‘The day my dream run ended’: political journalist Shaun Carney

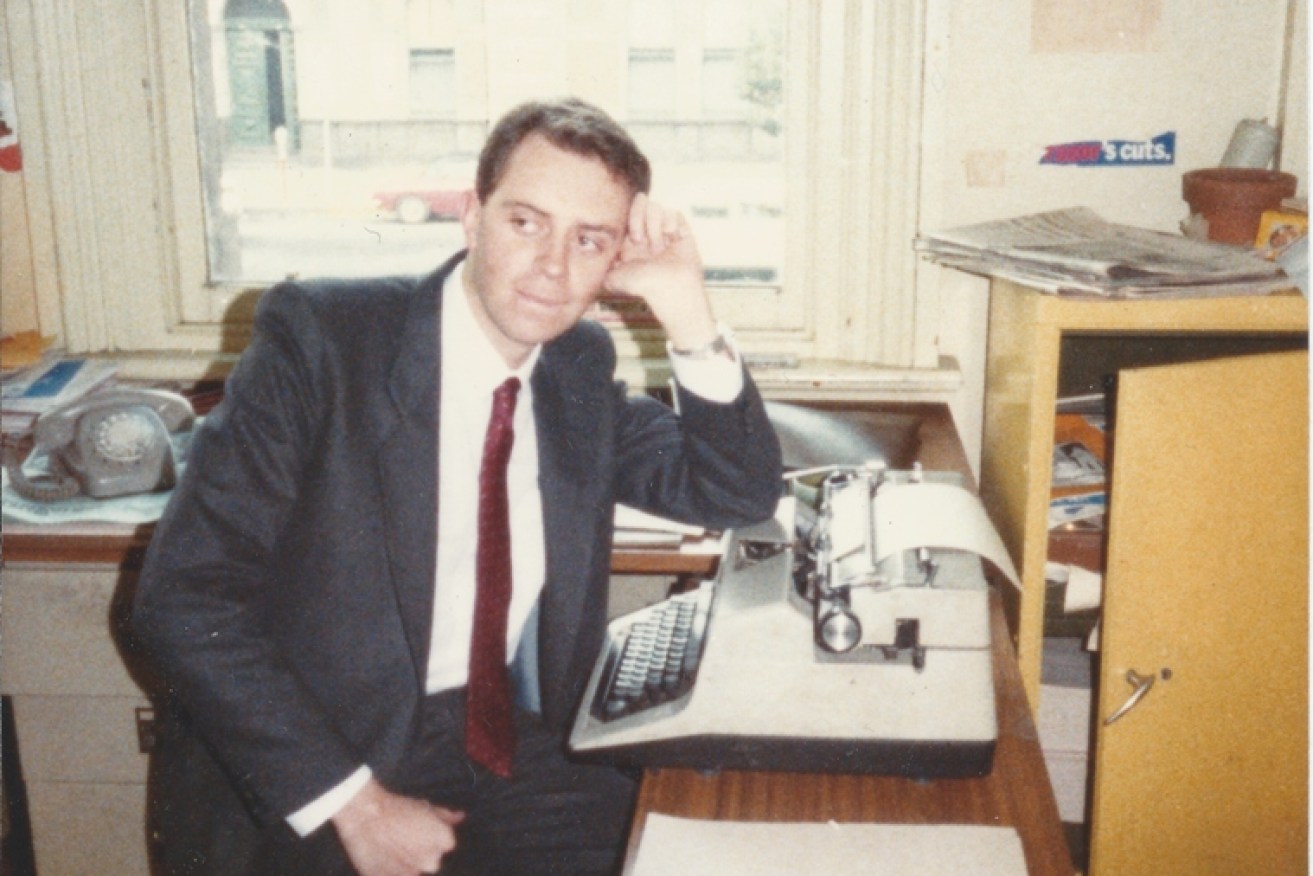

Political journalist Shaun Carney (in 1984) took a redundancy at Fairfax and stepped into an uncertain future.

Political journalist Shaun Carney’s glittering newspaper career ended as it began – with a brief phone call. Here, in an extract from his memoir, he recalls the day he joined the ranks of redundant workers – and began a new life.

The date for the latest wave of voluntary redundancies set by Fairfax Media, owner of The Age, was only three days away.

I was not really in much doubt about getting a positive response to my request for a redundancy. I had recently turned fifty-five, which in many modern Australian workplaces— especially those that see digital technology as the giver of light—is the professional equivalent of being in palliative care.

