The 1970s movies that predicted a modern crisis before anyone else saw it coming

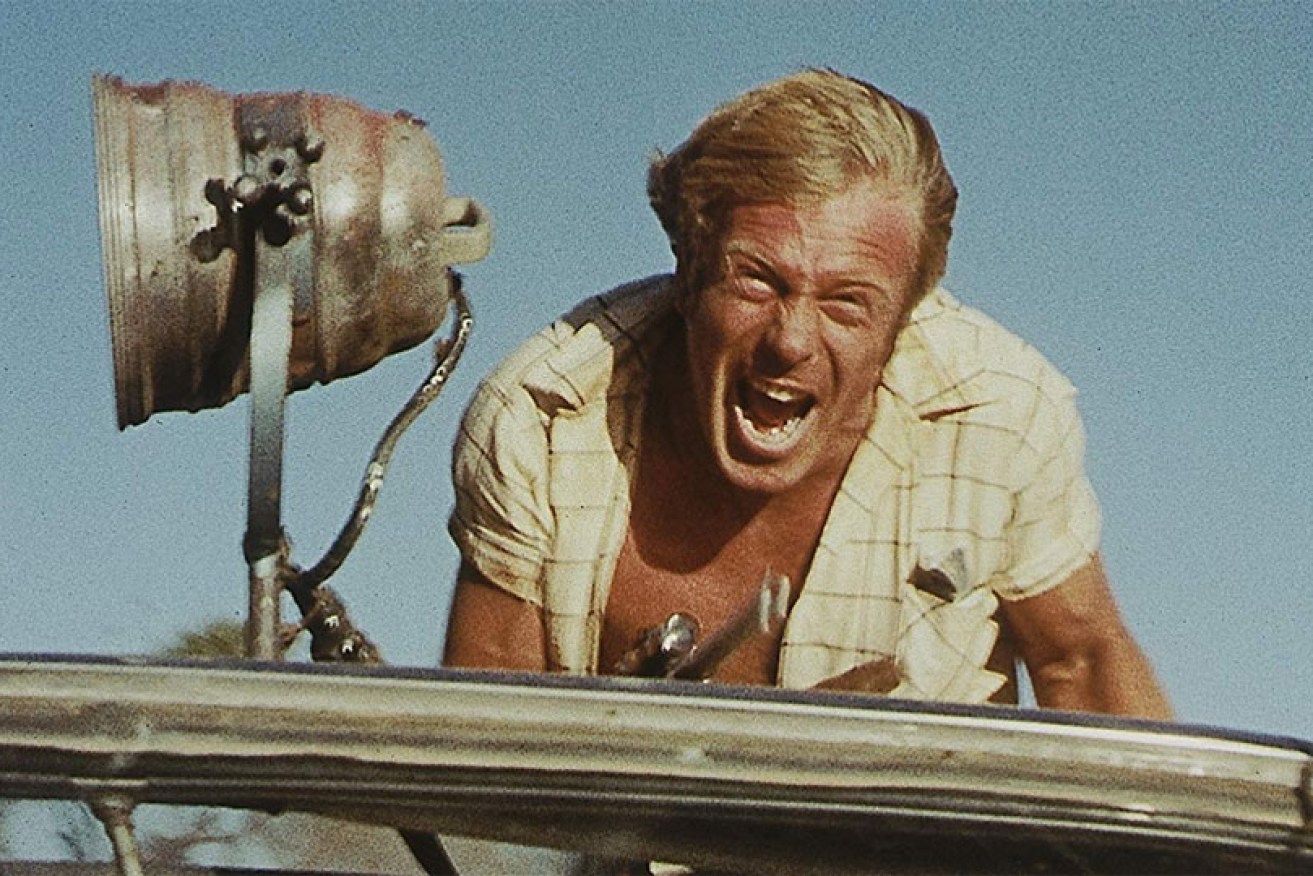

Jack Thompson in Wake in Fright, which Martin Scorsese said left him "speechless." Photo: Drafthouse Films

1970s Australian movies were awash with ripper blokes, topless women, young wannabes who became enduring stars, dusty pubs with wide verandas and narrow minded patrons.

And, it turns out, plots that have predicted the modern environmental situation.

Unlike the sentimental use of the Australian landscape in films before and after, in the 1970s the natural environment wasn’t just a backdrop, it often played the villain, or at least the antagonist.

The climate crisis demonstrations and closure of Uluru to climbers reminded Australians that environmental degradation is going to be the defining point of political debate in coming decades.

There’s nothing like a global existential crisis to make people sit up and pay attention.

Many are now asking why we weren’t paying attention before the situation reached China Syndrome levels.

Truth is we were, but both the strength and weakness of early warning systems is the fact that they are early, and can therefore be ignored.

Australian ‘New Wave’ cinema, the cinematic renaissance that flowered mostly through the curatorship of the Gorton and Whitlam governments in the 1970s, saw an unprecedented level of feature film production in this country.

Land, and Australian’s relationship to it, was a theme oft explored in New Wave cinema.

This began in 1971 with Wake in Fright, an Australian/US coproduction that Nick Cave once described as “the best and most terrifying film about Australia in existence.”

It is terrifying, relating the story of a sensitive school teacher who suffers a moral crisis while marooned in an outback town and exposed to the brutality of the locals.

Wake in Fright’s central thesis seems to be white Australians were unified by a hatred and fear of their natural environment, and attacked it accordingly.

This was demonstrated in particularly gruesome fashion through an extended night-time kangaroo shooting scene that showed the extent to which Australians were prepared to destroy their environment in order to control it.

Peter Weir’s iconic Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) told a different kind of environmental story.

Supposedly based on real events (since debunked) surrounding the disappearance of a group of schoolgirls at the eponymous monolith on Valentine’s Day In 1900, Picnic once more shows Europeans imposing themselves unnaturally on an ancient landscape, which this time strikes back.

The same theme was explored in 1978’s The Long Weekend where an unhappy suburban couple camping at a remote beach disrespects the environment, including killing a dugong.

They discover to their cost that nature will only take so much abuse before it attacks.

Weir went a step further than Picnic in 1977 with his next film.

Picnic proposed that the natural environment has dangerous secrets, which can hurt us.

The Last Wave, however, warned that we have ignored the signs and a cataclysm is coming.

The film opens with groups of Australians hit by bizarre destructive weather events – something that the country increasingly accepts as standard operating procedure.

Then a Sydney lawyer defending a group of Aboriginal men charged with murder suspects the killing and premonitions he is experiencing are linked to an apocalyptic Dreamtime narrative.

In the last scene he emerges onto Sydney’s Avalon beach to gaze in horror as a tsunami engulfs the city.

The movement wound down not long after the release of Mad Max 2 (1981), which depicted society fragmenting and descending into violent conflict after an over-reliance on fossil fuel triggers an apocalypse.

And the only person who can lead the survivors out of darkness is Mel Gibson.

I pray I go in the first wave.