‘Peak stupidity’: Calls to diversify Australian exports criticised

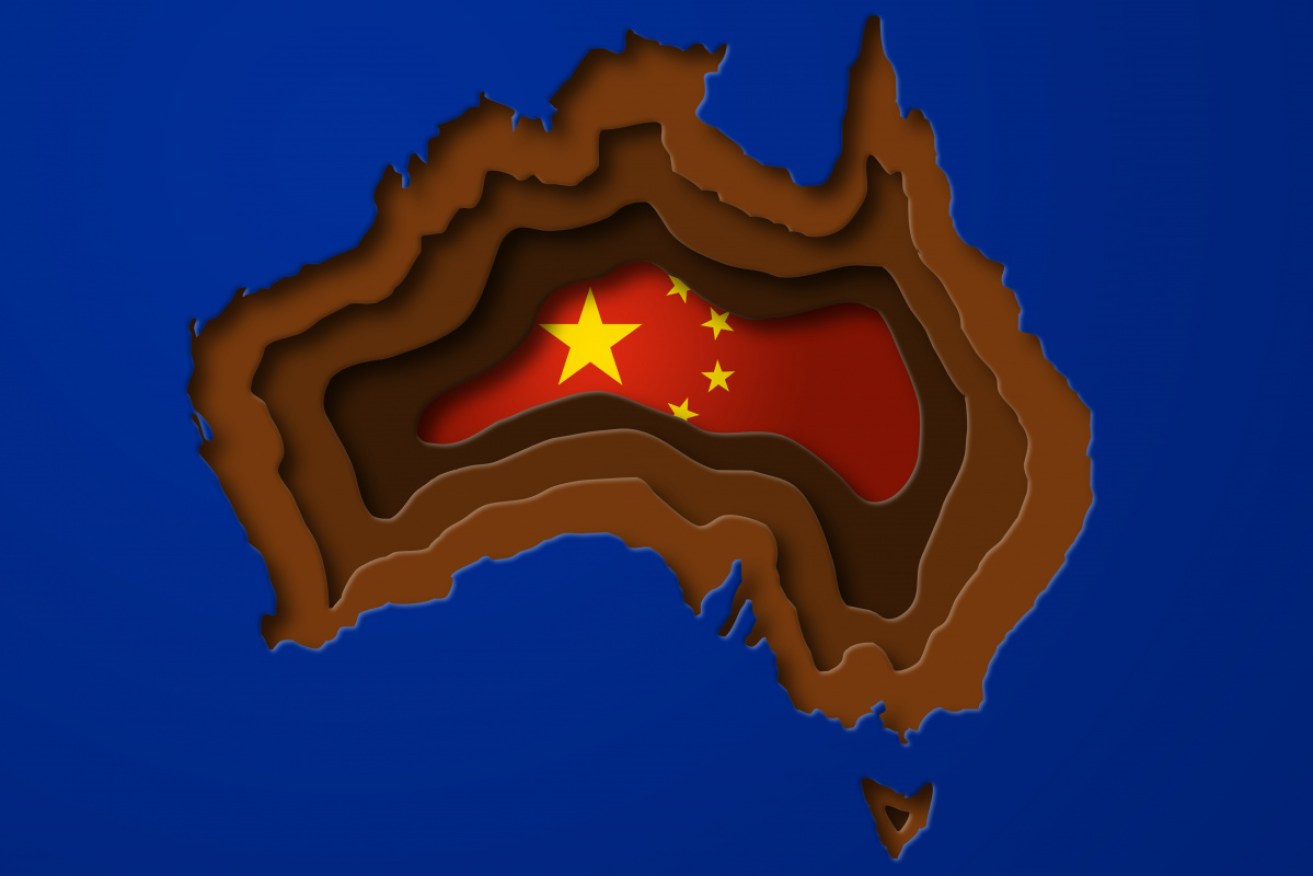

Australia has a complicated relationship with China, but may have to make a stand. Photo: Getty

Calls to diversify Australian exports following a diplomatic blowup with China represent “peak stupidity,” according to one prominent economist.

Market Economics director Stephen Koukoulas said pressing Australian businesses to diversify their exports was naive as they can only sell to countries that “want to buy the stuff we make”.

