The other day a young couple bought a nice three-bedroom house in Brady Road, Bentleigh East, 23 kilometres from Melbourne’s CBD, for $1,263,000.

I don’t know what their deposit was, but if it was 20 per cent, they borrowed a million dollars. Repayments: $6576 per month.

But here’s the reality of what has happened to housing affordability in Australia: If the overall house price to income ratio in Australia had stayed what it was in 2000, and what it had been for decades before that – that is, four instead of the current eight – that family would have paid half the price they did, and their repayments would be $3293 per month.

But because house prices have been rising at roughly twice the rate of incomes over the past 25 years, they had to pay twice the equivalent of what their parents paid for a home, and fork out more than $3000 extra per month to the bank.

At a national level, ABS data shows that quarterly housing loan interest paid to the banks has gone from $9.9 billion, or 3.7 per cent of total disposable income, in 2004 to $31.8 billion, or 6.7 per cent of disposable income in December 2023.

Banks reaping profits

If housing interest had stayed at 3.7 per cent of disposable income because the house price to income ratio had stayed the same, it would be $17.7 billion per quarter, or $14.1 billion less than it is.

That’s an extra $4.7 billion per month going to the banks, and out of the pockets of Australian households and the other businesses where they would be spending it. This is the cost-of-living crisis.

And, of course, it’s also why the banks are making so much money and the executives are being paid so much.

That’s the banal evil of housing affordability that was highlighted for the umpteenth time last week by the new National Housing Supply and Affordability Council (NHSAC) appointed in January to solve the problem.

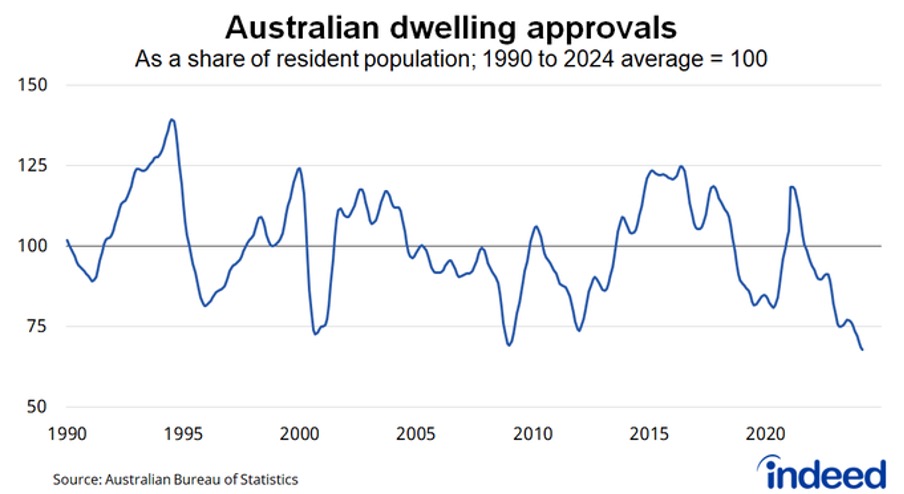

Its first report on Friday investigated and exposed the problem, provided no solutions, and predicted it will get worse, which was supported by new building approvals data the day before showing that approvals as a share of population are now the lowest in history, or at least for several decades.

The council, headed by the former CEO of Mirvac, Susan Lloyd Hurwitz, concluded that: “(Our) projections indicate that new market supply will fall short of new demand over the next six years.”

It was a dismal report full of dismal graphs and numbers. These are the key ones: “over the council’s full six-year projection horizon, net new market housing supply is expected to total 1,040,000 dwellings. New demand is expected to total 1,079,000 households. This represents a deficit of new market supply relative to new demand of around 39,000 dwellings over the six-year period.”

Off target

The National Housing Accord between the Commonwealth and the states was launched in a blaze of press releases in 2022 with a target of 1 million homes over five years starting on July 1 this year – that is, leaving out the current financial year, on which more later.

That target was raised last year to 1.2 million. By the way, the NHSAC was created as part of that accord to show they were serious.

The council also did a five-year supply forecast starting on July 1 to match the accord time frame and came up with 903,056 – an absurdly precise figure.

It’s 296,944 less than the round number of the National Housing Accord target, and that shortfall naturally headlined all the news reports about the report, as it knew it would.

That forecast turns into net new supply (after demolitions, presumably) of 869,126 over those five years versus demand during the same period of 871,022 – two more absurdly precise numbers. That’s a real shortfall of 1897 which, you’d have to say, is close enough to be a market in balance, since these are just numbers plucked from a Treasury spreadsheet, and even Treasury would admit that its spreadsheets are not precise when it comes to the future.

Timely projections

But there’s a reason the National Housing Accord starts on July 1 this year and not last year or the year before when the ministers actually met: The projected shortfall over the council’s full six-year time frame is 39,176 – 95 per cent of which is in the current financial year because of this year’s immigration surge, which has been entirely unmatched by new housing supply, which has in fact been falling, as the latest approvals data showed.

You have to feel a bit sorry for the Minister for Housing (and homelessness and small business) Julie Collins, who had to front up and release a report that calls out her government’s failure while having nothing new to say on the subject.

So she firmly repeated the ambitious targets (“We need to be ambitious”, she intoned, straight-faced), as if the report she was releasing didn’t blow up the targets.

But she did her job stoutly and repeated the targets and dollars previously announced, before retreating to her office to prepare a happier press release about helping small businesses deal with cyber threats.

No easy solutions

Does anyone have a solution for the $4.7 billion per month being siphoned to the banks, identified at the start of this column, beyond announcing supply targets that won’t be met? No, not one that’s likely to be implemented.

It’s too late to deal with the demand surge from immigration because it has already happened, and will take years to work through.

And no one wants to tackle negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount, and in any case, investors who use those tax concessions are deserting the housing market right now because even with them and sky-high rents the returns from capital gains are unlikely to be good enough because anyone can see house prices can’t rise any more. Can they?

Thousands of houses are sitting empty because the cost of renovating them to be rented out is too high to be a good investment – you’re better off buying Commonwealth Bank shares and collecting the 4 per cent fully franked yield.

As for the supply of new housing, governments can have all the accords and targets they want, but they don’t build houses, or at least not many, developers and builders do, and building houses is a terrible business.

Building dilemma

That’s because the cost of building has gone through the roof, state governments, especially Victoria, tax new housing like the feds tax luxury cars, and also because builders are over-regulated, unprotected and marginal businesses.

You’d have to be crazy to be a builder. The state government building authority is all over you like a rash, the insurance is prohibitive, you have to commit to a fixed end price for a product that will take a year to make during which you have no control over input prices and, meanwhile, your customer is trying to screw you because they are desperate as well.

But there’s nothing new about that: My dad was a builder and he went bankrupt twice, although there were a couple of good years when we owned a Valiant and a boat.

So a good start for Julie Collins in meeting her targets would be to put on her small business hat and start protecting builders and developers from the predations of state governments, so there’s more of them.

Alan Kohler writes weekly for The New Daily. He is finance presenter on the ABC News and also writes for Intelligent Investor