How Indigenous workers got the money they were owed

Mervyn Street, the lead plaintiff on the historic case, pictured after the verdict. Photo: AAP

It was an apology that was a long time coming, but worth the wait for the hundreds of people affected.

On Tuesday, the Western Australian Premier Roger Cook apologised in Parliament for the hardship and exploitation of past legislation that essentially robbed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers of pay for decades.

“Aboriginal men, women, and children worked hard and made enormous contributions to the economic development of this state, but they received only a fraction of their worth,” Cook told Parliament.

“An apology does not change what happened. It cannot, but it recognises the importance an apology has as recognition as a move towards reconciliation and a step in a healing process in bringing a close to this shameful part of Western Australia’s history.

“On behalf of the state of Western Australia, I apologise to the Aboriginal men, women and children who worked in Western Australia between 1936 and 1972, often for decades for no pay or not enough pay. We acknowledge that many of these people have not lived to see this day for their family members who remain. We are sorry for the hurt and loss that your loved ones suffered …

“To you all, we say, sorry.”

Watching this apology, with tears in his eyes, was a barrister from the bush town of Mount Isa, who has travelled around Western Australia’s most remote outposts for six years, gathering stories of those whose backbreaking labour was exploited.

An equally important aspect of this settlement for barrister and proud Waanyi and Kalkadoon man Joshua Creamer, is finally validating the truth about this chapter of Australia’s history.

“Life is made up of moments and it was a very special moment,” Creamer said.

“Honestly, I think these cases are all about truth-telling.

“I realised this cohort of Aboriginal people over the age of 80 are few and far between, and those stories won’t be around in another decade or so. So to be able to give those stories some life and to educate the public and hopefully create a better understanding of our history … is an important part of these cases.”

The apology came days after a significant class action judgement, when the Western Australian government agreed to pay $180 million to thousands of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders whose wages were withheld while working on outback stations between the 1930s and 1970s.

Mervyn Street and WA Aboriginal Affairs Minister Tony Buti. Photo: AAP

State government policy at the time allowed the government to hold up to 75 per cent of an Aboriginal person’s wage.

Creamer travelled thousands of kilometres to bring people’s stories to court, and ensure justice prevailed.

“There’s not much of the Territory and WA I haven’t seen. I’ve spent a lot of time up there and I have a huge amount of respect for the people,” Creamer said.

“What you have to remember in these types of cases is people are often telling you the stories about the toughest part of their lives, not just the work, but sometimes the brutality and the abuse that women suffered at the hands of station owners.

“And I know that they have often never told their story, not even their family members will know all these things. So it’s a real privilege to actually be part of that.

“I call them the forgotten Australians because they’ve been swept aside and their contributions forgotten about, but hopefully we can shed some light on that.”

Barrister Joshua Creamer. Photo: Supplied

Four years before this successful case, the Waanyi and Kalkadoon man was also acting as a barrister in the Queensland stolen wages class action, that settled for a similar amount ($190 million).

“We really dig deep into the history of this country and we try and bring that to the surface. It’s an important part and hopefully these stories get told and get known,” he said.

Considering that research shows less than 10 per cent of class actions reach a successful post-trial outcome, it’s an impressive success rate. But Creamer is all too aware it cannot possibly make up for the intergenerational wealth and prosperity that was deliberately kept from them.

After hearing about so much heartbreak, he is thrilled that the work of so many First Nations people is finally being recognised.

“In Queensland, people worked often for private employers and their wages were paid directly to the government and the government held onto those wages. In Western Australia, it’s a very different system. People just weren’t getting paid right up until the mid-’50s,” he said.

Now thousands of West Australian workers like stockmen, domestic servants and railway workers who had their wages stolen have a year to register with Shine Lawyers to hopefully become part of the settlement.

Their spouses and children can also claim compensation.

If the settlement is approved, the Federal Court will determine how it’s distributed, and the final amount given to each family.

“Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people working in Western Australia between the 1930s and up to 1973, working on cattle stations in the Kimberley region, Torres Strait Islanders working on the railways, women working as domestics across WA all will be entitled to compensation,” Creamer said.

Many people to this day still have no idea that Torres Strait Islanders worked in outback WA, he said.

“In the Pilbara they had the track-laying record in the 1960s. They were so proficient at it. But coincidentally, I had a call from a Torres Strait Islander man a few days ago and asking if he was eligible, and I said ‘you are’.”

This sense of social justice that flows through much of his work was passed down from his mother Sandra Creamer.

“My mother’s a Leon, and it’s a really big family. In her time up in Mount Isa, she was the youngest of 12,” he said.

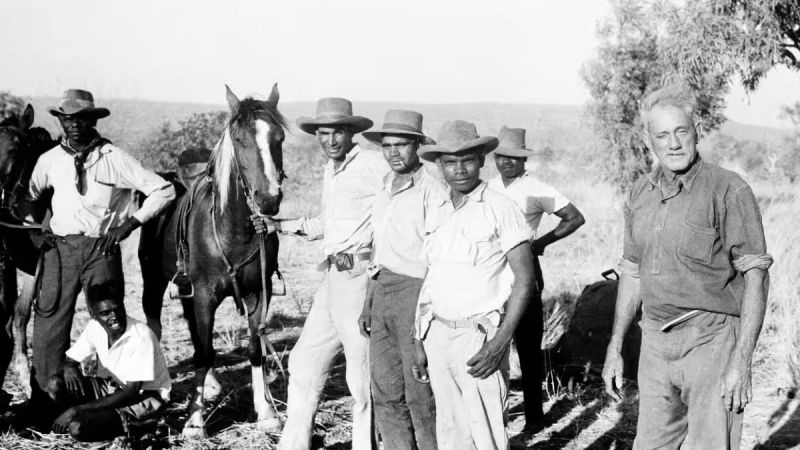

Aboriginal stockmen on a cattle station in Wyndham, Western Australia, in 1949. Photo: National Archives of Australia.

“She’s really well known now in terms of the work that she’s done nationally and internationally, particularly around Indigenous rights and human rights. She’s been well recognised at the UN level now for probably two decades.

“Growing up as a single mum, she certainly instilled in us strong values around right and wrong and the desire to actually do something for the community and Indigenous issues and social justice issues.

“So even having discussions about key issues or those types of things when you are young teenager, are things that stayed with me and it’s something I try and instil in my children.”

It all seems a world away from the butcher’s apprenticeship he started in Yeppoon, unsure of what options he had after high school. But then he realised that was just one chapter in his life, starting at Mount Isa, then moving to Queensland’s central coast with his family, and then realising his calling by studying law at Griffith University in Brisbane.

“It’s a journey. And those three parts of my life have, I think, exposed me to a whole range of things. And it’s something I think about being a father now. My kids haven’t been exposed to a lot of things outside inner city Brisbane,” Creamer said.

“I’m keen to talk to them and take them up to places and meet people. Often I come back and it’s actually hard to reconcile what I see – people living in sheds or under tarps in the Kimberleys or parts of the Northern Territory.

“I come back and I think, wow, are we living in the same time, when we can tolerate people living under those conditions and people who’ve worked for decades and are out there, being forgotten?”

With a sense of handing on the baton, Joshua Creamer and his wife of 20 years Kara Cook started a scholarship a couple of years ago to support female Indigenous law students at Griffith University.

“Hopefully those people that come through, the Indigenous lawyers coming through will go out and achieve great successes, much greater than the things I’ve done.”