My teenager is a graffiti artist. I’m ok with that

Getty

My 17-year-old son spray paints walls and leaves his tag on buildings, and that’s ok with me.

He sometimes goes out at night to paint in public places, or leave his hand-drawn stickers on street signs, and although I struggle with it, ultimately I support him.

Am I blind to his behavior because I’m his mum? Or do I stand beside him in his implicit protest? Definitely the latter.

Street art is a fraught and divisive issue, and one that troubles the nation’s powerbrokers. Fans travel to Melbourne’s laneways, for example, to see some of the world’s best street art. Companies have been set up to offer tours to visitors and school kids.

He makes considered and thoughtful art of which he is proud. And I am proud of that.

Yet graffiti removal is a growing industry. Police will arrest you for your work, while that same work is used by the city council to attract tourists. If constructing a coherent response is confusing for lawmakers, imagine the quandary my son’s hobby puts me in.

Vandalism and art?

My son is a passionate artist who is invested in the street art culture, sees a future in that world and identifies strongly with it. He is not a disaffected youth angrily spraying his discontent across private property. He makes considered and thoughtful art of which he is proud. And I am proud of that.

Yet many people see any form of unsanctioned urban art as vandalism. They argue that it’s an eyesore that should not be forced upon them.

Fair enough, but what about the ugly, sexualised, often mysognist advertising that fills our urban spaces? The huge, leering billboards that exhort men to get it up and go for longer, the fast food being pushed at our kids, or women reduced to just so many body parts – thrusting breasts, pouting lips or spread legs selling everything from men’s shoes to alcohol?

I’d much rather see street art than any of this visual pollution.

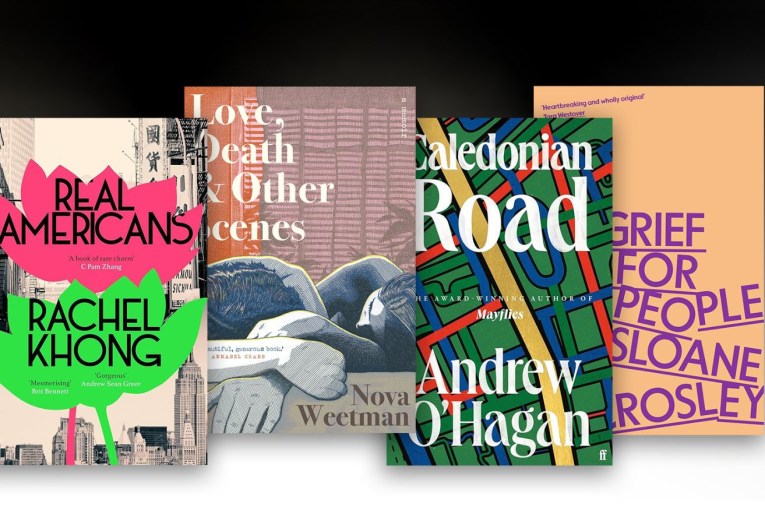

Gallery assistants adjust ‘Love is in the Air’ by British graffiti artist Banksy. Photo: Getty

Words from the master of the form

In his book Cut it Out, famed street artist Banksy writes of advertising:

“They leer at you from tall buildings and make you feel small. They make flippant comments from buses that imply you’re not sexy enough and that all the fun is happening somewhere else … They are The Advertisers and they are laughing at you.

“Any advert in a public space that gives you no choice whether you see it or not is yours. It’s yours to take, re-arrange and re-use. You can do whatever you like with it. Asking for permission is like asking to keep a rock someone just threw at your head.”

Street art makes some people very angry. But I wonder if that is not the point of art? To provoke a response?

When the French Impressionists first began creating work they were barred from taking part in mainstream art events. Their work was derided and ignored. Back when Banksy was just another tagger he snuck his work into the Tate Modern Gallery in London. When it was discovered the canvas was dumped in the lost property department. Today a Banksy original can sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars and the artist’s personal worth has been estimated at about $22m. Not that this brings Banksy much joy.

“Commercial success is a mark of failure for a graffiti artist,” he said in a recent interview.

A finely drawn line

The line between valuable art and scribble is a changeable thing. Mostly we wait for an authoritative voice to tell us what has value and what should be ignored.

My son dislikes the glamourisation of street art, and the attempts to own and control the culture by authorities who will cash in on one hand – offering local street art up as a tourist attraction – and control on the other – pursuing and prosecuting street artists.

Good street art he tells me, is about subversiveness, about challenging the status quo and forcing people to question mainstream ideas. It should be raw, edgy and push boundaries.

The issue many will raise at this point is where street art appears – in places the artists do not have permission to paint. This points to the clear negatives: graffiti removal costs about $200m a year in Australia and in 2011 an 18-year-old youth died after being hit by a train while tagging in a Sydney railway underpass. State police forces assemble graffiti task forces to combat the problem and compile a database of regular tags. It’s a dangerous passion.

But I wonder if he would be in more danger if he were sitting at home, digesting a homogenised diet of bland television consumerism, updating his Facebook status with inanities, and only using his brain to track down the bad guys on the latest video game?

Where side of this debate do you fall on? Lock them up or let them loose? Leave you thoughts in the comments field below.

Grace Sanderson is a pseudonym used by the author to protect the identity of her son.