What Abbott can learn from Keating and Hawke

In this exclusive extract from his biography of the former PM, David Day reconstructs the dramatic events that delivered Paul Keating the Prime Ministership in 1991, six months after losing a first party room vote 66 to 44. Are there lessons here for Tony Abbott, Malcolm Turnbull and the LNP government?

Paul Keating has resigned himself to never achieving his ambition. He and his supporters have spent the last six months trying to shift (Bob) Hawke supporters to his camp, but the task has proved beyond him. They might be able to count on an additional six votes, but that’s not enough. Keating requires twice that number to have a bare majority of the caucus behind him. So he decides to resign from parliament in the New Year and begins by emptying his office of personal effects, as he prepares for the shift back to Sydney. His life’s work seems at an end. Just as he’s about to abandon it all, the political atmosphere in Canberra begins to change in ways that suit him.

· LIVE BLOG: Abbott survives spill

· ‘Damaged goods’: Abbott survives leadership coup

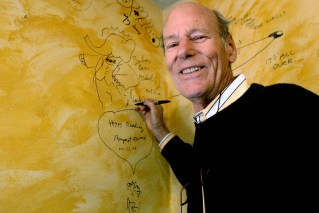

Keating with Bob and Hazel Hawke in 1988, three years before he would win his leadership battle against his boss. Photo: Getty

The increasing despair in Labor ranks is compounded on 5 December, when a flustered (John) Kerin is asked about ‘GOS’ (Gross Operating Surplus), and is forced to ask the journalists what the acronym means. It provides a stark contrast to the manner in which Keating used to toss such acronyms about with the aplomb of a circus juggler. It’s a minor slip that nonetheless is disastrous for the government. (Robert) Ray and (Graham) Richardson urge Hawke to recapture the initiative by reshuffling his ministry, bringing new faces to the fore so that the government gains sufficient political momentum to take it to the next election. Richardson later claims that he was playing a dark game in urging this on Hawke, confident that Hawke would settle for a limited reshuffle that would be derided by the media. This is certainly what occurs in the wake of Hawke’s announcement on 8 December, when the main change is to put Willis in Kerin’s place.

Rather than shoring up Hawke’s position, the minor reshuffle makes him appear weak and desperate. It’s time for Keating to strike, and Hawke is the one who provides him with the opportunity when he recalls MPs to Canberra for a one-day sitting on 19 December to pass legislation on political advertising. ‘It was a very bad move by him’, says Keating. When Leo McLeay and other supporters come to his half-empty office on the night before the sitting, they see for themselves that Keating is serious about resigning. They realise that having both Hawke and Keating is no longer an option, and they have to make a decision. Frantic lobbying takes place to get Hawke to go. Although the Left faction is showing signs of deserting Hawke, there’s no certainty that another vote on the leadership will produce the required number for Keating. So there is another attempt to pressure Hawke into going voluntarily. This time, the arguments for doing so are put to him by a delegation of his formerly close supporters — Kim Beazley, Gareth Evans, Robert Ray, Michael Duffy, Gerry Hand and Nick Bolkus — who crowd into Hawke’s office on 11 December and urge him to resign.

Annita and Paul Keating celebrate his re-election in 1993. Photo: Getty

‘Pull out, digger’, says Evans, ‘the dogs are pissing on your swag’. Once again, Hawke plays for time, even if only a few hours, promising to give them a response later that day. Richardson is certain this will mean Hawke’s resignation. Instead, Hawke tells them he will push it to a vote. In that case, they pledge him their votes, even though his prime ministership is clearly terminal. What’s more, they begin campaigning on his behalf, ostensibly to ensure that Hawke isn’t completely humiliated by the caucus vote.

With the caucus set to meet at 6.30 pm on 19 December 1991, the lobbying goes on into the early morning of that day. Whatever the caucus does, Labor looks done for. A poll published in the Bulletin on the morning of 18 December shows the Liberals with an election trouncing lead of 20 per cent over Labor, while (John) Hewson scores 80 per cent as preferred prime minister to Keating’s 12 per cent. The Bulletin ‘the recession we had to have’ poll might account for Hawke’s good humour that night as he hosts a caucus Christmas party. But there’s not much laughter the following day, when the revellers of the previous evening dump a prime minister who has led them to four election victories.

After the belated lobbying by Hawke’s supporters, the vote is a close-run thing. With three MPs absent, Keating receives 56 votes to Hawke’s 51 votes. ‘However close doesn’t matter’, says Annita (Keating), who had lost patience with Hawke years before. And she’s right. It’s an historic moment for the Labor Party, but there are no celebrations in the caucus room as MPs, some of them in tears, come to terms with what they’ve done. Although no tears are shed by Keating, he is as sober as any of them. It has been emotionally taxing to overthrow a man with whom he has worked for nine years.

The sober atmosphere is partly because everyone expects that Labor is heading for a hiding at the next election. Keating’s job is to rescue as much of the furniture as he can. Characteristically, he intends to do much more.

©DAVID DAY. THIS IS AN EDITED EXTRACT FROM PAUL KEATING: THE BIOGRAPHY by DAVID DAY.

HarperCollins Australia; hardback; rrp: $49.99; Available as an e book.