Bush School: The teacher who made the grade in a tiny country town

Peter O'Brien taught at a bush school is outback New South Wales in the early 1960s. Photo: Sean O'Brien

It’s not often you get the chance to see what happened to a set of kids after the passage of 60 years or to find how their tiny, remote village had weathered a lifetime of change.

Bush School was my recently published memoir of two years spent as teacher-in-charge at a one-teacher school in the remote, northern New South Wales, New England village of Weabonga.

Set in the early 1960s, I’d introduced 18 children, aged between five years and 15. Sixty years had passed, though, and those youngsters were all senior citizens now. What had become of them?

I hadn’t been back to Weabonga for nearly 60 years. At 20, when I first went as a teacher, I’d been quite challenged by both the village and the tasks at the tiny school. The children in 1960 and 1961 were simply delightful, though; they had made my teacher-in-charge duties seem like shared fun and happiness.

Some of the ex-students had made contact following the book’s publication and the idea of a reunion after 60 years was attractive to us all.

Some of the ex-students had made contact following the book’s publication and the idea of a reunion after 60 years was attractive to us all.

When we met in November, at a short-stay cottage hired for the occasion in

Weabonga village itself, nine of the original students from 1960 arrived. Their presence provoked an emotional response. Sean, my son who accompanied me on the trip, lined up the nine of them for a photo with me standing in front. A sentimental vibration ran through me: avoiding a few tears was not easy.

An obvious excitement had arrived with the ex-students. Their happiness shone out and every person was swept up by the cheer, goodwill, contentment and enthusiasm. As kids they’d been delightful. As adults they remained the same. Their pleasure in the book, which had brought us all back together, was obvious.

That the little village and school had been written up and given a permanency clearly met with acceptance and approval.

Chatting was easy. One set of brothers from an original village family came, they wanted to talk with me about their mum, Betty – who I’d called Jill in the memoir.

After their Dad had died, the three boys replaced the old, falling-down, rudimentary house, where I had lived with them for three months in 1960, with a comfortable, snug abode. Betty’s constant pain from chilblains ceased as soon as she moved.

Past students of Peter O’Brien came together once more. Photo: Supplied

She had forbidden the new cottage build, claiming it was more important to her that her boys invested their money in their grazing-property and its flocks. But her sons insisted. A small memorial card, hand-written with a beautiful photo of Betty, snapped with the gentle half smile I remembered as typical of her in 1961, was slipped to me.

A further set of brothers and their younger sister recalled to me our only excursion from the little school, to take part in the folk-dance competition of the Small Schools’ Section of the Tamworth Annual Eisteddfod.

The children had sung the tunes to accompany their dance and the family remembered how we all sang or hummed Skip to my Lou. Recalling that, between the dancing and singing, the kids were all out of breath by the end, raised a smile for all of us.

The school as it stands today. Photo: Supplied

Lots of stories and yarns about the school days were spun and enjoyed.

One tale provoked much laughter. Two of the ‘village boys’ told how they’d decided one late afternoon to raid the strawberry patch near the school gate. They were sure I’d left for the day but, suddenly, I appeared on the veranda, demanding to know who was there and what was going on.

One thought he was well hidden, but the other offered up both boys’ names. Unable to hold back their laughter 60 years later, the ‘dobber’ was thanked for his fearless honesty.

When Billy – who in the book was called Mark – came to join the group another tale developed: the day Billy blew up the drop-pit latrine. The toilet was emitting a terrible stench, but Billy claimed he knew what to do.

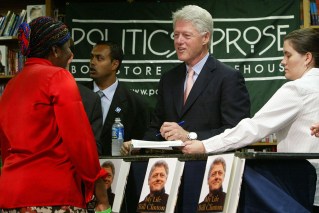

Peter O’Brien, second from right, before heading bush, 1956. Photo: Supplied

Given the go-ahead, he filled a small can with petrol and poured it into the pit then threw in a lit newspaper. Billy was delighted that the toilet exploded with a massive noise and a bit of a shudder all round, but the problem was solved.

I had to ask what happened to the pit’s contents as I had a disturbing vision of material flying in all directions, but Billy proudly claimed all that stuff just vanished. The temperature and power of the explosion evaporated all the matter and dispersed it entirely.

Sharing a laugh, we acknowledged that Billy had struck again. An inquisitive and creative youngster, he’d often lightened the atmosphere in our shared days at the little school, and it was pleasing he could continue to do so years later.

Only one story that afternoon related to a teaching moment and it pleased us all to hear it. Gary – who’d been called Rick in the story – recalled how he was at the blackboard with me one morning in 1960.

He was creating a story about rabbiting with his dad and I was helping him write it up in chalk.

Peter revisiting the village of Weabonga. Photo: Sean O’Brien

He wanted a sentence added about what happened when a rabbit sprang out of a burrow. I was ready with the chalk, when he dictated, “Dad said we’ll have to catch that bugger.” It seems my hand shot out as quick as lighting, landing lightly across the lad’s mouth and I suggested we’d leave the story right there for the day.

We heard only happy or amusing stories so, putting them all together, it seemed we had got many things right when we were all together in the ‘Bush School’. Our 60-year reunion had been a stunning success. The day had been extraordinary for us all.

In the evening, Sean and I wound down from the perfect day by sharing a cold drink on the deck.

During the reunion we’d heard visitors were arriving in the village nowadays in increasing numbers.

The little school, which had been heritage listed and preserved much as it had been in 1961, now provided a cosy home for Bert. Often he met strangers peering and poking around. He might gift them a guided tour inside.

Billy, who’d retired to live in the original family home in the village, had spoken of finding groups of visitors who delighted in hearing his stories of the past.

Weabonga is a bit of a trek from, well, anywhere. Photo: Sean O’Brien

They were fascinated to learn about the gold rush times and the mines – The Highland Mary, The Darned Hoodlum, The Rainbow, The Tichbourne, The Storm Queen – while the historic remains, scattered around the village, fascinated them.

Gary’s guided tours of the old police station, which he’d made his home, always met with myriad questions and loads of thanks.

It seemed possible that, with deliberate attention to signposted walking trails and interpretive plaques, new sources of tourist income could open up — if the villagers wanted.

Weabonga stands in a beautiful little valley, nestled in the hills of the Great Divide, the climate is benign most of the year, the air fresh and crisp and all is quiet apart from the bird life, which is abundant. A better place to wind down and recuperate would be hard to imagine.

Weabonga had lost much in the 60 years since I’d taught there. Gone were the school, the post office, the community hall, the little churches and the tennis club. More dramatically, all the children had gone.

The endearing village of Weabonga. Photo: Sean O’Brien

A 1960 village population of up to 30 was now reduced to about seven. Though barely a village remained, what was not lost was the natural attraction and the pleasing climate. Because it was small, remote and beautiful, might Weabonga begin to attract a new population and the village find itself on the rise again in our strange new, post-COVID world?

At the end of the day I said to Sean, “If the only thing I had achieved in life had been to give the Weabonga children two good, happy, productive years of schooling then I feel I would have lived a worthwhile existence.”

Sean reassured me I’d achieved considerably more than that but agreed that such an outcome was worthwhile of itself.

He’d fallen in thrall to Weabonga as well.

Bush School by Peter O’Brien, RRP: $29.99, Allen & Unwin, is available now.