Five brilliant ideas Netflix used to conquer the world

Screenshot

Netflix – the subscription TV service that launched in Australia this year – is a juggernaut. It drags people in and captures them. And they love it.

Binge-watching TV shows is not just a national pastime. It’s global. The stock price of Netflix shows the incredible extent of the company’s success.

If you’d put $1000 into Netflix in 2003, you’d have $115,000 now. In just one day last week its stock rose 18 per cent as the company revealed more new users than expected.

• Surfer Fanning’s incredible shark attack escape

• Netflix hacks: get the most out of your streaming

• Membership jumps for Netflix

• The Netflix Original movies to get excited about

How did they do it? What’s the secret to turning the globe into zombies who spend all their spare time consuming your product?

The answer is shamelessly appropriating good ideas.

Netflix has swiped the world’s sharpest and most effective business models – some well-known, some well-hidden – and combined them into one unstoppable force.

Netflix owes a debt to big oil, all you can eat buffets, airlines, Microsoft and casinos.

The oil industry perfected the concept of owning the whole supply chain

Think about Shell. It owns everything it needs to do business – from exploration activities that discover where the oil is, to drilling machinery, to the service station where you fill up your car.

When Netflix decided it was going to spend $100 million to hire Kevin Spacey and make House of Cards, it was thinking like an oil company.

When Netflix decided it was going to spend $100 million to hire Kevin Spacey and make House of Cards, it was thinking like an oil company.

Owning the whole supply chain is known as vertical integration and it gives a company power. Oil companies do it to control price, quality and quantity.

Don’t just own the distribution mechanism, because that makes you vulnerable. Own what you’re selling too. Netflix’s most famous house-made products are House of Cards and Orange Is the New Black, both of which have proven to be black gold. It has dozens more.

The risk for Netflix is a hit show gets made and someone else wants it. For example, Amazon.com got exclusive rights to Downton Abbey by paying up big. The makers of a hit show can charge a fortune for the rights. By making its own shows, Netflix can’t be held to ransom.

Instead, when it owns content we’re dying to watch, it holds us to ransom. When you call the shots you can raise the prices, which Netflix this week announced it would do.

All-you-can eat buffets perfected the idea of eliminating transaction costs

In a normal restaurant, you pay only for what you eat. But you do pay for everything. Market economics at its purest.

Netflix has boomed thanks to the production of TV shows like House of Cards. Photo: Netflix

We weigh up the value of every choice and get a bill that lists each item. That mental and administrative effort are part of what economists call transaction costs.

Buffets, though, are like an anti-market. Once you’ve paid, it’s a wonderland where the rules of economics don’t apply. Want more lasagne? Go for it!

Humans love buffets. It’s no surprise Netflix acts like a buffet. Who wants to pay every time they click on something? Who wants to weigh up the value of letting the kids watch yet another episode of The Wiggles.

Of course, real-world buffets have a problem – if lots of hungry people or lots of fat people show up, they can go broke. To manage this they cut quality and try to entice people into eating bread and potatoes. It’s a fine balancing act.

Netflix, has no such problems. It generally costs them no more whether you watch Seinfeld repeats once or a thousand times. That’s why they are happy to let you binge for hours.

Microsoft perfected the art of bundling

Microsoft doesn’t care that you never want to make a slide-show. When you buy Microsoft Office, you get PowerPoint whether you like it or not.

This is bundling. You get some stuff you want bundled in with some stuff you don’t want. Companies do it because it lets them make more profit.

The idea is simple. Imagine I would pay a maximum of $10 for product A and $6 for product B. Your preferences are the other way round.

If the company tries to charge $10 for product A and $1 for product B we each buy just one thing. The company makes $20.

If the company wants to sell two of product A and two of Product B, it must set the price for each at $6. It can makes $24. Better, but not the best.

If it bundles the products into A+B packages costing $16 each, it can sell all four items and make $32! This is their best option.

When you buy Netflix you get a lot of stuff you’ll never watch. Maybe horror films, or BBC murder mysteries. That’s the Microsoft PowerPoint part of the bundle.

Airlines perfected the art of price discrimination

When you go to the Netflix website, you face a decision. Pay $8.99, $11.99 or $14.99.

Orange Is the New Black has been credited with drawing hundreds of thousands of new subscribers.

No matter how much you pay, you get access to all the same shows. The difference is in whether the content is delivered in regular definition, high definition, or ultra high definition, and how many screens the content can be viewed on.

This is what experts call price discrimination. Airlines do it best.

Whether they sell you an economy ticket for $700, a business class seat for $2000 or a first-class experience for $5000, you all take off and land at the same time.

Charging people different amounts for the same basic thing works well because of a concept called “willingness to pay”. Not everyone will pay the same amount for the same goods.

If a business sets just one price, it misses out on profit. There are some people who would pay more than that. Even more important, there are people who would be profitable customers if the price was just a bit lower. Different prices for different folks is a proven model.

Netflix wants to skim their first-class passengers for as much as possible, but also fill up the back-end of the plane. The great thing for them is their plane has an unlimited number of seats.

