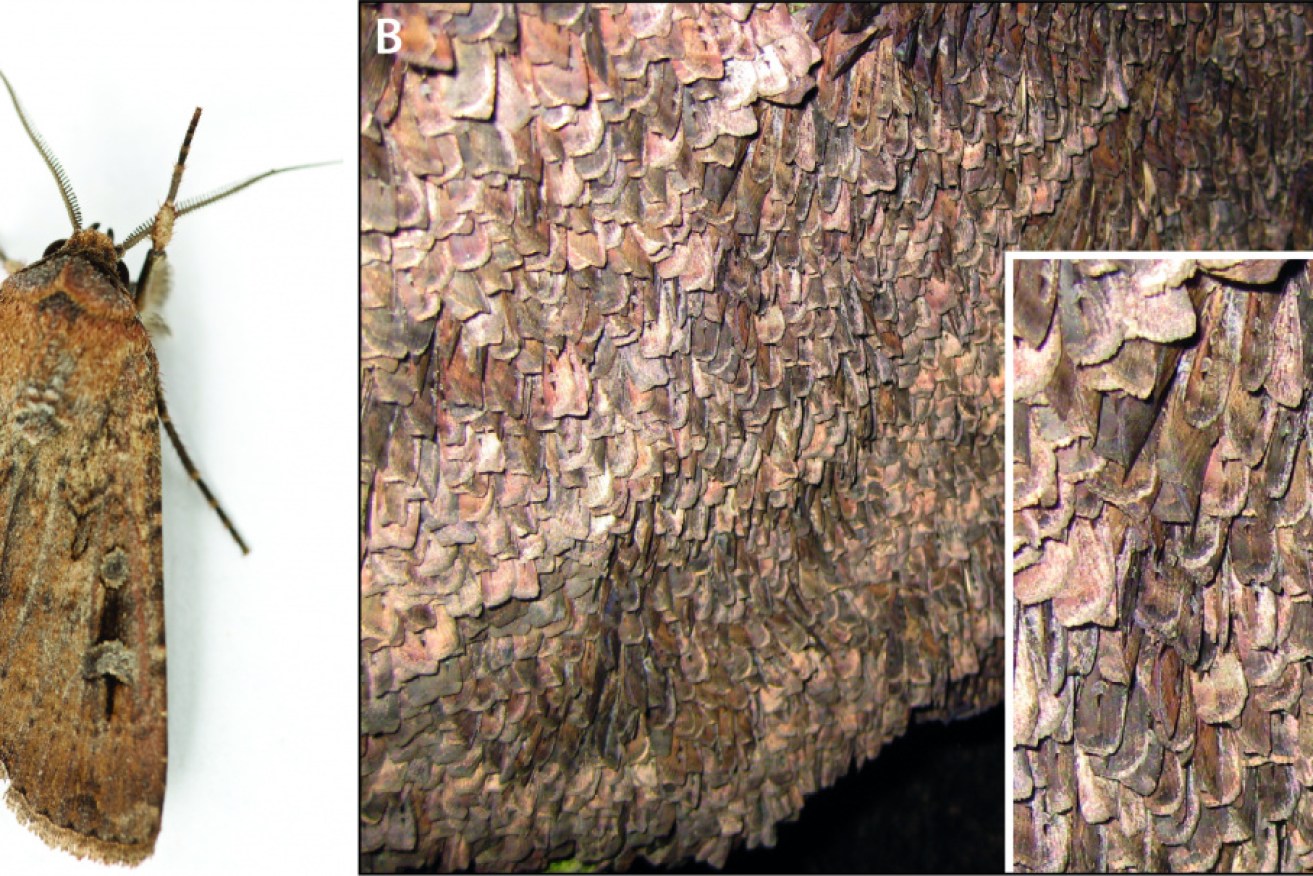

The bogong moth is on a 'red list' of endangered species. Photo: Monash University

Bogong moths once invaded Australian cities in their billions. Now they’re so scarce that the endangered mountain pygmy-possums that eat them have been found starving, their babies dead.

