Critics of the federal government’s botched Robodebt system fear Centrelink’s new debt collectors have failed to learn the mistakes of the unlawful recovery program.

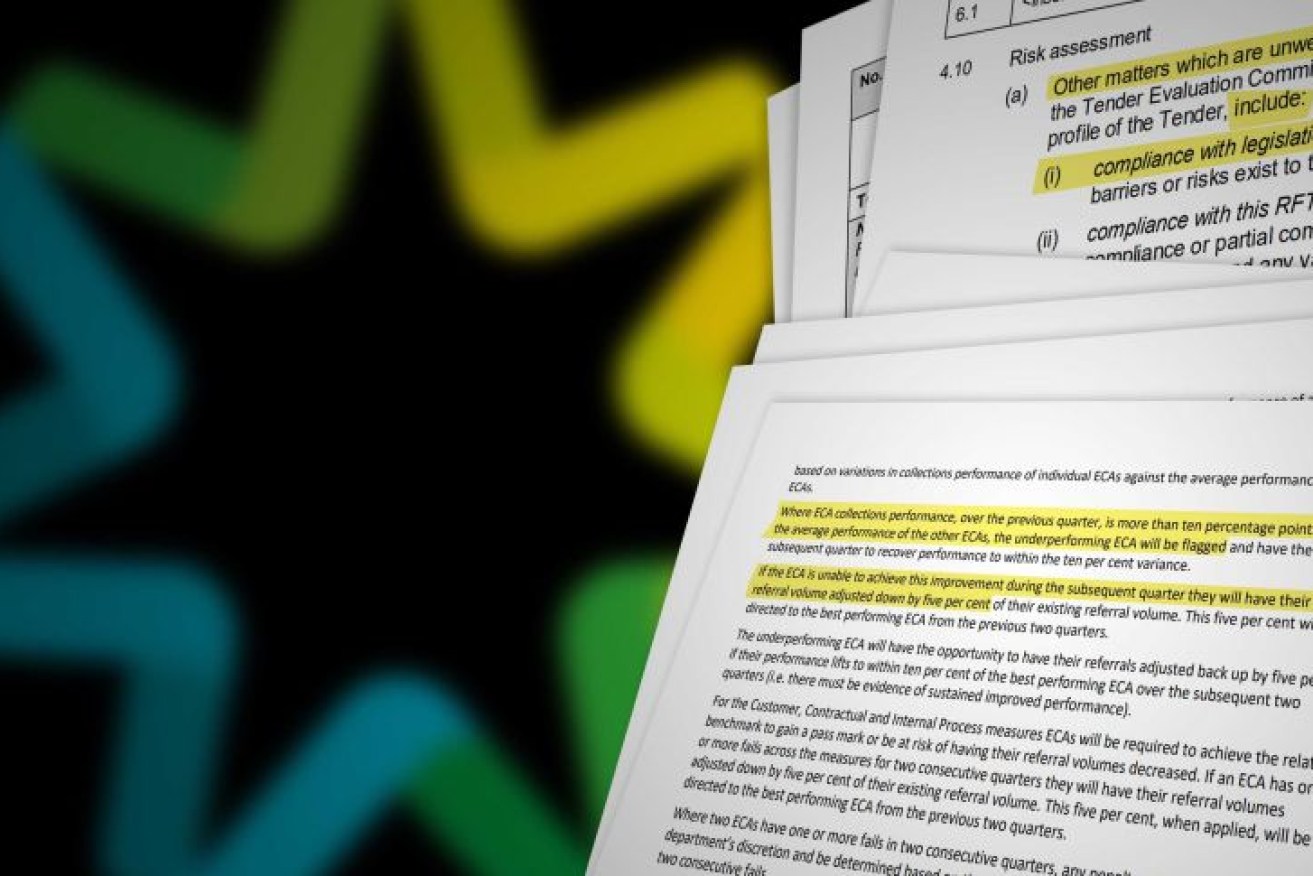

Tender documents reveal a panel of new collection agencies must continuously compete to beat rigorous financial targets for recovering money from customers: Either winning more work or facing penalties.

Australian Unemployed Workers Union spokeswoman Kristin O’Connell said she was surprised the department was going to outsource the work.

“As the government’s own documents acknowledge, this outsourcing model means debt collectors have incentives that can result in ‘unintended and perverse’ behaviour to meet targets and trigger fees,” Ms O’Connell said.

Australian UWU spokeswoman Kristin O’Connell says privatising debt collection exposes people to companies who are not accountable. Photo: ABC News/Adam Wyatt

Tender documents for the new contracts reveal Centrelink will engage three different debt collection agencies.

Agencies that collect fewer debts will receive less work.

Initially the work will be split in thirds, but those that collect a greater percentage of debts will be given an increased share of the work.

Those that fail to meet targets will be penalised by losing work.

The three contracted agencies will be benchmarked against each other.