Expect even more pricing levels to arrive in future.

Casinos perfected the art of keeping us hooked

The flashing lights on a poker machine are scientifically designed to provoke the reward centres in our brain. Like rats in a cage we get addicted on the dizzying sequence of highs and lows, pay-offs and disappointments.

Just one more spin, says the poker machine addict.

Just one more episode, says the Netflix addict.

Scientists have shown a good film or a good show controls our brain. A director makes a character act in a certain way and cuts the scene. The brains of viewers all release neuro-transmitters on cue. (The same is not true of a bad film.)

With free-to-air TV there was nothing we could do except wait a week to watch the next episode. But with Netflix the next episode is right there, ready and waiting to deliver more brain stimulation.

Throw it all together and you get market domination

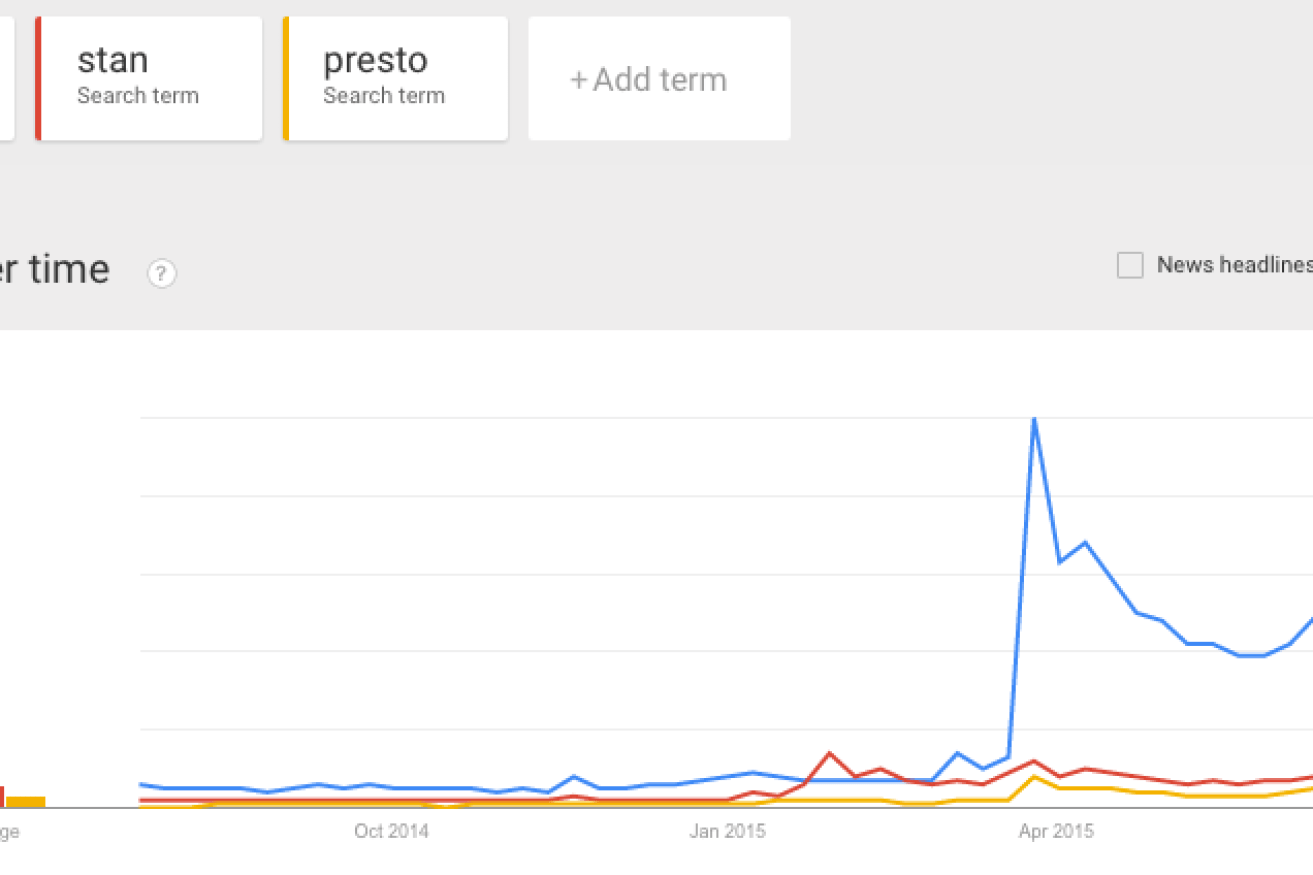

Its hard to believe Netflix has only been in Australia for a few months. Its devotees are already wild-eyed with fervour and Google Trends data shows it blowing rivals Stan and Presto out of the water.

Screenshot

Netflix has nearly doubled its subscriber base outside America from 12.9 million to 21.6 million, in just the past 12 months. And it plans to launch in Japan very soon.

The executive at Blockbuster who passed up the option to buy Netflix for $50 million over a decade ago is probably feeling very sheepish.