The creepy case of the Beaumont children and ‘The Satin Man’

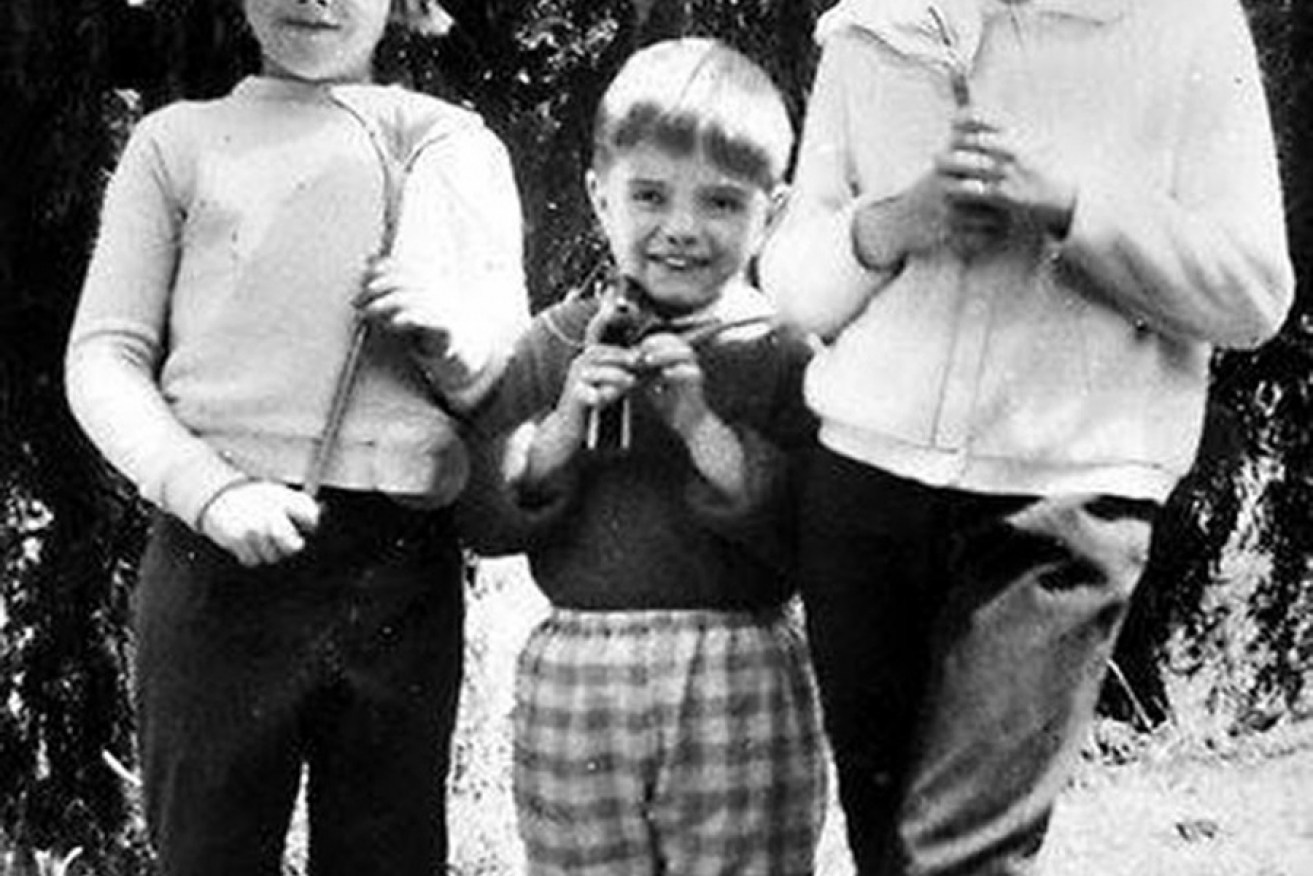

The case of the Beaumont children (from left) Arnna, Grant and Jane, remains unsolved over five decades later. Photo: AAP

The following is an excerpt from The Satin Man, a book published in 2013 about the disappearance of the Beaumont children – Jane, 9, Arnna, 7, and Grant, 4 – from an Adelaide beach on January 26, 1966.

The book refers to Hank Harrison, a local factory owner with a fetish for satin, who later turned out to be suspect and “confirmed paedophile” Harry Phipps (Phipps died in 2004).

His estranged son told police he saw the Beaumont children in the backyard of his home the day they vanished.

Mr Phipps’ North Plympton factory was excavated in 2013 after the book’s publication but police found nothing.

However, this week a Seven News investigation found detectives from the Major Crime Investigation branch were conducting a new excavation of the property, thereby reopening the cold case.

For legal and privacy reasons, the authors of this book changed the names of the people being investigated. Harry Phipps was referred to as Hank Harrison.