Until very recently, the moths were so plentiful that their epic spring migration from the plains of southern Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria to nice cool caves in the Australian Alps was an annual annoyance along the eastern seaboard.

In Canberra, dense swarms would routinely descend on Parliament House at night when its bright lights were shining.

But in 2017 and 2018 the moths largely failed to arrive and on Thursday, the species was formally listed as endangered on a global red list of threatened species compiled by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

The IUCN Red List has just been updated, with the number of known animals, fungi and plants at risk of #extinction exceeding 40,000 for the first time: https://t.co/FvJhUWw1rm pic.twitter.com/I0sH90ByL6

— IUCN Red List (@IUCNRedList) December 9, 2021

The mountain pygmy possum – Australia’s only hibernating marsupial – has been on the same list since 2008 and it’s in the critically endangered category, one notch below extinct in the wild.

There are thought to be fewer than 2000 left in three populations in the alpine and subalpine rocks and boulders of the Bogong High Plains, Victoria’s Mount Buller and Mount Kosciuszko in NSW.

Threats to the possum include climate change, loss of habitat and predators like feral cats and foxes.

Some conservationists fear the loss of their springtime food source, crucial for them to refuel and rear healthy young, could be enough to seal the possum’s fate.

After the moths stopped coming in 2017 and 2018, many female pygmy possums were found underweight and unable to produce enough milk. In some cases that resulted in the loss of entire litters.

A bit of guidance for when you're using #MothTracker athttps://t.co/JTv7lkl6YO. #AgrotisInfusa #BogongMoth https://t.co/IMfhIwCeOp

— Peter Caley (@PeterCaley1) December 1, 2021

The Australian Conservation Foundation says the fact that the bogong moth and the possum now sit side by side on the IUCN red list is a sobering example of the world’s extinction crisis, and how the loss of one species frequently causes or contributes to the loss of another.

ACF nature campaigner Jess Abrahams says the moth’s population collapse a few years ago was staggering, with scientists believing a mix of extreme droughts, pesticides and changes in agricultural practices were to blame.

Caves that once heaved with tens of millions of moths were empty when scientists went to inspect them.

There was some evidence of a modest population recovery last year, but experts say numbers remain very low.

As awful as the impacts have been for the mountain pygmy possum, Mr Abrahams says they are at least on the radar. But he worries about the other effects that are yet to reveal themselves.

“There’s birds, and reptiles and other marsupials in the mountains that also rely on the bogong moth,” he says.

“In food chains you have these flows of energy and the bogong migration was a massive flow of high nutrients up into the mountains that helps these animals that have survived a harsh winter be fully fed for spring and summer.

“We can see the the first few cascade effects, like starving pygmy possums, but who knows where these flow on effects end.”

“Their supermarket has been destroyed…and there isn’t another one within flying distance”. The Grey-Headed Flying Fox is being threatened with extinction by the effects of climate change, their future looks grim.

📸 #AnnetteRuzickaPhotography pic.twitter.com/zDGac9XrQJ— Australian Conservation Foundation (@AusConservation) July 5, 2020

Another of the Australian species added to the IUCN red list this year is Australia’s largest bat – the grey-headed flying fox, which has a wingspan of over one metre.

The megabat – also among the world’s largest – has been in trouble for a while.

It’s found in Queensland, NSW and Victoria and is listed as vulnerable nationally thanks to its habitat being cleared, and culling by farmers before the species was protected.

Mr Abrahams says Australia cannot afford to lose the vast number of plants and animals that are already in deep strife, with the full effects of locked-in climate change yet to play out.

A UN-backed report, released two years ago, warned the window to save the planet’s biodiversity was closing, with one million species at risk of extinction.

“Australia has a terrible record on species extinctions,” he says.

“We are blessed with some of the most incredible places, beaches, animals, and plants on the planet. But we are losing them before our very eyes, and this red list is evidence of that.”

He said urgent action was needed to turn around the extinction crisis and that demanded strong federal leadership on climate change, better national environment laws, and crucially the money that’s required to nurse species back from the brink.

-AAP