Elise Klein is a senior lecturer in public policy at Australian National University, who has done extensive research on Robodebt and other government collection programs.

“There’s an almost encouragement that you’re seeing there around performance and going after people,” Dr Klein said.

“When there are performance measures, people cut corners and that can encourage unscrupulous behaviour … because they’re trying to maintain a level of performance.”

Senior ANU lecturer Elise Klein is concerned rival debt collection companies will have to compete with each other to win more work and avoid financial penalties. Photo: ABC News/Rudy De Santis

Robodebt lessons

The Commonwealth is in the middle of a $1.2 billion settlement over Robodebt.

The failed system was widely criticised for using computer algorithms to raise debts against hundreds of thousands of welfare recipients, with little to no human oversight.

Carissa Smith was chased for a fake $11,000 debt, allegedly accrued years earlier.

“I feel for the people that didn’t make it, because I know how close … I was, you know?” she said.

“They just don’t realise what they do to people, that’s all. They have no idea.”

Ms Smith was pursued by the agency for years, despite having payslips that proved she didn’t owe anything.

She is concerned the new contracts will make it impossible for companies, which are required to hit targets, to listen to customers.

“There’s going to be so many innocent people, you have to constantly prove yourself,” she said.

“You’ll never be able to fight against them.”

Whether or not new external debt collectors break the law won’t be weighed as a factor in winning the contracts.

While tenderers must comply with legislation, such as the criminal code and racial, sex, age and disability discrimination laws, there don’t appear to be penalties if they do not.

The tender documents suggest that debt collection agencies can break the law and still win a contract.

Ms O’Connell said she was worried what could happen.

“It’s disturbing that after the Robodebt fiasco, which drove people to suicide and unlawfully took money from hundreds of thousands of people, the department would consider outsourcing with requirements so lax that they don’t even require debt collection activities to be lawful,” she said.

‘I do not accept that people have died’

Critics of the scheme argue it has contributed to self-harm and deaths by suicide.

Four hundred and twenty-nine people aged under 35 died after receiving a Centrelink debt notice (Robodebt notice) from July 2016 to October 2018, according to data released by the Department of Human Services.

This compares to 3,139 deaths of people aged between 15 and 35 in 2016 overall, according to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

The department does not collect data on the cause for death in these cases, but nearly a third – 663 people – were classified as “vulnerable”, which means they had complex needs like mental illness, drug use or were victims of domestic violence.

A spokesperson for then-human services minister Michael Keenan told triple j “any suggestion that the Department of Human Services’ debt recovery efforts have contributed to customer deaths is simply not supported by the facts or statistics.”

In a Senate hearing in July, the head of the Department of Social Services, Kathryn Campbell, strongly denied that people have died by suicide as a result of the scheme.

“I do not accept that people have died over Robodebt,” she said.

Ms Campbell said suicide and mental health were difficult subjects, but that she rejected that Robodebt has caused people to die by suicide.

The agencies selected to collect debts are not required to be members of the Australian Financial Complaints Association, making it difficult for customers to complain about their treatment or have an independent voice adjudicate disputes.

“From this tender document, I can’t see – in the space of debt collection – what really has been learned from Robodebt,” Dr Klein added.

“When there’s an emphasis on competition (such as incentives and targets), taking account of people’s circumstances comes second or third down the list.”

Complaints considered ‘threats’

The debt collection agencies that win contracts must have a plan to deal with the “management of escalations and threats” from customers.

The key ones are threats of violence or self-harm “as well as events that have potential for serious adverse impact to the department’s reputation”.

Specifically, companies must also have an action plan for when customers threaten to contact members of parliament or the media and inform the department “within 1 hour” of such a threat.

That clause speaks to a larger issue, according to Dr Klein: That people needing the support from welfare payments aren’t trusted with them.

“Social Security set up a ‘system of distrust’,” she said.

“In the tax system you’re trusted. So you report your income and generally you’re trusted. You may be audited.

“But with social security people are under so much scrutiny … it operates on a system of distrust and this whole piece of debt collection speaks to that.”

Debt reduction target

Centrelink does most of its debt collection itself.

The contracts are for external debt collectors, who made up 6 per cent ($105 million) of the total debt ($1.75 billion) the agency clawed back from customers.

“Reduction in the size of the existing debt book is a priority,” the documents state.

“The agency has an obligation to make attempts to recover debt owed to the Commonwealth by its customers.”

The contracts will run for three years, with an option to extend for up to two more years.

Services Australia, the agency in charge of Medicare, Centrelink and child support, declined to be interviewed but in a statement, general manager Hank Jongen said the agency was legally obliged to recover social welfare debts.

“The use of external collection agents is not new, and has been part of Services Australia’s process for recovering taxpayer money since the mid-1990s,” he said.

“The current request for tender process simply ensures we will continue to have a panel of (external debt collectors) in place to deliver these services when the current panel arrangement ends.”