Hank Harrison: Aka ‘The Satin Man’, a wealthy businessman known by friends and family for sexual deviancy.

Warwick Harrison: Hank Harrison’s estranged son, who had always believed his father had something to do with the children’s disappearance.

Stuart Mullins: Co-author of The Satin Man.

Rose Parker: The first wife of Warwick’s close friend Steve Parker.

Rose said she’d seen evidence of Hank’s ‘satin fetish’ and that he was a ‘sexual deviant’. She supported Amanda and said his fetish ‘was very well known in close family circles’.

You could not wear satin clothes to the house, Rose said, and there was a very strict ‘code’, because Hank was easily sexually aroused and he ‘could not help himself’ when he came into contact with satin.

“I knew what was going on underneath those satin garments he wore,” she said, “and I stopped my children from coming to the house”.

She also confirmed that there was a room in the adjoining house you were not allowed to go into. “Hank had two sides to his personality … one was his public face, which could be very charming, and the other side was a very nasty, vindictive man.”

Stuart found his best rapport with Rose’s former husband, Steve Parker. Steve was close to the family and had known Warwick when he was a teenager.

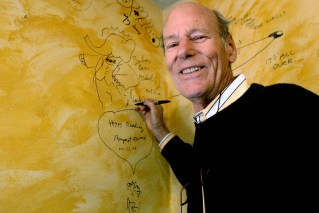

Harry Phipps, who in the book is referred to as Hank Harrison.

Stuart formed a friendship with Steve over the seven years that followed; they met regularly in Adelaide for long discussions about everything from business (both Steve and Stuart run their own businesses) to spirituality and mental health issues.

Steve helped Stuart with names and addresses, and provided him with context for some of the information Stuart discovered about the Harrison family.

“Steve was not surprised at all that Warwick may have been sexually abused,” Stuart says. “He had heard rumours for many years. Steve definitely knew about Hank’s satin fetish; that satin ‘turned him on’ greatly, and that he also wore dresses.”

He knew that Hank was initially raised as a girl – these were well known stories in the inner family circle – and about the private room Hank kept in the house next door. “By all accounts, nobody was allowed anywhere near that room,” said Steve.

Steve’s father worked for the government; the family travelled a lot and lived overseas. Steve could remember his father going to Hank’s home one night in the late 1960s, and drunkenly yelling out, “I know what you did, you bastard.”

Steve also said that on many occasions during the 1960s, either while walking home from school or heading up to the shops at Glenelg, he would see Hank driving around Glenelg in his Pontiac. “He wasn’t dictated to by [office] hours,” Steve said, which might explain why Hank could have been home on Australia Day 1966, a normal working day. “He seemed to spend a lot of time cruising around town.”

Warwick learnt to drive in an old truck at the factory, Steve remembered, earning the ire of his father when he once rolled a forklift. The factory also had a light-coloured, khaki-green Holden utility with a canopy; it was used by different sections of the company, but mainly by the maintenance shop.

Warwick learnt to drive in an old truck at the factory, Steve remembered, earning the ire of his father when he once rolled a forklift. The factory also had a light-coloured, khaki-green Holden utility with a canopy; it was used by different sections of the company, but mainly by the maintenance shop.

When Warwick was about 17 years old, Hank totally rebuilt the car, sprayed it in a different colour, and gave it to his son as a gift when the boy started at Flinders University. This was hardly the ‘new car every year’ story Brian McHenry had related to Stuart, but it showed that Hank had some affection for his son – or perhaps that he was buying Warwick off.

Stuart also asked Steve to describe Hank as he remembered him. Although Hank would have been middle-aged (in his late forties in 1966), Steve said he had a ‘babyish face’ and always looked ‘younger than his years’. He was tall, fit and tanned, with darkish blond hair, and only seemed to start ageing once he got into his fifties, when his hair turned silver and he put on a bit of weight. As he got older, Hank became ‘stooped’ – a shadow of the man who swam at Glenelg, played golf and kept himself fit.

Whenever Steve thought of new information that might be helpful, he would call Stuart from Adelaide. Steve was still in regular contact with Warwick, and Stuart was impressed by the fact that Steve was loyal to him, and wanted him to get the best help available.

Stuart spent about six months trying to dig up information about Frank Barsley – the man Bob Peters said had gone to Victor Harbor with Hank – to no avail. But as far as Stuart was concerned, the rumours about Hank weren’t rumours anymore.

According to a number of people, Hank Harrison was a paedophile, operating within a few hundred metres of Colley Reserve at the time the children went missing, completely undetected. He’d been hiding in plain sight, protected by his wealth and influence, and his family’s fear.

In Adelaide in the 1960s, that might have been enough to get away with murder.

The Satin Man by Alan Whiticker with Stuart Mullins, New Holland Publishers RRP$24.99 available from all good book retailers or online www.newhollandpublishers.com