I’d been what passed for a ‘name’ on the paper for probably more than twenty years and I was well-remunerated compared with most of my colleagues (naturally, like every other member of the Australian workforce, though, I was sure that I was not and never had been paid enough).

But I had for some time felt that I could not figure in The Age’s future—I barely related to its present—and I’d been subjected to enough casual indifference at work in recent years to conclude that my bosses had come to the same view. If I had not got out a red Sharpie and painted a big red circle on my forehead by applying for redundancy, the bean counters and swagger merchants at head office in Sydney would have eventually done it and shot me anyway.

All the same, until you get the okay, you can’t be certain. The call from the executive editor of The Age, Rod Wiedermann, on August 28, 2012, was designed to put my mind at ease. His reason for calling was personal, not professional. “This isn’t an official call, Shaun, but I just wanted to let you know that your redundancy is going through. You’re going to be told officially tomorrow and that’s when you’ll get the paperwork. Probably best to keep this to yourself until then.”

Weeks earlier, I’d visited his office just to talk about the redundancy process and when I told him I had twenty-six years’ service and we both did the rough calculation of my likely payout, he gasped, smiled and exclaimed: “F***!”.

The task of trying to make the numbers work at The Age while also watching a succession of managers and editors passing through, all with their ideas about how to turn things around or make a difference, had given him the sort of wry humility that’s not always available in the jazzed-up, ego-fuelled environs of an editorial floor.

On the phone I thanked him for letting me know and for helping to steer my redundancy through. I knew that I had to escape that place, that life. I felt calm. I also sensed a weight pushing down, right through my body. This was my life’s work that I was abandoning. The dream had been realised, the hoped-for life had been lived—to an extent, anyway—and I had elected not to experience another moment of it.

Carney’s Victorian Parliament ID.

Rod had one more thing to tell me and his tone was mildly apologetic. “They want you out at the close of business on Friday. You’ll have three days to tidy up. Can you manage that?”

Yes, I can fit in with that, Rod, I replied.

There was a parallel process at The Sydney Morning Herald, where eighty journalists took up voluntary redundancy. Later, reports emerged of high emotion among some of the veteran reporters—of hardened, middle-aged men, some of whom I knew well, weeping together in the lifts as their roles in this great institution came to an end.

There was none of that in Melbourne, or at least not that I saw or ever heard about. I certainly couldn’t get choked up. My unsentimental reaction wasn’t driven overwhelmingly by the money or the way the job and the company had changed in the face of evolving digital technologies, although they did have something to do with it. I just needed to get away and this was my best and least painful chance to do it.

Every year, tens of thousands of Australians find their lives disrupted and diverted—and, in many cases, irreparably damaged or diminished—by redundancy. Australia Post shrinks, a hardware chain collapses, an electronics retailer falls over, call-centre work is shifted from a regional centre to India or the Philippines, a smelter shuts down, a nickel refinery closes, and the media refers to the workers who are being turfed out as numbers: 190 at one place; 230 at another; 3000 over there. Generally, these decisions to divest employees are reported once and the news cycle moves on.

Carney and his parents at his graduation.

In 2006, I attended a talk by Bill Clinton at a function room in the football stadium in Melbourne’s Docklands. At one point in his free-ranging discussion of the state of the world, he chided the businesspeople who’d paid up to $2500 to attend, questioning their ability to understand what went on around them.

The audience was seated at round tables. You’re all sitting at those tables, Clinton said. How do you think those tables got there? Who laid out the tablecloths? Who put the chairs around the tables for you to sit on? Someone did all those things so you could be here.

After you leave, they’ll come back and take away those tablecloths and pack up the chairs and tables. And every one of those people who did that for you has a life, a home, people they love, hopes and aspirations. They’ve all got a story. Do you ever stop to think about those people when you come to a place like this? You should, he said.

I really didn’t know what I’d be doing after The Age, although I’d been thinking about it a lot. While I cared about that—naturally, I cared because I had family responsibilities and I would have to find a way to keep making a living—I couldn’t see how I could go on with my working life as it was currently arranged, not with what I’d seen and experienced in recent years.

Fear and lies shape so much of human behaviour. They definitely played a big role in my life. They got me into journalism. But I’d been scared of stepping out of line, of standing alone and relying on myself, for as long as I could remember. Now I would find out if I could do it.