“If countries other than China do not want to buy our iron ore, have holidays here, buy our barley, we cannot make them,” Mr Koukoulas said on Twitter.

“If China does, terrific! We sell heaps of those and other things to China and benefit hugely from it.”

Mr Koukoulas told The New Daily it was “an observable fact” there is an economic issue with our “heavy trade dependence on China”.

“But to say we’ve got to change it, I just don’t understand it,” Mr Koukoulas said.

“If an Indonesian business said, ‘Look, we want to buy more of your coal’, I’m sure the [Australian] coal producers would deliver.”

Instead, Mr Koukoulas believes Australia will boost its exports to China over the next 12 months, as China’s economy will recover faster from the pandemic than Japan, the United States and Europe.

Tweet from @TheKouk

His comments come after Trade Minister Simon Birmingham told the ABC’s Insiders that his Chinese counterpart was ignoring his calls amid an escalating trade dispute over beef and barley.

China has accused Australia of using subsidies to help its farmers sell barley in China at below-market prices – a practice known as “dumping” – and threatened to impose an 80 per cent import tariff on the grain as a result.

It has also banned imports from four abattoirs for allegedly failing to meet Chinese health standards – an “informal retaliation” that provides the Chinese government with plausible deniability against “accusations of explicit economic bullying,” according to academics from the Australian National University.

Although the proposed tariff on our barley exports is linked to an 18-month-old dispute, China’s actions came after Australia called for an independent inquiry into the origins of the coronavirus – prompting calls for more economic diversification.

As it stands, almost a third (32.6 per cent) of Australian exports go to China.

According to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, in the financial year 2018-2019, most of that arrived in the form of iron ore ($63.1 billion), coal ($14.1 billion) and natural gas ($16.6 billion).

As for barley, at least half of the nation’s exports typically end up in the Middle Kingdom, as part of an annual trade that was worth $1.5 billion in 2018 and $915.4 million in drought-affected 2019.

Calls for diversification are misguided

University of New South Wales economics professor Richard Holden said Australia’s large export dependence on China left it vulnerable to changes in the global superpower’s economic policies and market conditions.

But he said the federal government should protect the Australian economy from these adjustments using fiscal and monetary policy, rather than pressuring businesses to diversify their exports.

Among other things, this means making sure Australia “has the right mix of skills” to adapt to changes in the economies of our major trading partners.

“Stuff is sold where we can sell it,” Dr Holden told The New Daily.

So I don’t think calls for diversification are particularly well founded.”

Meanwhile, UTS Australia-China Relations Institute director James Laurenceson and project and research officer Michael Zhou argue in a recent blog post: “A significant trade exposure to China is not, in itself, compelling evidence that Australian businesses have been irresponsible in their risk management, nor that the country as a whole is ‘too dependent’.”

Tweet from @InsidersABC

No substitute for China’s economic might

“In terms of exports, Australian businesses selling heavily into the Chinese market stand to lose the most if that market is disrupted,” the researchers write.

“This provides a strong incentive to be well informed about both opportunities and risks, and take steps to mitigate the latter,

“This is not to say that business risk management is failsafe. Rather, simply that the basic incentives businesses have to get the risk/return equation right are, for the most part, not there to the same extent for the Australian government.”

The academics say “there are important qualifications, however”.

Firstly, businesses heavily exposed to China cannot expect a federal government bailout should the Chinese economy suffer a downturn.

Secondly, they must price into their business models the risk of harmful policy changes from the Chinese government, as the Australian government will sometimes take decisions judged to be in the national interest that run counter to Beijing’s interests and provoke retaliation.

But these qualifications do not imply that it serves the national interest for the Australian government to force a decoupling of the two economies,” the academics argue.

This is mainly because no economy is large enough to match our trade with China.

“At a national level, claims of being ‘too dependent’ on China for exports assume that an alternative country stands ready to buy Australian goods and services. That is, Australia can be ‘less dependent’ on China by being ‘more dependent’ on, for example, India or Indonesia,” the academics said.

“But the fact is that of the net $180 billion increase in Australia’s annual export value over the past decade, just one country has been responsible for delivering 60 per cent of the jump: China.”